From sculptural sound and surveillance photography to British horror and ‘digesting’ paintings – our editors on what they’re looking forward to this month

Tatsuyuki Tanaka: Day of the Clockwork Bodhi Brain of the 5th Dimension

Gallery Nucleus, Alhambra, California, through 16 October 2022

Take a deep dive into the cyborg fairytales of Tatsuyuki Tanaka, as the legendary illustrator showcases a series of new works in this brief but intriguing solo exhibition. Known to many for his work on Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira (1988) – a key animator in the scene in which a mutation bursts through Tetsuo’s bionic arm – here the artist offers up a sequence of sketch-and-illustration pairings, in which a dizzying array of cyberpunk heroes, demons and deities set a ramshackle future cityscape in motion. En Liang Khong

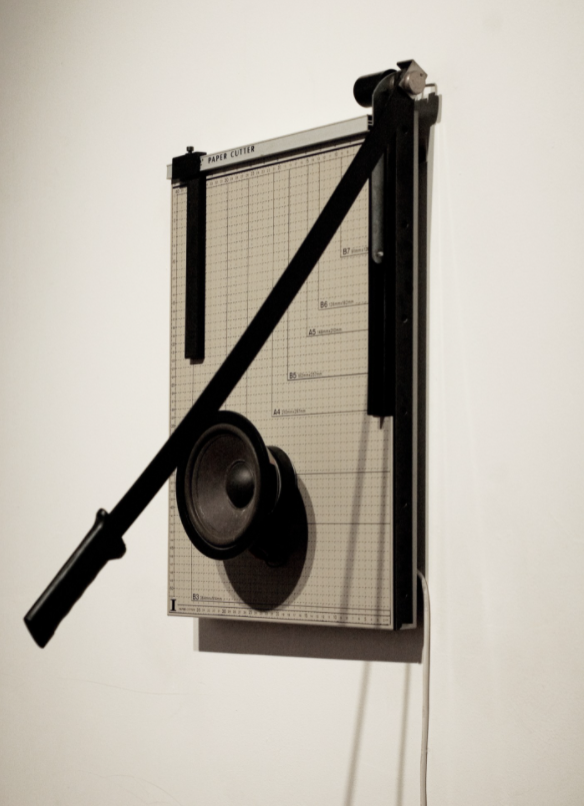

Richard Garet and Diego Masi: Transhemiférico

Museo Gurvich, Montevideo, through 11 November

Separately Diego Masi and Richard Garet have long been investigating the sculptural qualities of sound, their works ranging from a kinetic sculpture in which microphones are slowly lowered in and out of glasses of water (Masi’s Temporada, 2020) to a wall mounted paper guillotine, attached to which a speaker broadcasts the sound of a paper being cut (Garet’s CUT, 2014). It makes sense, then, that the Uruguayan pair are brought together for a homecoming two-person survey. Transhemiférico, which also involves various collaborations between the two, opened with a performance. At one point Garet used a violin bow to play the rails that fence off the stairs into the galleries; at another Masi played a lap harp with a couple of small stones. This noise was then layered and interwoven in a strange aural abstraction, typical of artists whose individual careers have been dedicated to a transformative – and often humorous – play between mediums. Oliver Basciano

Josephine Pryde: The Vibrating Slab

Art Institute of Chicago, through 30 January 2023

Life in capitalist society takes on a particular look, born of its attachment to the mystique of consumer objects, the sheen of glamour and leisure lifestyles, and, unwittingly, a sense of paranoia about what it means to be an individual in the midst of all this. British artist Josephine Pryde’s photographs manage to refract these tensions and anxieties, in images which possess their own weird allure; from photographs of sports cars being splashed in paint, to glittering portraits of guinea pigs, to the more recent series of women’s manicured hands caressing smartphones and tablets. Pryde has invented a look that embraces the glamour of images of glamorous things (and people), but also knows that this culture is almost worn out. J.J. Charlesworth

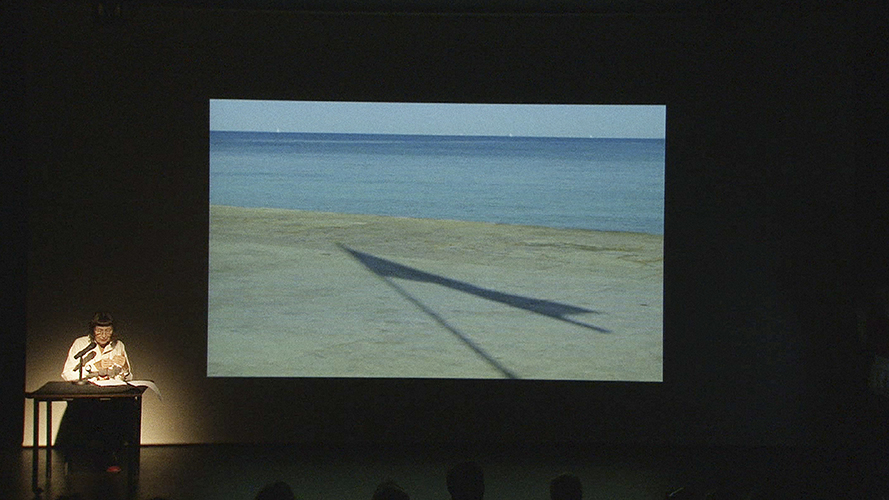

Sanja Iveković: Works of Heart (1974–2022)

Kunsthalle Wien, 4 October – 12 March 2023

Sanja Iveković, a preeminent artist of the former Yugoslavia, is the subject of this career review at Kunsthalle Wien. Finding the space between feminism and surveillance to be fertile ground, Iveković is viewed here through her work’s commitment to antifascism and socialism: take a filmed lecture, Why an Artist Cannot Represent a Nation-State (2012), which uses institutional critique to make an equally personal statement of identity. Elsewhere, photographs from contrasting eras, The Right One. Pearls of Revolution (2007-10) and Make Up (1979), propose femininity as a subject of surveillance and commercial construction; Women’s House (Sunglasses) (2002-) transposes fashion advertisement as an imagery for highlighting violence against women by cutting stories of their suffering – itemised by name, age, nationality, marriage and parental status – over fashion-house photographs, aping the methods that mythologise the idea of a woman. Other works previously featured at Documenta 13 and Gwangju Biennale are not to be missed. Alexander Leissle

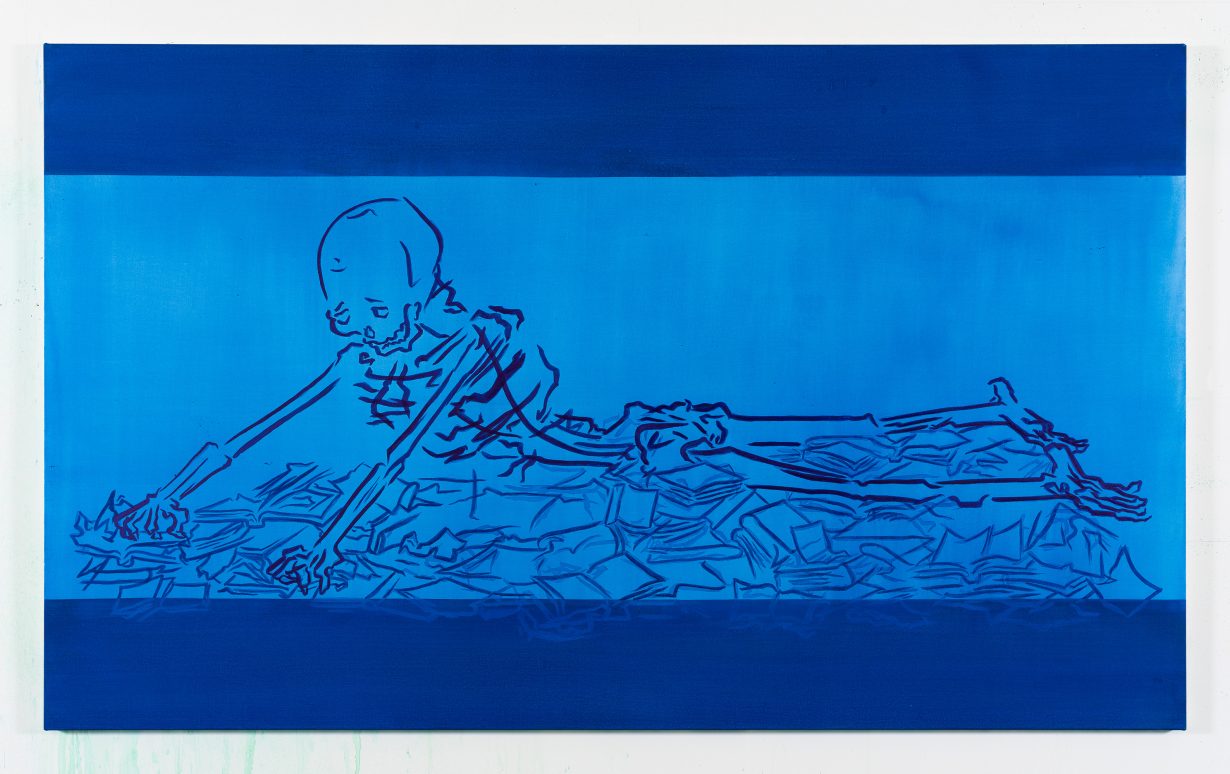

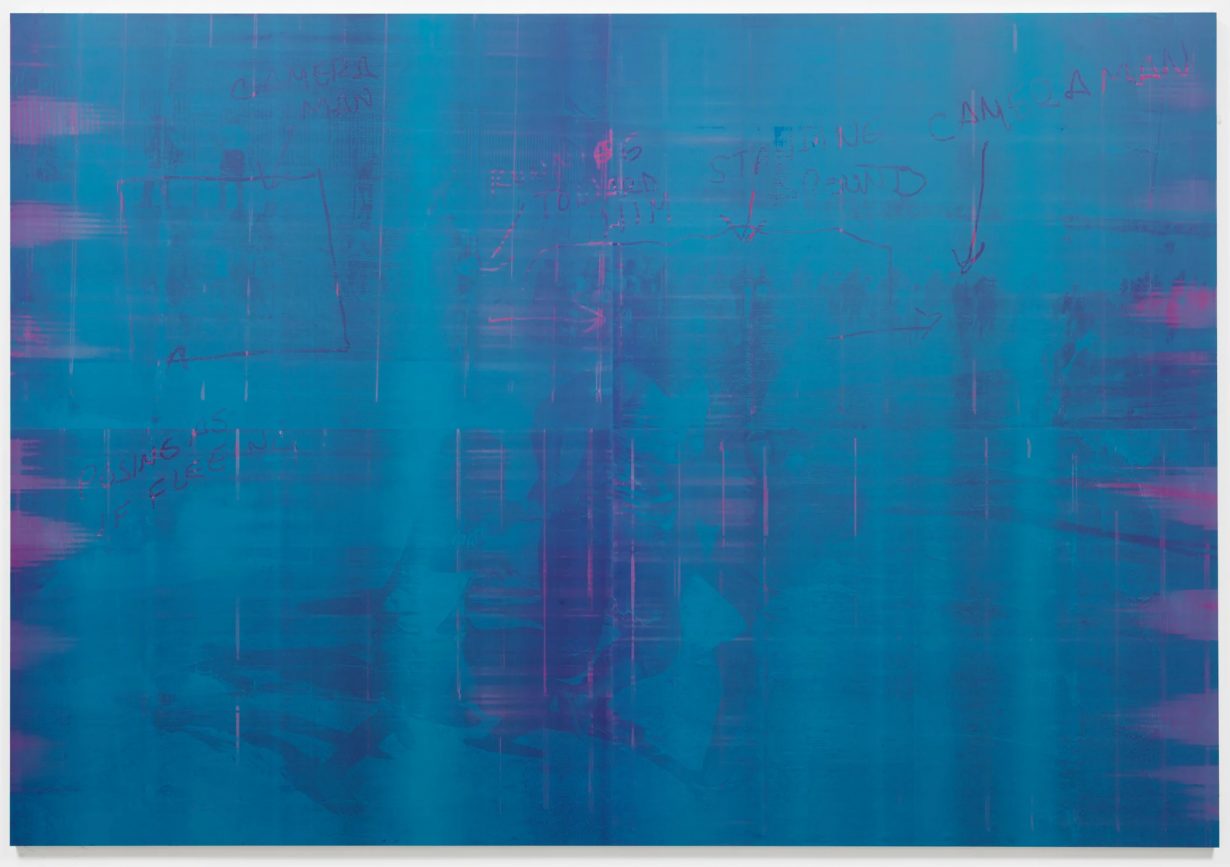

Brook Hsu: Oranges, Clementines and Tangerines

Kiang Malingue, Hong Kong, 6 October – 12 November

In Brook Hsu’s first monograph, Norwegian Wood (2021), a green gloom settles over the pages. Emerald, forest and radioactive hues dominate her paintings, interspersed, occasionally, with dull blues and sprays of red. In her figurative work, a green self-portrait looms out of its green background, an emerald-coloured skeleton with demonic horns peers down a hexagonal well, while other skeletons embrace in a forest. Then there are horses, rabbits, frogs, and the artist’s beloved and deceased dog Aesop, painted repeatedly, obsessively. In more abstract paintings, violent streaks of black paint swirl and cross, obscuring the faint blue eye of a portrait lost in the vortex. There are paintings on carpets too: scruffier, with a hasty messiness to them. Like in We can go and leave the cats to read Shakespeare (2019), where four frogs scrawled in black ink dance in ecstasy under splotches of luminous green. But if you’re in danger of slipping into the verdant dreamscape of Hsu’s output, there are works in her latest exhibition at Kiang Malingue’s newest gallery space in Wanchai that will threaten to wake you up with a bright blue slap: Olympia (2021) depicts a panic-stricken skeleton lying atop a bed of books, clutching crumpled volumes between its bony fingers. Fi Churchman

Kamala Ibrahim Ishag

Serpentine South Gallery, London, 7 October 2022 – 29 January 2023

This retrospective of one of Sudan’s most prominent painters offers a glimpse into six decades of artmaking. One of the first women to graduate from art school in Khartoum in the 1960s, Ishag went on to found the modernist Khartoum School – alongside the likes of Ibrahim El-Salahi – and later the conceptual Crystalist art group, which reflected her view of the universe as infinite and multifaceted, as seen through a crystal cube. Drawing on influences ranging from William Blake’s exploration of spirituality and incarnation to the spirit-possession practices performed by Sudanese women (known as Zar), Ishag’s cosmic paintings – on canvas, calabashes and leather drums – depict a world where the human and vegetal merge. If some paintings refer to ancestral myths and folklore, more recent works crystallise real-life events: the many moon-shaped faces seemingly floating in a kelp forest in Blues for the Martyrs (2022) immortalise the hundreds of people killed at a peaceful sit-in on what became known as the Khartoum Massacre of 2019, many of whom were drowned in the river. Louise Darblay

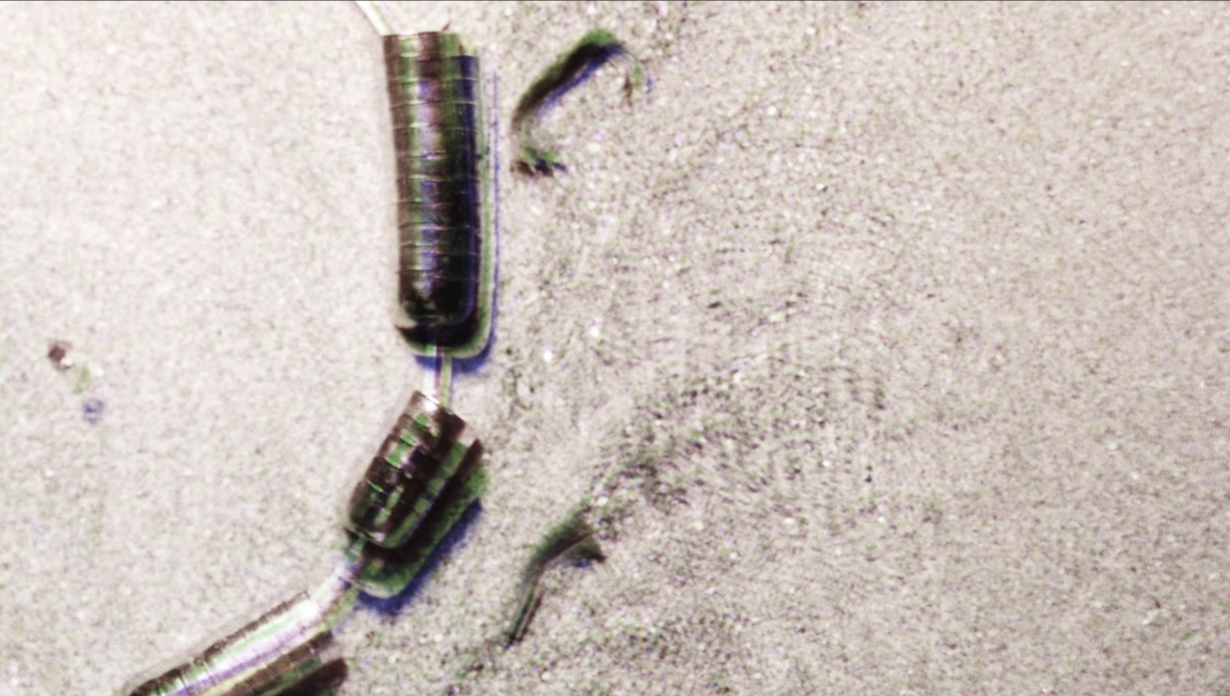

Emmanuel Van der Auwera: Fire and Forget

Edel Assanti, London, 13 October – 17 December 2022

What is left of the human gaze? Fire and Forget, marking Emmanuel Van der Auwera’s first solo exhibition in the UK, mines found imagery sourced from the depths of military archives, internet conspiracy theories and social media livestreaming to offer troubling insights of an age in which fast-developing surveillance and artificial intelligence technologies are redrawing and indeed reconstructing the parameters of our perception. Such post-truth reflections meld photography, printmaking and paint: the artist offers a sequence of aluminium print plates (showing a panorama of Las Vegas captured by thermal imaging; and a photograph of a mother and her children during the 2018 US border crisis) lifted from a newspaper production line – negatives which, upon exposure to a light source, appear to attain new meaning. A series of LCD screens, which the artist has taken apart with a knife, fill the gallery with harsh white light (the viewer can only access their images by means of filters positioned around the space). En Liang Khong

Decision to Leave, 14 October

Director Park Chan-wook returns with his eleventh feature film, and does so after a brief foray into photography with Your Faces at Busan’s Kukje Gallery. Decision to Leave, however, is unmistakably cinematic: detective Hae-joon becomes infatuated with the prime suspect for a murder, the victim’s wife, as the two try to outmanoeuvre and manipulate each other. If it sounds like a Hitchcockian affair, that’s because it is. The anxiety and asphyxiating spirit of Vertigo (1958) looms over Decision to Leave, a natural extension of 2016’s The Handmaiden which helped consolidate Park’s pivot away from revenge thriller to a more seductively nervous affair. Absurdity, meanwhile, will always be essential to his cinematic language; as in the Vengeance trilogy, busy camerawork signals an ever-present self-reflexivity – is this cinema or theatre, characterisation or puppetry? Alexander Leissle

Cyprien Gaillard: HUMPTY/DUMPTY

Palais de Tokyo & Lafayette Anticipations, 19 October 2022 – 8 January 2023

In 2011, Cyprien Gaillard installed a monumental pyramidal structure of piled-up packs of imported beer, culminating under the skylight of Berlin’s KW Institute for Contemporary Art; during the course of two months, the work slowly degraded as visitors sat on its steps and drank the beer – until it wasn’t more than a kind of chaotic wasteland. The productive potential of destruction has long preoccupied the French artist, who nurses a particular obsession for tracing entropy – the amount of uncertainty, disorder and randomness inherent to any system – within our contemporary world. At the centre of this sprawling, two-venue exhibition is the city of Paris, which is in the middle of ‘frantically restoring its most prestigious monuments and erasing the marks of erosion in preparation for the Olympic Games’: fertile ground for the artist, then, to continue mining the tension between collapse and reconstruction, and see what emerges through the cracks. Louise Darblay

Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere

MIT List Visual Arts Center, 21 October 2022 – 26 February 2023

From effigies made with fungi to an infestation of spiders, reliefs glazed with breast milk and a durational performance involving water cress, Symbionts presents artworks made by fourteen artists who engage with living organisms to consider how human and non-human lifeforms might live interdependently. ‘With-living’, is what the folks at MIT’s art centre call it – encompassing the broad idea that we must ‘reexamine our human relationships to the planet’s biosphere’, presumably in relation to the whole entanglement-thing (it’s all connected, see) and distilling it here in ‘collaborative’ artworks. These include Candice Lin’s current iteration of Memory (2016–) in which the artist collects urine from gallery staff, who then participate in the work by feeding the liquid to Lion’s Mane fungus (used in traditional Chinese medicine to improve human brain function and memory), and Nour Mobarak’s employment of fungi to ‘digest’ a painting made from paper, hair and semen. Not to mention Pierre Huyghe’s contribution to the exhibition, which is to let loose a bunch of arachnids into the gallery space – or, as co-curator Caroline A. Jones puts it, a ‘modest welcoming of spiders doing spider things’. Fi Churchman

The Horror Show!: A Twisted Tale of Modern Britain

Somerset House, London, 27 October – 19 February 2023

If life in 2022 seems bleak and crisis-ridden, then an antidote to all the dismay and despair might be found by travelling back to previous eras of artistic and cultural rebellion. Curated by artist duo Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard and Claire Catterall, The Horror Show! offers an epic ride through five decades of British art, music and counter-culture, looking at how generations of British artists have drawn inspiration from a sense of the monstrous, the spectral and the occult as alternatives and oppositions to orthodox politics and society. With a huge list of participating artists, musicians and cultural icons – including Jamie Reid and Marc Almond, artists such as Monster Chetwynd, Laura Grace Ford, Jake & Dinos Chapman, Zadie Xa and Jesse Darling, filmmakers including Ben Wheatley and Nic Roeg – The Horrow Show! reminds us that artists in Britain have always asserted themselves, even in the worst of times. J.J. Charlesworth