Sixty years ago, at the first Bienal de São Paulo – then organised along national lines like Venice, the only recurring international exhibition that’s been around longer – Max Bill, the Swiss artist, was awarded the first prize in sculpture. Like the event itself, the selection signalled São Paulo’s wealth and international cultural engagement; but it also came at the start of a decade during which Brazilian artists and critics urgently debated what political role abstraction – like Bill’s – might play in their rapidly developing nation, and perhaps more cogently, how art might result from and influence the coincidence of the individual and the social.

The 30th iteration of the Bienal attempts to interrogate both the form and content of the sprawling survey exhibition in similar ways. It is conceived less as an overview of recent trends than a philosophical exploration of the way art works. At its core are the ideas of poiesis: the Greek root of poetry, which means actualisation or becoming; and imminence, the sense that this actualisation takes place whenever a viewer engages with an artwork. The exhibition is laid out in nine clusters, each the subject of a podcast by Luis Pérez-Oramas, the show’s chief curator, that lead the viewer through an explication of the process.

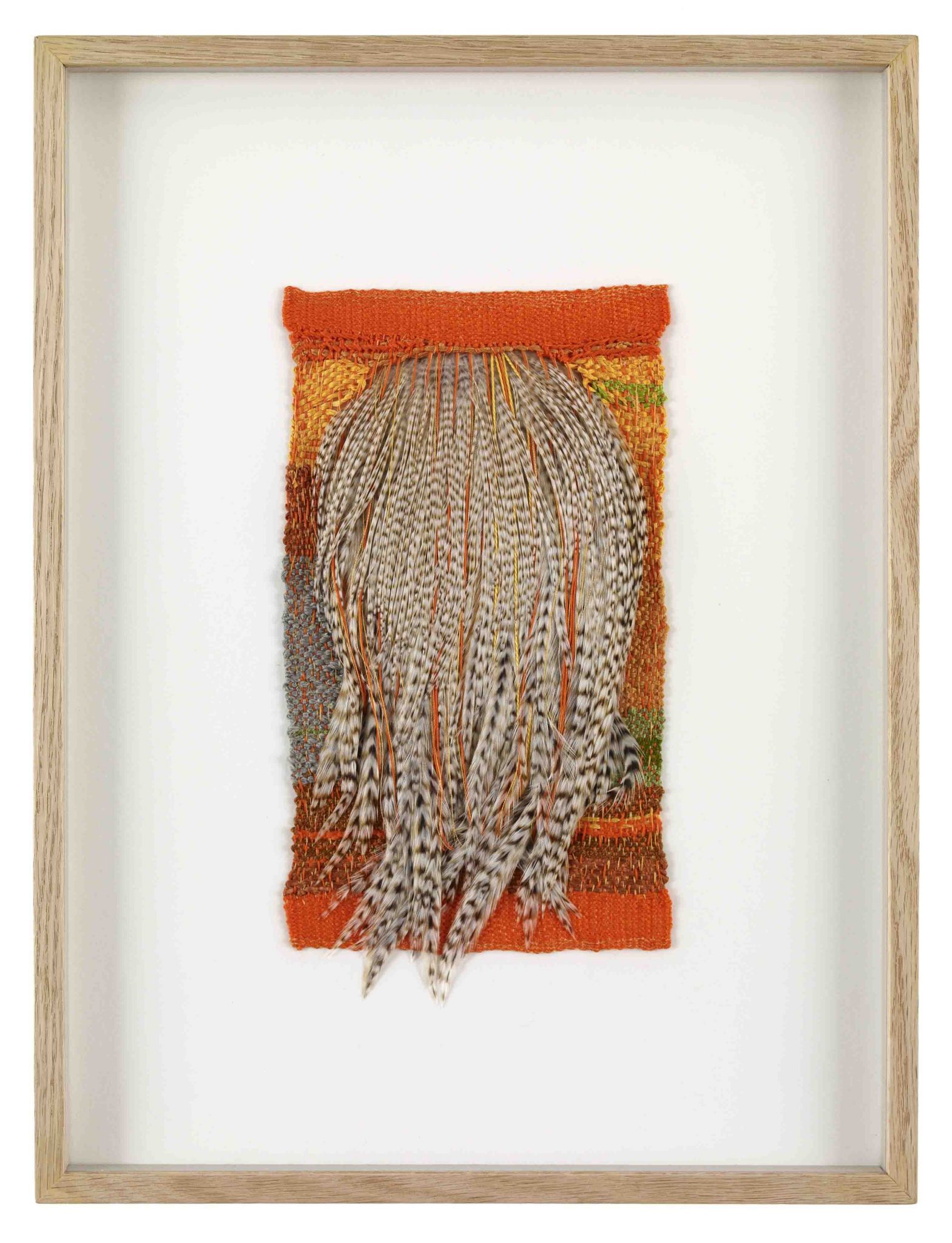

Crudely summarised, the stages start with material, the stuff things are made of, and move through representation, labour, subjectivity, recontextualisation, the categorisation of knowledge, the individual vs. others, architecture and finally, society. The show begins with, among other examples, the weavings of Sheila Hicks, which foreground the colour and texture of substances as diverse as feathers and rope, and ends with August Sander’s epic photographic series, People of the Twentieth Century. Exhibited in its entirety, it forms a portrait of the body politic in Weimar Germany.

Everything in the show, however, can be related to many, if not all, of the nine stages. In revealing the architecture of society, Sander for instance draws on the categorisation of knowledge (the class system) as well as representation (in the form of the photograph) and the concept of the individual. In its way, his series is also a weaving; a connection that loops back to Hicks’s work. Displayed here with the notebooks she kept on research trips to places such as Peru, Mexico and Japan, Hicks’s own pieces are also about labour and how traditions are updated and abstracted in works of art.

Once the viewer starts making such connections, associations ping back and forth across the exhibition. This associative process – all the categories working together – is poiesis, the thing that effects poetry. It turns the exhibitiongoer from a consumer of content laid out by a curator into a participant who creates meaning for him or herself, and I suspect it is meant to make the entire Bienal a mechanism of interactive communication.

Concurrently, Pérez-Oramas sketches a history of socially and viewer-engaged work. Hanging near Sander’s magnum opus is a selection of homoerotic photographs of young men by the Brazilian engineer and artist Alair Gomes (some taken in his studio, some with a telephoto lens out his window), and across from them, Mark Morrisroe’s elegiac photographs of friends shot during the 1980s in New York’s East Village. The pairing suggests that communities are imagined or created, Morrisroe’s around shared sexual identity and experience; Gomes’s around his idealisation of classically handsome young men and their knowing projection of a charged masculinity. Similarly Jiří Kovanda’s actions, like laying sugar around a street corner, documented in black-and-white photographs, were meant to draw attention to the individual and, as acts of personal communication, intended to disrupt the conformist social veneer in Communist Czechoslovakia.

Art like this raises ethical questions about who is speaking to whom and why. The selection of work in the Bienal suggests an answer that demands that art act as an agent of individual and community empowerment. But the question of communication must also be applied to the exhibition itself. This is a self-imposed test, and the show fails it. Most of the work here is either discursive – Alejandro Cesarco’s analyses of how texts function, to give but one example – or depends on the combination of disparate objects in supposedly provocative ways, a practice that has become an overused artistic lingua franca. According to the many – overly obtuse – wall texts, both approaches reveal the ‘poetic’; however, this oft-used word is never defined. Whatever the curators meant by it – I arrived at my own definition by force of will – might be revealed in the catalogue essays. But these are rife with multiple references to twentieth-century European theorists and recent curatorial conversations about, for instance, whether biennials can function as early warning systems for social change. If there is a poetics involved here, it is one of the academic mind, not the artistic experience of the large audience.