Jonathan Jones at Palais de Tokyo and A Year in Art: Australia 1992 at Tate Modern explore the relationship between Indigenous Australians and the land

These simultaneous exhibitions in Paris and London, exploring the relationship between Indigenous Australians and the land, highlight the political, historical, cultural and spiritual importance of the concept of ‘country’.

At the Palais de Tokyo, Jonathan Jones shines a light on the 1800–03 expedition to Australia by French explorer Nicolas Baudin, which added substantially to Empress Joséphine’s collection of exotic flora and fauna. At the heart of Jones’s display are more than 300 delicate, black-on-cream, 20 x 30 cm embroideries, depicting plant species Baudin and his associates collected. Made in collaboration with members of migrant and refugee collectives in Sydney, where the Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi artist lives and works, the embroideries are laid out in two double-sided vitrines.

On a long wall behind the vitrines, a series of exquisite wreaths made, respectively, from seashells, gum nuts, paper daisies, possum fur, emu eggs and black swan feathers – materials of special significance in many Aboriginal communities – encircle six engravings of Aboriginal people developed from sketches made by artists accompanying Baudin. Jones embraces what for Napoleon was a symbol of imperial power to celebrate both the individuals pictured and the humane and dignified manner (unusual for the time) in which they are portrayed. A lyrical film meshing closeups of the embroiderers at work with images of Sydney’s watery surrounds, and a soundscape inspired by the French expedition’s musical notation of a dance ceremony called a corroboree complete the display.

Jones’s installation is rooted in the personal. Driven by curiosity about his own heritage (the name on his birth certificate of the father he never knew corresponds to that of a member of Baudin’s crew), he has found in an episode of French colonial history a wider story of Indigenous Australian values. ‘Plants, like animals, are for Aboriginal people highly political: they are our kin, our ancestors,’ runs a quote from the artist on the wall.

Today, Baudin’s plant samples reside at the National Herbarium in Paris. For Jones, the Palais de Tokyo show is a collaborative effort to, symbolically, ‘bring them home’. As French explorers presumably did not consult the Indigenous inhabitants before whisking off the specimens, the installation, which will later go on show in Sydney, is for the artist an act of healing that reunites Aboriginal people with their plants, some of which are now extinct in Australia. As part of the process, members of the collectives who worked on the embroideries learned about flora and fauna from the continent’s original inhabitants.

Tate Modern’s group show also explores Indigenous Australian attachments to ideas of land and country. Built around the landmark Mabo judgment of 1992, which overturned the concept of ‘terra nullius’ (the idea that nobody owned the land white settlers had occupied), the show features Indigenous Australian art from the past 30 years. It opens with a wall text introducing Eddie Koiki Mabo, a longstanding campaigner for Indigenous land rights (who died from cancer five months before the judgment was delivered), then presents a handful of works that fits the stereotype many gallerygoers outside Australia still have of Aboriginal art, from ‘dot paintings’ by Emily Kame Kngwarreye to bark work by John Mawurndjul.

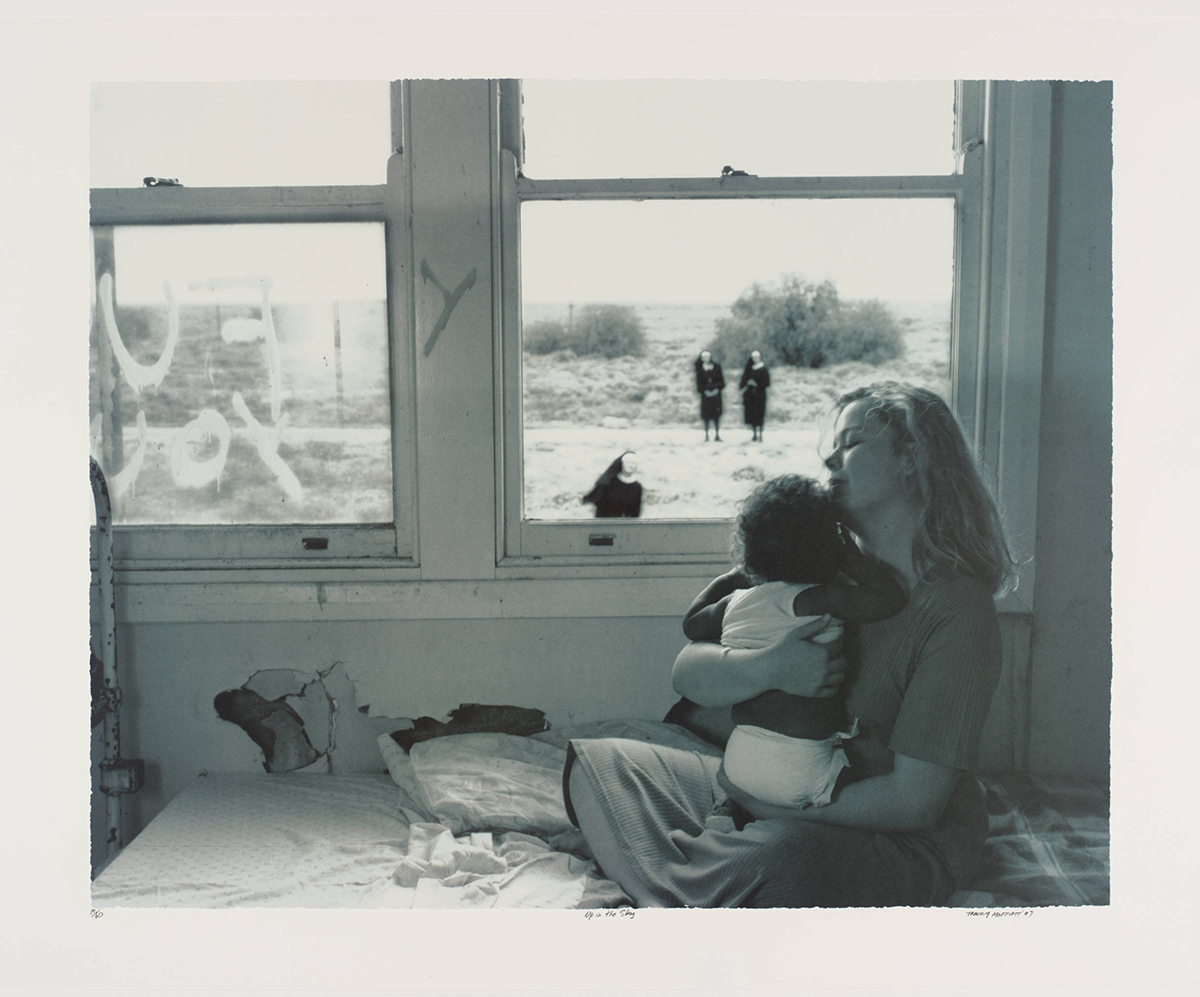

However, the 30-plus works by eight artists that follow may come as a surprise. Gordon Bennett meshes European art-historical references with ironic comment on colonial history – in Possession Island (Abstraction) (1991) he reworks a nineteenth-century etching of Captain Cook’s arrival by obscuring a Black man holding a tray of drinks beneath Kazimir Malevich-inspired squares in the colours of the Aboriginal flag; Judy Watson’s bloodstained works from 2005 draw on documents from the Queensland state archives to underline the brutality of official attitudes; and Tracey Moffatt’s eerie 1997 photographic series alludes to the ‘Stolen Children’ era of government-mandated removal of children from Aboriginal families from the early 1900s to the 1960s.

The pathbreaking, First Nations-led 2020 Biennale of Sydney, curated by Brook Andrew – like Jones, a Wiradjuri artist – underlined the rise of a generation of mainly urban Aboriginal artists intent on interrogating their heritage. Over 20 or more years, these artists have persuaded parents and grandparents to open up about painful episodes in their history; today they collaborate with their elders to bring Indigenous knowledge and stories to light through the diversity of their art. Australia 1992 and untitled (transcriptions of country) reflect that process and invite white European audiences to reexamine their perceptions of the world.

Jonathan Jones: untitled (transcriptions of country) is at Palais de Tokyo, Paris, until 20 February; A Year in Art: Australia 1992 is Tate Modern, London, until Autumn 2022