THIS TOO, IS A MAP rejects hollow artworld messaging and orients itself towards different modes of encountering and representing the world

The notion that cartography is inseparable from the desire to possess, control and exploit land (often other people’s) has become almost a truism in contemporary art. Recent years have seen no shortage of ‘urgent’ exhibitions addressing the politics of mapping, migration and globalised resource extraction, even as the same inequities in wealth and power that are condemned in such exercises remain baked into the artworld. Rachael Rakes, artistic director of the 12th Seoul Mediacity Biennale (SMB12), titled THIS TOO, IS A MAP, writes frankly in the exhibition’s companion anthology about the cynicism surrounding the hollow ‘save the world’ messaging that has ‘become innate to contemporary art practice, which is always stuck in a loop of self-valorization for itself to continue, or at least stay contemporary’. Resisting this impulse, Rakes and associate curator Sofía Dourron have instead oriented SMB12 towards different modes of encountering and representing the world.

At the Seoul Museum of Art’s (SeMA) Seosomun building – the largest of the biennale’s six venues – Agustina Woodgate’s installation The New Times Atlas of the World (2023) employs a custom machine-learning program to regenerate outdated maps the artist has sanded down into blurry, pastel-hued land masses. With each turn of the page by an automated flipper, the system projects a reconstituted image onto an adjacent screen. The work goes beyond the usual gimmickry of AI art to visualise constructed terrains while echoing, in its use of an obsolete atlas, the problem of machine learning’s reliance on existing sources of information, with all their errors and biases. A compellingly low-tech subversion of territorial representation is Anna Bella Geiger’s black-and-white film series Mapas elementares (1976), produced 12 years into a military dictatorship in the artist’s native Brazil. In one clip, Geiger is shown colouring in a map of the country with a black marker, accompanied by a deceptively cheerful-sounding song by Chico Buarque that relates how, despite the football and samba, “things here are pretty nasty”. In another film, she traces similarly shaped outlines of South America, an amuleto (amulet), a mulata (the mulatto woman) and a muleta (the crutch), alluding to arbitrary demarcations of land as well as loaded signifiers of culture, race and class.

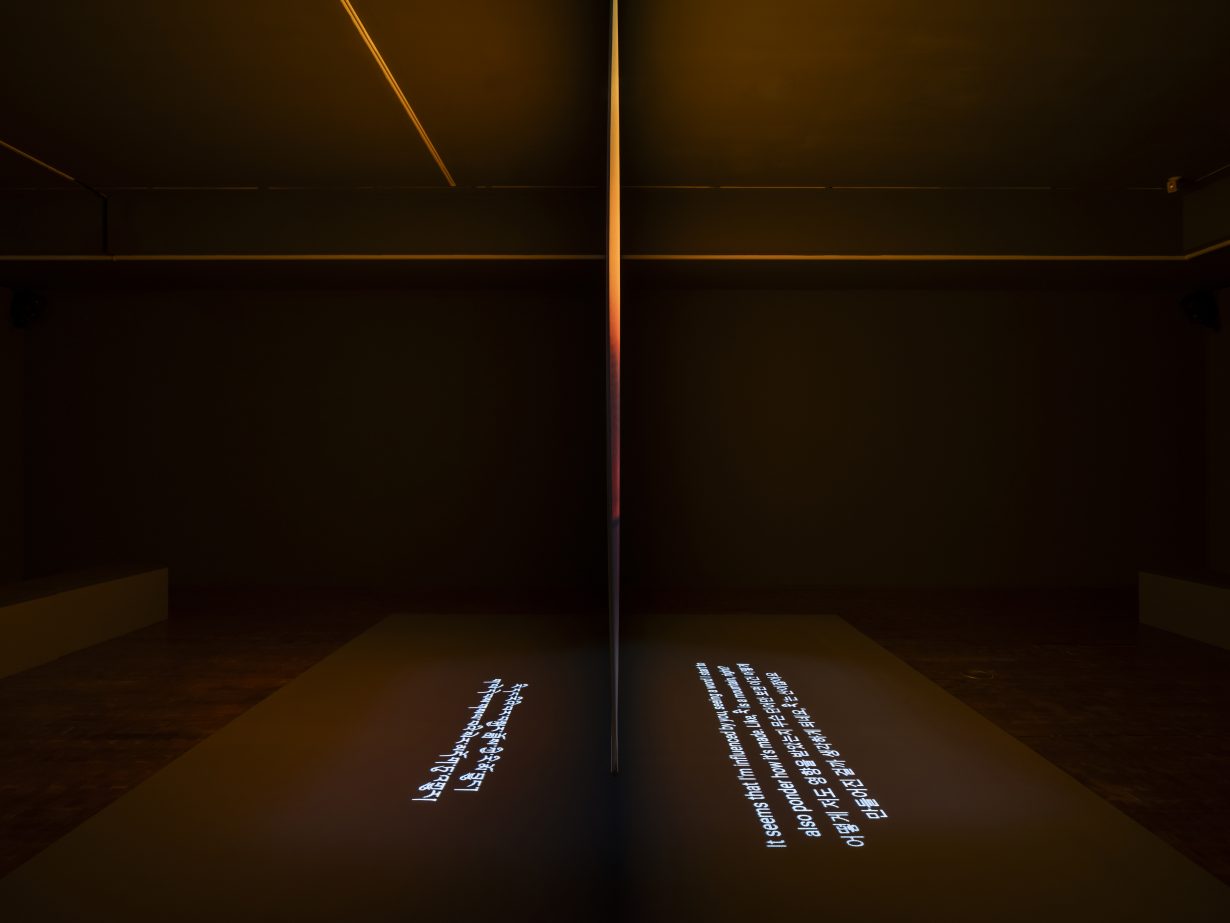

The exhibition frequently contends with the limitations of language in expressing our experiences of the world, as exemplified by Shen Xin’s atmospheric installation ས་གཞི་སྔོན་པོ་འགྱུར། (The Earth Turned Green) (2022). Displayed in a darkened room, a double-sided projection captures the changing light inside a bare studio, from amber ripples to Rothkoesque fields of blue and vermilion. In the accompanying audio recording, the artist converses in Mandarin with a Tibetan-language teacher about ways to describe various colours and natural phenomena, with subtitles in Korean, English and Tibetan projected onto the floor. As we learn how the Tibetan word for fog can also refer to clotted blood, and how the verb ‘to flourish’ is connected with fire, we are reminded of how our relationship with nature is at once close and alienated – after all, the vibrant lightshow onscreen is artificial. Christine Howard Sandoval attempts to bridge this distance in Surface of Emergence (diptych) (2023), rendering Spanish Colonial-style arches in adobe to interrogate the material and aesthetic legacies of conquest.

Extractivism is the focus at SeMA Bunker, where Femke Herregraven’s two videos on mining in Africa stand out. I See What You Don’t See (2019) features aerial footage of rocky terrain as a woman lists valuable minerals and metals in a hypnagogic whisper. Nearby, Prelude to: When the Dust Unsettles (2022–23) splices exploratory drone footage and 3D simulations of detonation sequences to demonstrate how advanced imaging technologies are being used to develop lithium mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. These abstracted images are further distorted by the peaks and troughs of the terrain model onto which the video is projected.

An intriguing question that recurs throughout the exhibition is whether a given place – or the standards and modes of its representation – can be thought of as real. This is accentuated in works that engage with diasporic reimaginings of home. In Tenzin Phuntsog’s film Pure Land (2022), shown at SeMA Seosomun, a photographer drives across Montana in search of a location that resembles his mother’s native Tibet, leaving voicemails to ask about the colour of the Himalayas in spring and the cold earth in winter. Shot on Blackfeet tribal lands, Phuntsog’s poignant film enacts a futile substitution that gestures to shared histories of exile and dispossession.

The entire SMB12 venue at the Seoul Museum of History was devoted to Jesse Chun’s practice on dislocation and untranslatability, including a new series of large-format paper works adorned with gradient patterns of horizontal graphite lines and cutout shapes derived from Korean and English graphemes (시:concrete poem, 2023). These abstract compositions of textual fragments complement Chun’s three-channel video installation O dust (2022), in which superimposed imagery of waves, a full moon and empty conference rooms at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris disappear and reappear on screens and floor-based mirrors to the sound of overlapping utterances such as “oh” and “sh” along with phrases in French, English and Korean. Rife with ruptures and interpolations, Chun’s works reveal the constant negotiations of linguistic hierarchy, belonging and memory that inflect the diasporic experience.

SMB12 is low on spectacle, and the projects that best encapsulate the exhibition’s ideas tend to be understated and contemplative. At times, the biennale can feel constrained and repetitive, retreading rather than transcending familiar formal and conceptual boundaries, but it attests to an assured curatorial hand and rewards the patient viewer.

12th Seoul Mediacity Biennale, Various venues, Seoul, 21 September – 19 November