In passing the fugitive on, the viewer is invited to think about almost everywhere but Gaza

Thirteen, unlucky for some. Like, one might say, Zasha Colah, Mumbai born curator of the 13th Berlin Biennale, the first such event since the cataclysm began in Palestine. While Colah here presents a politicised biennale, the German state’s position on criticism of Israel (verboten, basically, though even Federal Chancellor Friedrich Merz broke protocol on this shortly before the show opened) effectively means that German art institutions are deafeningly, horrifically silent on the matter, and so it is here. That’s ironic, since a leitmotif of this biennale – titled passing the fugitive on – is the fox, wilily slinking its way through urban space, defiantly going where it wants; and the exhibition is avowedly predicated on ideas of inventively enacted resistance through agile ephemerality, fugitivity, humour, poetry. Given that Colah hasn’t, unlike some other art practitioners, elected to boycott Germany’s compromised public art spaces altogether, you’re left wondering whether another stricture might have been resisted here, somewhere amid these 60 artists and 170-plus works? In the end, you’re left with a sense of a fox with its feet tied.

Instead, a viewer is invited to think about almost everywhere but Gaza, particularly the ‘Global South’, and, additionally, to consider the value of symbolic dissents. Early on at one of the four venues, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, we encounter Han Bing & Kashmiri Cabbage Walker’s props for a long-running absurdist performance, in which a person in traditional Kashmiri dress pulls along a cabbage, basic item of rural sustenance, on a little cart. This work, originally made to protest the massive military presence in Kashmir amid the India/Pakistan conflict, is, says the catalogue, ‘a mischievous signal to the potential of radical actions, which in their silence and wit can be extremely loud’. Soon after, a volunteer might ask if you want to play Panties for Peace (2007–21), an online videogame associated with the eponymous Myanmar activist group, in which you fire women’s underwear at a South Park-ish caricature of the country’s Than Shwe, because ‘Brutal Burmese dictators believe contact with women’s underwear will sap their powers’. Soon after that, there’s El Corpiño (1995), a giant anti-patriarchy bra made by an Argentinian women’s collective led by Cristina ‘Kikí’ Roca, from which dangles a label reading (in Spanish) ‘No chest can bear it anymore’.

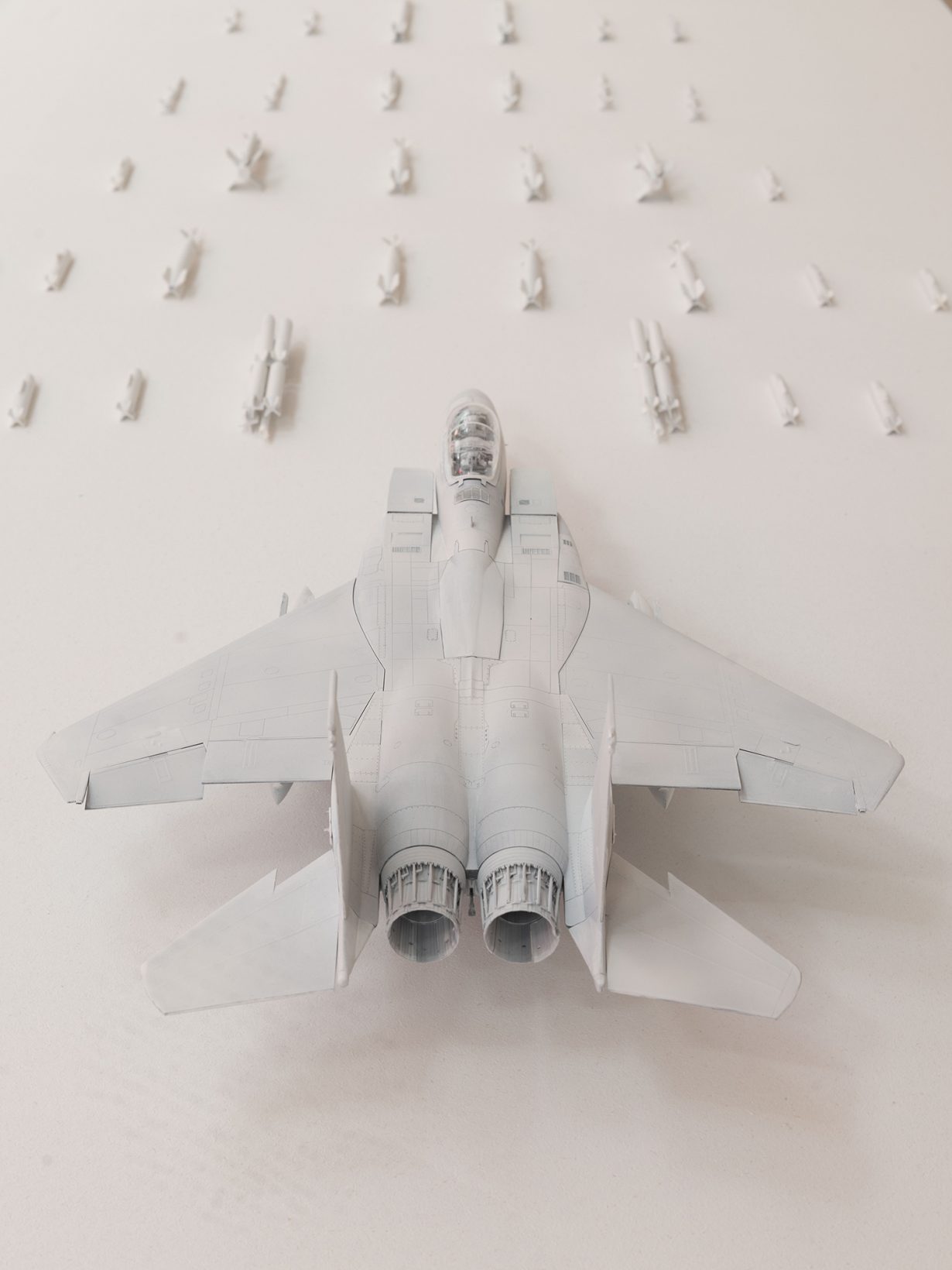

There’s a lot of this at KW: art that looks like it would be equally at home as part of a march, like Piero Gilardi’s oversize carnivalesque puppets – including, in Trump’s mill (2017), perhaps the chief puppet of our time. There are also extraordinary acts of poetic defiance, like Htein Lin’s video The Fly (Paris) (2008), based on a performance he’d enact while a political prisoner in (again) Myanmar: bound, naked, to a chair until he catches a fly in his mouth, at which point he ‘becomes’ the fly and, energised, frees himself. And, commanding the top floor, there’s the installation Joker’s Headquarters. Gesamtkunstwerk as a Practical Joke (C’est le Premier Vol de L’Aigle) (2025), by Sawangwongse Yawnghwe (again from Myanmar; interviewed, Colah said she had strong links to the artistic community there, which is obvious). Here, amid banners tabulating global arms-dealing, the artist appears on video in Joker makeup, melancholically outlining a world built since forever on the big business of war, and unlikely to change.

At the nearby Sophiensæle (usually a performing-arts venue) the relatively high production values of the KW show promptly fall apart in what looks like an incoherent, messy little student show. Here are perhaps overambitious works like Amol K Patil’s mixed-media BURNING SPEECHES (2025): one part of it, a little vintage radio, plays barely audible speeches and occasionally emits puffs of smoke, and seemingly links the venue’s history as a flashpoint of leftist activity and housing for unionised workers in Mumbai. And here, seemingly crowbarred in for thematic continuity, is Daniel Gustav Cramer’s Fox & Coyote (2024–25), a pair of photographs comparing a coyote he saw in Death Valley with, yes, a somewhat similar urban fox he saw from his Berlin apartment window. Similarly rough-edged and discontinuous but rather more powerful is the section in the former courthouse on Lehrter Straße, themed around legality, illegality and how artists might intercede amid them. Anna Scalfi Eghenter’s installation Die Komödie! (2025) harkens back to the venue being the site of the 1916 trial of revolutionary socialist Karl Liebknecht, who called his tribunal a ‘comedy’; one room features myriad reprinted pamphlets by Liebknecht blown around by fans; another features annotated global maps referring to what Eghenter sees as the compound background that today’s workers have to (somehow) unite against: global financial markets, agribusiness, tech, big pharma. Paintings produced in prison by the aforementioned Htein Lin – emaciated groups of figures, colourful near-abstractions – would be powerful enough already but are amplified by the historical judicial context. And in Kazakh collective Artcom Platform’s mixed-media installation The Song of Lake Balkhash (2025), the embattled lake – menaced by extraction, climate change, a nearby nuclear power plant – is personified in a video and speaks back, while surrounding friezelike woven objects reflect the Kazakh weaving tradition and the notion of ‘Steppe Democracy’ that has preserved their culture amid colonial oppression. It’s this continual, stubborn, otherwise little-seen determination to remain unbowed and persist that, you realise, unites so much of the work here, across myriad vectors.

By the Hamburger Bahnhof, the fourth venue, you might have clocked that Ukraine is not going to be addressed here either: which might be spun, I guess, as a curatorial determination to swing the spotlight elsewhere, to note that the whole world is on fire or at least embattled. Instead, in Jane Jin Kaisen’s beautifully shot videos on suspended screens, we go to a cave on Jeju Island, off South Korea, to women divers and the precarious sustenance of shamanic rituals. We go to India, where Zamthingla Ruivah Shimray’s patterned sarongs elegise her friend Luingamla Muiano, who was murdered, after attempted rape, by Indian army officers; the sarong has become a folk totem of memory, with more than 15,000 of them having been woven by thousands of women in hundreds of Indian villages since the artist designed the original in 1990. And we go to Argentina, and the brightly coloured, diversely iconographic retablos or folk-altars-on-sticks of Gabriel Alarcón, used in a march against international mining rights being granted in the so-called Lithium Triangle across Argentina, Chile and Bolivia.

All of this matters, a lot, individually and collectively. But the show’s omissions are evidence that artists not only need to try and fox oppressive political systems but, sometimes, their own gatekeepers too. And when they can’t or won’t, it’s further evidence – against the sometimes-romantic hopes for which this biennale tends a flame – of the real limits of art.

13th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art: passing the fugitive on, Various venues, Berlin, through 14 September

From the September 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.