Ecclesia (The Meeting of Inheritance and Horizons) (2024) is at once spiritual and secular, a mélange of carefully constructed illusions

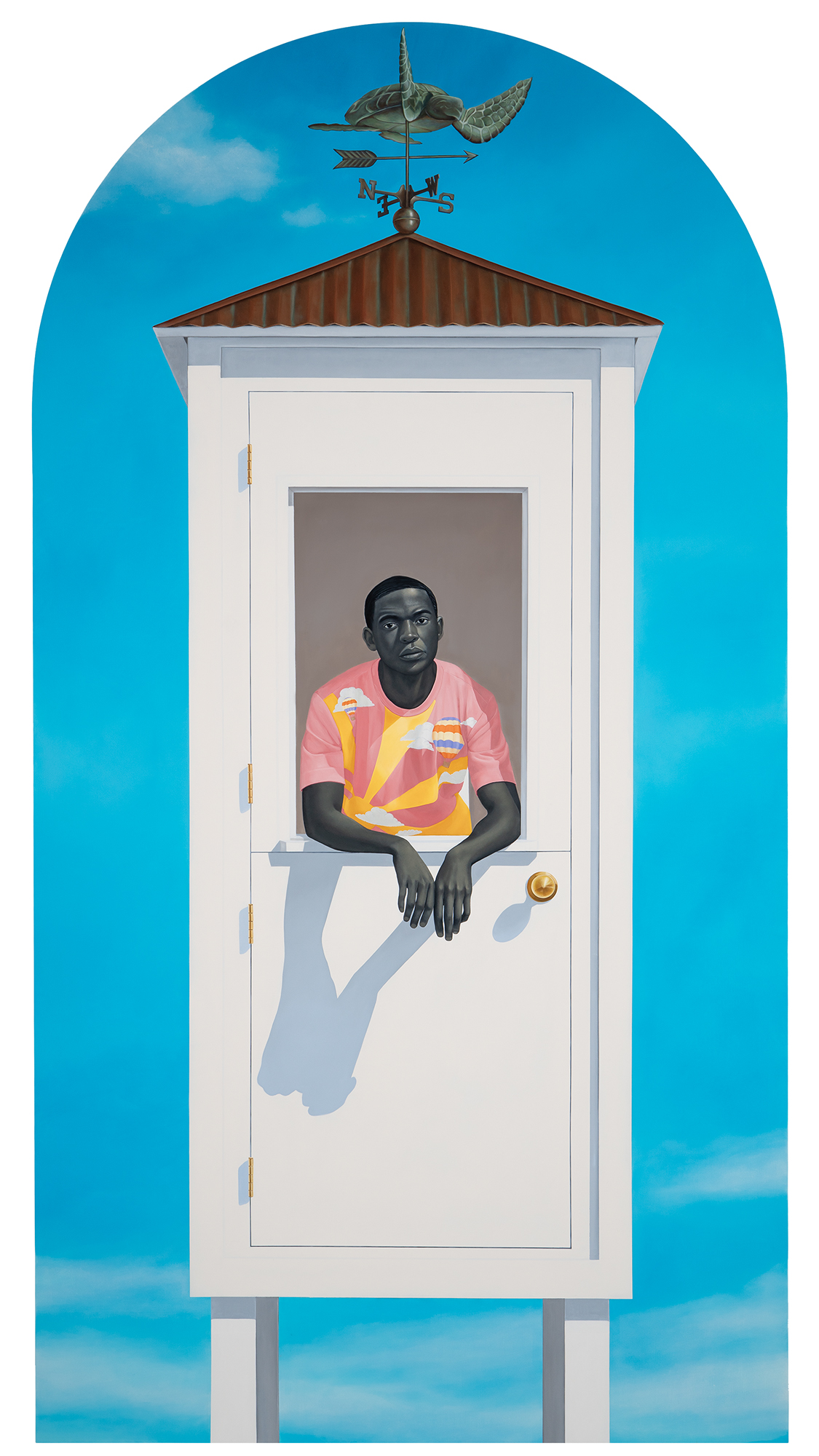

Apart from the Jersey City-based artist’s career-defining 2018 portrait of former first lady Michelle Obama, most of the four dozen single-panel paintings in Amy Sherald’s midcareer survey American Sublime capture fleeting moments in the daily life of everyday Black Americans. The couple in As American as Apple Pie (2020), one sporting a denim jacket and chinos, the other flaunting a rose-coloured skirt and T-shirt that reads ‘Barbie’, pose before a vintage car, a yellow house and a white picket fence. In What’s different about Alice is that she has the most incisive way of telling the truth (2017), a woman with a shy smile holds a Pentax film camera close to her chest, adjusting its lens with a manicured hand. In their midst, a grand and enigmatic triptych titled Ecclesia (The Meeting of Inheritance and Horizons) (2024) transports viewers out of the ordinary world of picket fences and Alices with cameras into an ambiguous and surreal setting inhabited by unknowns. Composed of three large panels with rounded tops, each containing a lifesize figure gazing out from a copper-roofed tower, this oil on linen triptych showcases the complexities and idiosyncrasies within Sherald’s typically bold and clearcut visual language.

Sherald’s triptych is at once spiritual and secular. The artist was born in Columbus, Georgia, and, according to interviews, grew up practising Christianity. Although she is no longer religious, the influence of her upbringing lingers in her work: ‘ecclesia’, after all, is a word that refers to an assembly of Ancient Greek citizens, which the New Testament translates as ‘church’. For that reason, and because of the triptych’s strong historical ties to Christian art, as a format often used in medieval and early modern altarpieces to organise images of religious personages and biblical scenes, the trio in Ecclesia come across as contemporary deities or saints. Despite being dressed in everyday attire – a graphic tee, a patterned sweater vest, a rainbow sundress – they don’t behave like everyday people. Squinting in the bright daylight, the three of them appear to be waiting, with varying levels of excitement and scepticism, for the arrival of a person or phenomenon in the distance. Rather than ‘confronting’ viewers, as Sherald’s sitters are often said to do, these figures seem engrossed in something other than – and perhaps more profound than – intercepting our demanding stares. The artist gives no indication of how long they’ve been in their towers or how long they’ll stay.

Ecclesia is not, to be sure, merely a reproduction of canonical Christian art that recasts white European personages and symbols with their Black American counterparts, were that even possible. How, for instance, would one interpret the metal marine-animal ornaments on the weathervanes that adorn the three towers in the vein of Christian teleology? The sperm whale in the central panel may allude to the Book of Jonah in the Old Testament; the tortoise and dolphin in the other sections, though, are not explicitly mentioned in the bible. These ornamental forms, which exude the tawdriness of beach souvenirs, bring Sherald’s metaphysically titled composition back down to earth.

The architecture, too, looks rather secular. We have three boothlike enclosures that resemble a cross between lifeguard stands and cupolas on stilts; they’ve been painted a uniform white and outfitted with simple Dutch doors, out of whose windows the three figures lean. Notably, the towers are so high in air that no horizon line is visible. In interviews, Sherald cites an image of a phonebooth in Wes Anderson’s film The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) as the inspiration behind these edifices. One can see how Sherald melds the quirky romanticism of Anderson’s cinematic language – his planimetric compositions, his two-dimensional characters, his love of symmetry – with her own medley of the visual motifs. In this sense, her jaunty tortoise and handsome dolphin call to mind how one of the characters in The Grand Budapest Hotel, Agatha, has a birthmark shaped like Mexico on her right cheek, an attribute that proves inconsequential to Anderson’s plot. Similarly in Ecclesia, forms point behind their backs to cultural associations that serve no practical purpose in the composition. The atypical symbols or near-symbols in Sherald’s triptych inject just enough instability into the scene to make one wary of the fair weather and spotless facades.

Part of Ecclesia’s capriciousness as a set of images also lies in its awareness of itself as a mélange of carefully constructed illusions. Sherald conspicuously subverts naturalism by pushing everything in the picture plane up to the foreground and rendering the architectural elements in a flat, graphic style. Despite insinuating a bit of depth inside the booths, where her figures stand, Sherald chooses to leave out the back legs of the towers at the bottom of each panel. Meanwhile, she has the windows in the Dutch doors double as frames within frames, which attempt but ultimately fail to contain her sitters’ bust portraits within their ruler-straight lines.

Because the surfaces of the paintings are in a sense as flat as the museum walls, the negative spaces between the panels eventually start to resemble the columns of an arcade, behind which is spread an unbroken expanse of Magritte-blue sky. It is possible, in other words, to imagine that the three figures occupy the same physical plane. Even so, though, they appear aloof to each other’s existences. Their condition reminds me of a poem I keep seeing on the New York City subway, by the Indian American writer Srikanth Reddy. Titled ‘Everything’ (2004), it describes a man and a woman engaging in fanciful activities – she watches a solar eclipse, he finds a kite in the woods. The reader is made to anticipate the convergence of their lives, but at the end, Reddy writes, ‘They did not meet, / so they could never be parted’. Likewise, in the quiet, stalwart gazes of Ecclesia’s trio of protagonists, one sees intimations of the lives of saints who may have lived centuries apart, or actors trying out for the same role, unbeknownst to one another. It is not so much that the figures seem united in a common cause or indoctrinated in the same belief system as they just so happen to be oriented in the same direction. Whether their paths will, metaphorically speaking, converge or continue in parallel remains to be seen.

Ecclesia (The Meeting of Inheritance and Horizons) is on view in Amy Sherald’s retrospective American Sublime, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, through 10 August

From the May 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.