On the top floor of the Reunification Palace in Ho Chi Minh City, in what was once, 40 years ago, the South Vietnamese president’s personal suite, a series of animal skulls, gifts from foreign leaders, hang from the wall. Coming across these remains during a visit to the palace upon commencing his residency at Sàn Art, Nguyen Tran Nam saw in them the very essence of the trophy; its sanguinary core.

In a sense the palace itself has become just such a trophy, its furniture and fittings preserved – as if in aspic – since the North Vietnamese tanks rolled into the palace grounds in 1975. But it was a symbol from the historical museum in his hometown of Hanoi, a relic of French occupation later put to bloody use in the South during the American War, that Nam chose as the key signifier around which his works for this installation circulate: the guillotine.

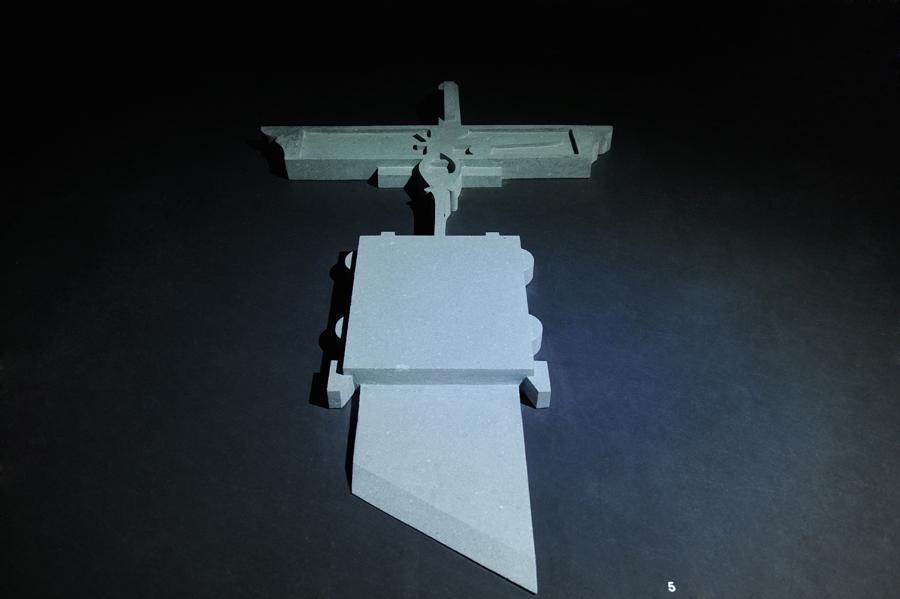

In a room darkened as if for the display of ethnographic treasures, the floorspace is dominated by a 120cm-long granite sculpture, reworking the guillotine’s blade into a kind of religious iconography (A Part of the Structure, all works 2014). In a small display case hung on the wall, a like image of the executioner’s tool, its mechanism simplified into something between an Egyptian ankh and an American military medal of honour, is rendered in tin, small enough to be pinned to the breast of a uniform (Like a Variant). Between these two icons, death becomes both monument and commemorative badge.

As if to nail the point, a vitrine at another wall contains three small rough-hewn mounds: one of stone, one of tin and a third composed of the artist’s own congealed blood (Endless Loop). History is made not only of the first two.

Another room, containing the work of HCMC resident Pham Dinh Tien, is stuffed with images of aircraft, inspired by Malaysia Airlines flight 370, whose disappearance last spring coincided with the beginning of Tran’s residency. But the first thing to catch one’s eye is a video triptych (Yesterday). All three frames appear at first to contain the kind of drifting cloud images you might acquire by pressing your smart phone to the window of a jumbo jet. Closer examination reveals something more sinister. On the left: a baby’s head, modelled on a found image of MH370’s youngest passenger; in the centre, a sugar cube at 1/35th human size; and on the right an aircraft. All three are modelled in sugar, slowly dissolving in water: a haunting image of the transience of existence.

On the floor, more planes; 16 of them this time in chrome-plated plastic, flying in diamond formation (When). Again, it’s only with a closer look that we catch what is so unsettling about this work: the strangely fleshy armature of the jets. Like something out of a David Cronenberg film, these aircraft seem to be formed of muscle and bone, their aerodynamic sheen suddenly revealed to be as tender and vulnerable as we are. The accident, as in the philosophy of Paul Virilio, then seems to be inevitable, encoded in the design. Another ‘endless loop’ besides Nguyen Tran Nam’s: along with the impermeable hard surfaces of history, its flesh and blood.

This article was first published in the April 205 issue.