ArtReview sent a questionnaire to a selection of the artists exhibiting in various national pavilions of the Venice Biennale, the responses to which will be published over the coming days. Richard Mosse is representing the Republic of Ireland. The pavilion is located at Fondaco Marcello, San Marco 3415 (Calle dei Garzoni), 30124 Venezia

What can you tell us about your plans for Venice?

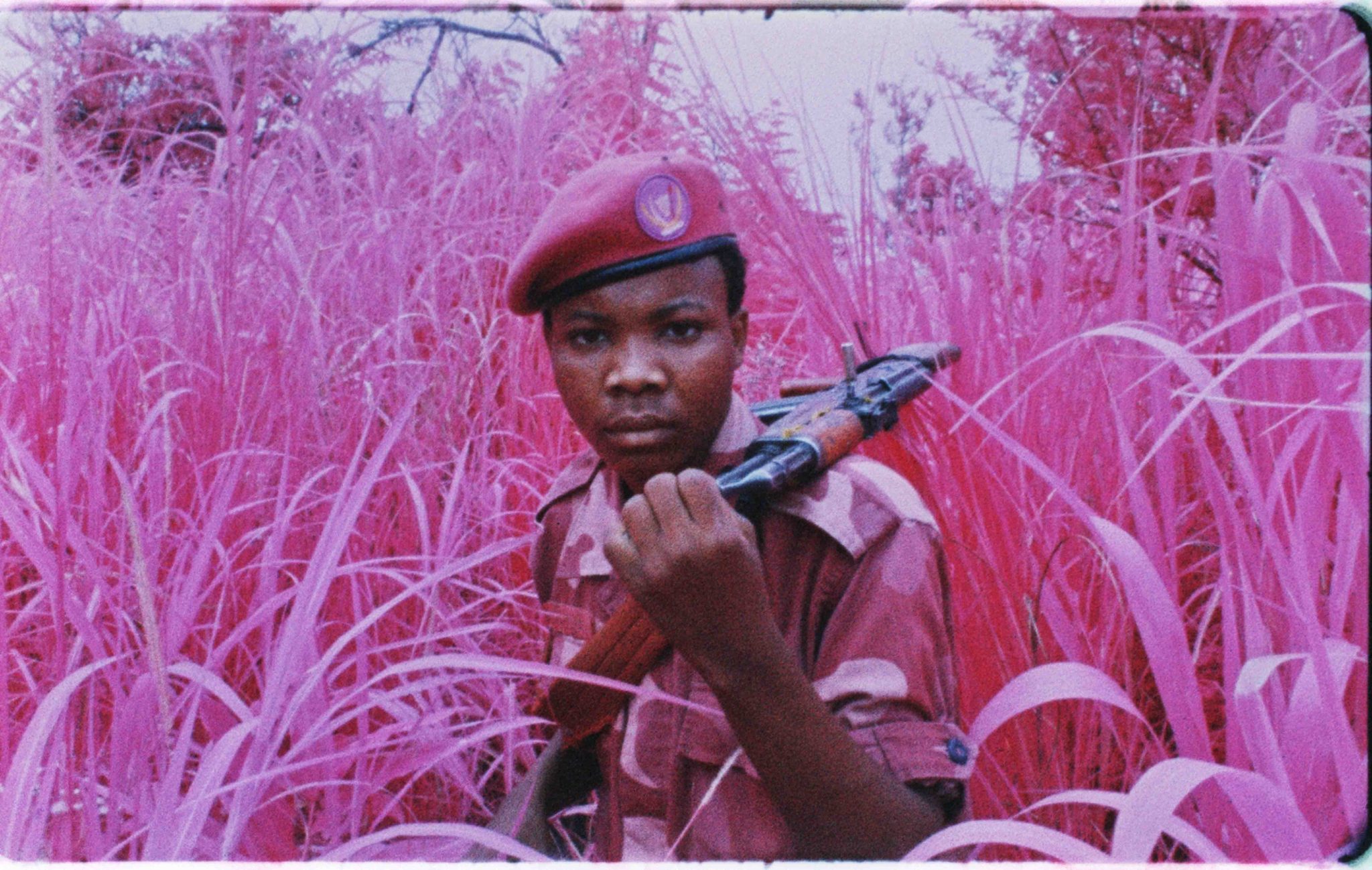

I’m showing a new multi-channel film, The Enclave, which was made in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. The film was shot on an extinct 16mm infrared film, which was originally designed for military reconnaissance, and renders the jungle war zone in disorienting psychedelic hues.

Are you approaching the show in a different way to how you would with a ‘normal’ exhibition?

It’s a new approach for me because this work has been a deeply collaborative effort. In the past I’ve preferred losing myself to anonymous nomadism, where I’m accountable to no one, and my process doesn’t need explaining until much later, when the ideas have fully resolved.

Working closely with the musician Ben Frost, the cinematographer Trevor Tweeten, and the writer John Holten – in some extremely challenging situations – has been a remarkably different process, perhaps even more intuitive in some respects. Congo threw some punches along the way, and we had to learn to roll with those in order to produce this work. I guess that’s always been a part of my practice, but when you have a team, a schedule, and a very definite deadline (Venice), it hardens into an intuitive philosophy: embracing failure, admitting defeat, and through that, allowing the world to reveal itself.

The installation itself embraces the architecture of the Irish pavilion, the Fondaco Marcello. The Enclave unfolds over six screens installed inside a large darkened chamber. The screens are custom built steel frames with rounded corners exactly replicating the camera gate of an Arriflex SR-2 movie camera, which was used to shoot the film. By placing each screen adjacent to a column, my hope is to activate the pavilion’s architecture, working with it rather than resisting the columns, which are difficult to work around. The screens can be viewed from both sides, creating a sort of sculptural labyrinth within the space. The viewer must actively participate in the piece spatially, moving through the chamber according to the work’s emphasis of sound and vision. It’s a very disorienting experience.

What does it mean to ‘represent’ your country? Do you find it an honour or problematic?

It’s a problematic honour. I never felt entirely Irish in the Fenian sense, and have even been called a “plastic paddy” by a barmaid in a mid-town Manhattan Irish pub. (That happened in the presence of a MoMA curator, which was hard to live down.) Beyond my own sense of national identity, and nationalist conviction, I think the idea of a World Cup of contemporary art is a ludicrous concept. Irish football fans have always been desperate for the Irish team to qualify for the World Cup. Sadly we didn’t qualify in 2010, so Irish fans collectively decided on national radio to support the Ivory Coast. Why? Because their flag is the reverse of the Irish tricolour: orange, white, and green instead of green, white, and orange. That kind of happy inverted nationalism seems like a good approach for the Venice Biennale too.

Ireland, like Congo, is a young nation with a troubled recent past. In fact, Ireland’s history has sometimes entwined with Congo’s. Roger Casement, our famous martyr revolutionary, was one of the most outspoken human rights activists. Ireland also sent many peacekeeping troops to Congo since the Sixties, under the United Nations. The biggest loss of life of Irish troops occurred in Congo in 1960, known as the Niemba Ambush. As a teenager, my best friend’s father was shot in the head while working for the UN in Congo.

What audience are you addressing with the work? The masses of artist peers, gallerists, curators and critics concentrated around the opening or the general public who come through over the following months?

I guess I’m just trying to address my own experience, to resolve this extremely intense series of journeys in Congo as best I can, and to bring the work to an adequate conclusion. For much of the last three years, that process has been a very uncertain, ambivalent, and sometimes traumatic trajectory. So it’s really about my own direct relation to the work itself. Is that a valid answer to your question, that the work itself is my target audience?

What are your earliest or best memories of the biennale?

My first experience of the Biennale, and Venice itself, was the most memorable. I travelled with fellow students and our tutors from the Goldsmiths MA in Fine Art, and was blown away by the city’s architecture, drank far too much Illy and prosecco, and wound up having a short fling with a married woman from Turkmenistan. It was a voyage of discovery. The art was great too.

You’ll no doubt be very busy, but what else are you looking forward to seeing?

Very excited to see Marwa Arsanios, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Phyllis Galembo, Ragnar Kjartansson, and Michael Schmidt in Massimiliano Gioni’s curation. From the pavilions, I’m particularly looking forward to Alfredo Jaar for Chile, Jeremy Deller for the UK, Sarah Tze for the States, Simryn Gill for Australia, Jesper Just for Denmark, Akram Zaatari for Lebanon, Luigi Ghirri for Italy, and Constantinos Taliotis for Cyprus.