The biennial-as-séance only works when the spiritual world collides with the ‘real’ world

What’s a biennial these days if it doesn’t take something you think you do know and prove that, in fact, you don’t? In the last Venice Biennale that ‘something’ was foreigners or the idea of foreignness; here it’s spiritualism, which the contemporary cynic might associate with hippies, counterculturalists in general, the religiously devout or those who wish to immerse themselves in any reality other than the one we’re stuck in now. In this exhibition, however, which features work (most of it housed within the Seoul Museum of Art – SeMA) by 50 international artists and collectives, spiritualism is reconstituted as a science rather than a delusion, and as the very foundation of modern art. Because if art is a spiritual practice, then like spiritual practices in general it’s a means of attempting to know or at least understand the world, which, as far as this biennial is concerned, is what art’s supposed to be about. You might even call that optimism.

Yet the symbol for this is drawn from the world of the fantastic: Wamidal, a cat-faced, goat-legged demon depicted in a giant reproduction (from a German eighteenth-century grimoire) suspended from the ceiling of SeMA’s lobby, births dragons out of her gaping vulva (she’s holding it open to ease the process) while flames lick out of her ears. She leers at visitors grotesquely, her sagging teats dangling over her potbelly, as they proceed into a darkened space that announces the show proper. SeMA is housed in a modern building tastefully slid behind the facade of Seoul’s former Supreme Court. In this context, Wamidal appears rather like a leather-clad dark-metal fan flaunting their tattoos while sipping tea in a fancy hotel: all surface; fancy dress. But it does remind visitors that the artistic armature of this exhibition, curated by Anton Vidokle, Hallie Ayres and Lukas Brasiskis, collectively of e-flux, is, despite its internationalism, firmly grounded in the arc of Euro-American art history. Strangely, given the subject matter, South Asia is a notable blind spot. The subcontinent, from which so many spiritual practices were birthed, is represented by Amit Dutta alone, whose films are on show at Nakwon Sangga, a shopping centre for musical instruments that also houses the biennial’s fascinating satellite exhibition of audioworks in a darkened listening lounge.

Once inside the exhibition space at SeMA we’re confronted with more reproductions, this time of philosopher, social-reformer and self-proclaimed clairvoyant Rudolf Steiner’s blackboards (produced during lectures about anthroposophy – a belief in a perceptible spiritual world accessible by thought), which document the Austrian occultist’s quest to find a spiritual science. ‘Imagination’, ‘Inspiration’, ‘Intuition’ intone the words on one of these dramatically spotlit, vaguely diagrammatic scrawlings, which look like a cross between colour charts and Venn diagrams, this one dated 19 February 1922. A wall text, emphasising the works’ status as a détournement of the received wisdoms of Western art-history, suggests that they in fact represent ‘an action painting of the mind’. Nevertheless it’s not entirely clear what audiences are supposed to make of Steiner’s ‘works’, beyond inhaling the faint but entirely imaginary whiff of pedagogy and chalk dust.

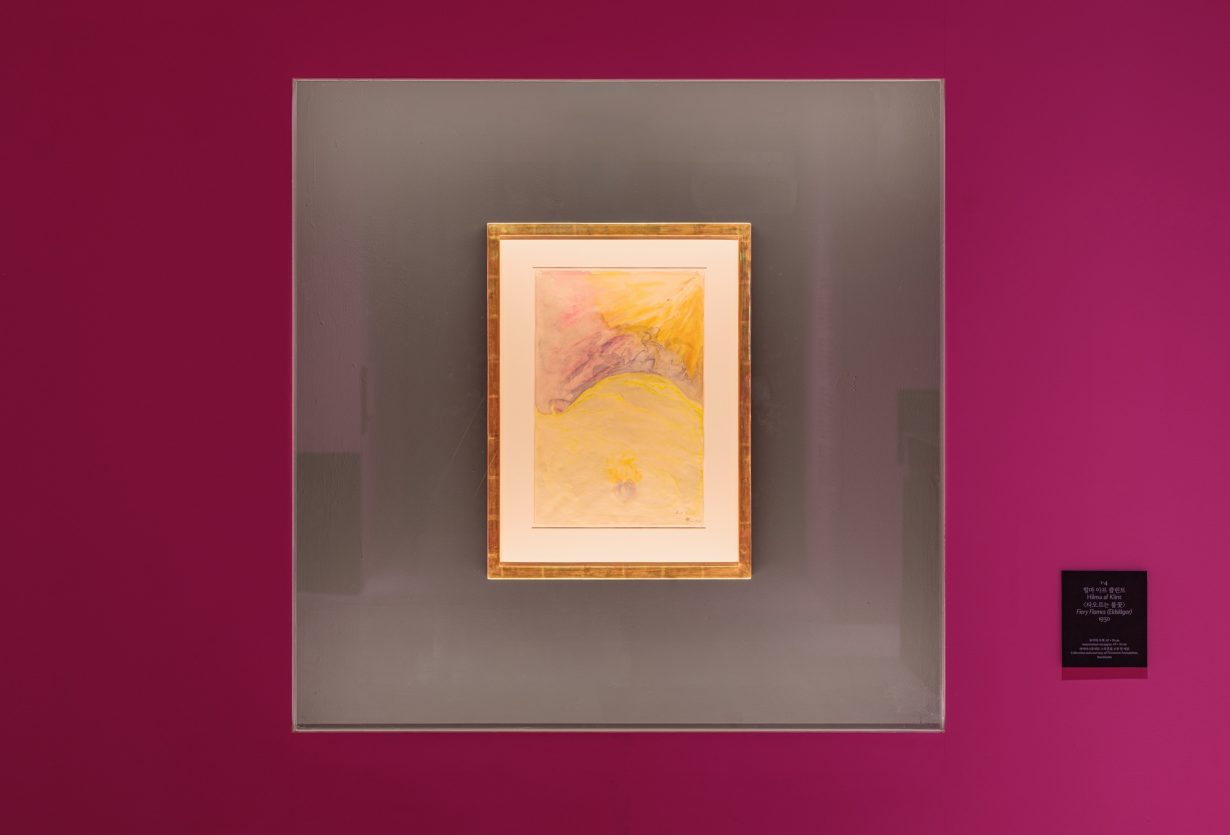

And so we breeze on through, out of the darkness and into the bright light of a pink-walled room, which triggers disturbing echoes of the anatomy Wamidal was recently showing off and, less disturbingly, further builds an art-historical foundation for what is to come with works by nineteenth-century British artist and spiritualist Georgiana Houghton (spirit drawings that she allegedly made via the guidance of angels), turn-of-the-twentieth-century Swedish mystic and artist Hilma af Klint (guided by a spirit to create a temple), early-twentieth-century Swiss healer and artist Emma Kunz (geometric mapping supposedly indexing healing energies) and a collection of more obviously Christian prints from the 1960s by American Sister Corita Kent. Collectively these works introduce one of the biennial’s central theses: that art is a means by which to search for patterns in an otherwise disordered and nonsensical world. To emphasise that, the biennial is divided into a technicolour display of brightly coloured ‘zones’ (covering the walls and floors) that leave you feeling like you walked, Dorothy-style, into a colour-TV test card.

At this stage there are other emerging thematics too: that abstraction in art developed not as an aesthetic revolution but as a spiritual revolution; and relatedly, that abstract art was not a rejection of the world, but an attempt to understand it. Which, a cynic might say, is an attempt both to recognise and to formulate a response to the more general paranoia that surrounds artistic practice today: is it actually useful, important or even relevant to the world in which it resides?

So, a display case of decorative ceramic cups by twentieth-century religious leader (cofounder of the neo-Shintoist Oomoto religion) Onisaburō Deguchi, each of which was apparently made, following his release from imperial prison in 1944, while reciting a prayer channelling god’s will, is presented as a ceramic chunk of the divine, evidently wearing the disguise of a practical drinking vessel. It’s hard to look at the cups, with Onisaburō’s most famous catchphrase – ‘art is the mother of religion’ – rumbling through your head, without some degree of bemusement, however beautiful they may be. As with many of the previous works, the medium is not the message. That’s in the supporting materials of captions and wall texts rather than in the objects in front of you.

Unless, that is, you’re looking at Suzanne Treister’s HEXEN 5.0 (2023–25), a tarot deck of 78 watercolours in which, for example, The Fool (normally symbolising a leap of faith) is represented by the blockchain with its associated technologies, benefits and drawbacks, all neatly housed in a wheel of fortune. It’s these types of works, in which the spiritual world collides with the ‘real’ world, that make the themes of the biennial seem more urgent and more alive.

This comes to a head most vividly and urgently in Hiwa K’s You Won’t Feel a Thing (2025; one of the biennial’s newly commissioned works), a 22-minute human-scale (as opposed to cosmic-) video narrative recording the Kurdish-Iraqi artist’s treatment for kidney stones. The video follows his diagnosis in a Western-style medical facility and, faced with surgery, the second opinion he sought and the noninvasive cure he received from a traditional healer (who uses his ‘laser’ eyes as a surgical tool to break up the stones), who charges a lot less than his ‘modern’ counterparts, is, according to this narrative, extremely effective and is consequently being harassed by the forces summoned by that ‘modern’ medicine and the capitalist system in which it is enveloped. Crucially, the video opens with shots of the artist attending to his farm, connecting to the land; a reminder that even for spiritual practices, some grounding in context is important. It’s a message that works such as the Karrabing Film Collective’s video The Family and The Zombie (2021; which examines the impact of settler colonialism) also emphasise, perhaps as a cautionary note to contextless gatherings or zones of equivalence that form the general bedrock of largescale exhibitions such as this one.

A dialectic similar to that proposed by Hiwa K is at play in Thai filmmaker Anocha Suwichakornpong’s Narrative (2025), a 49-minute video that indirectly centres on the April–May 2010 killings, by government forces, of pro-democracy protesters in Bangkok. The work contrasts Buddhist rituals of commemoration with what appear to be role-playing therapy sessions for relatives of the victims of the massacre (but are actually, we are told in an accompanying text, rehearsals for another movie about a fictional trial of the perpetrators of the killing), who, 15 years later, remain trapped in a labyrinth of legal bureaucracy that appears to be expressly designed to prevent them from obtaining justice for their loved ones. Just as much as the participants in the video are performing justice, so too the justice system in which they are mired seems little more than a performance on the part of the Thai authorities. And naturally, the Buddhist rituals are a type of performance too, just as ‘rehearsal’ might, in this context, be figured as a training for and understanding of life. What you so clearly walk away with, at the end of this work, is the idea that whatever the world is, it’s made up of multiple histories or narratives, only one of which is our own. Which might, despite the exhibition’s attempts to tie everything together, be a summary of this biennial as a whole.

The 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: Séance: Technology of the Spirit, Seoul Museum of Art and other venues, through 23 November

From the Winter 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.

Read next ArtReview met with the the curators of the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale to discuss the biennale’s history, AI and the potential of mediation