When I saw Helen Marten’s work for the first time, I was immediately interested in the particular freedom she takes in her use of codes and languages. I see in her work a change from what we know of artists and the way that they employ references, something that has become very popular since the Internet became the primary tool for research. We’ve already seen artists who reference the histories of art, design and architecture, but now, with Marten’s work, it’s more like we’re seeing the Internet as a life tool – something that has equal reality to that of the physical realm. I was very impressed by the sureness in her use of materials and particular iconic images and signs.

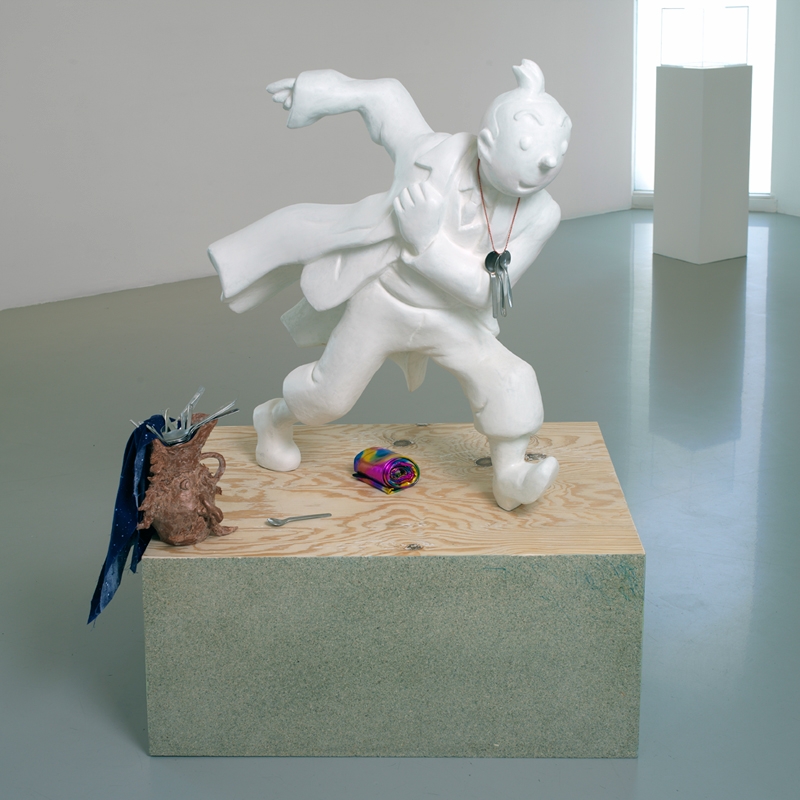

In All the Single Ladies (2010), Marten has taken defunct mobile phone handsets and set them in pale pink cast Corian (a product commonly used for everything from kitchen surfaces to architectural cladding), with eyebrows and lips that look as though they were taken from Betty Boop’s face engraved into the surface. George Nelson (2009) is a screenlike structure made from Plexiglas in the kinds of colours employed by the famous American designer after which the work is named, though it also seems as though it might have been constructed using some kind of kit. In works such as these, Marten applies handicraft to prefabricated material, mixing up art, design and production history with items that you fi nd in digital information or comics. What this amounts to is a very visual form of storytelling. It’s almost archaeology, and at the same time, it’s always from the present. Her work considers not only global codes and languages, but who owns these things. Who owns tartan? And who owns a particular beige tartan? This is a wonderfully humorous way of critiquing the reference system in art with which we have become so familiar, and also of highlighting how the ways in which the visual has become coded have changed everything.

This article was first published in the March 2011 issue.