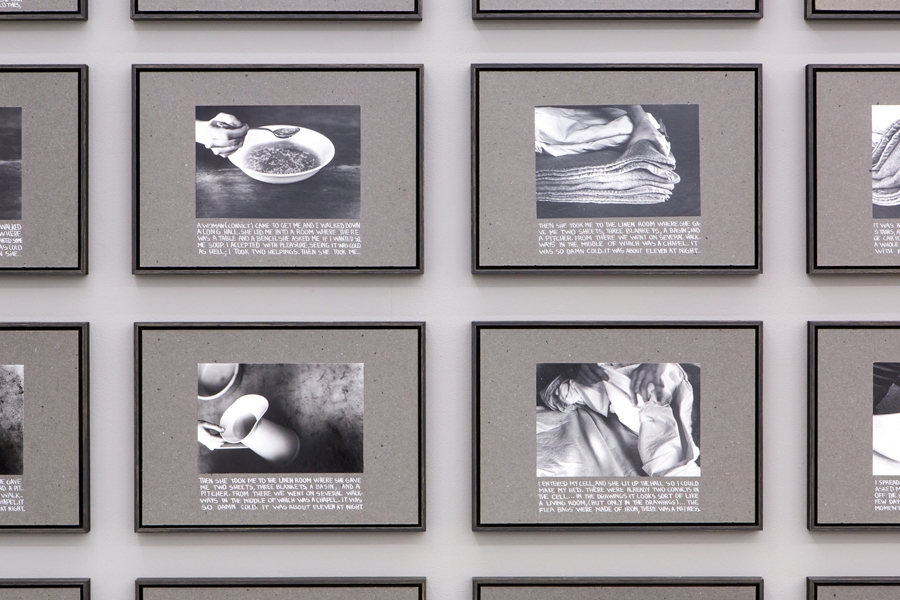

Nil Yalter’s installation La Roquette, Prison de Femmes (1974, in collaboration with Judy Blum and Nicole Croiset) presents the testimony of a former convict in France’s once-notorious women’s prison – and initially it resembles a relatively straightforward, sociological-style display. There’s a video with a voiceover that describes the routines and rituals of incarceration; on the wall behind are grids of panels containing monochrome images and handwritten texts that, together with a folder you can flip through, give shape to more detailed episodes: the woman being instructed to strip on arrival, for instance; or being given a sackcloth dress to wear; or sharing a cell with an evident pyromaniac. So far, so typical – and so grimly dispiriting.

Certain aspects, however, stand out as altogether more curious. One panel tells how the prisoners would eat pictures of salads, chicken and other meals snipped from recipe magazines, as a substitute for the real thing. And there’s a parallel kind of substitution, a sort of confusion between differing levels of representation, in the work’s very structure – with the panels on one side all featuring photographic images, while those opposite have been translated into naive, slightly clunky drawings. Even more jarring are the occasional moments where the accompanying texts bizarrely repeat across successive panels, like a sort of narrative stutter or glitch.

Gradually, the sense develops of some kind of semiological slippage having occurred, of the usual workings of signification fraying at the edges – so that signs sometimes get treated as things; and conversely, things become signs, as when the prisoners write messages in pen across their bodies. Indeed, the longer you spend with the installation, the more complex and contradictory it seems – both presenting an ostensibly factual, documentary account of prison life while revealing those documents as somehow flawed, or merely aesthetic constructs.

All of which means that while Yalter is often characterised as a feminist artist, it’s really quite a different sort of feminism compared to that of many other female artists who were working during the 1960s and 70s. Looking around this first London show of her work, with its small selection of early pieces, it becomes clear that her main concern is less with representing marginalised perspectives than it is with problematising the nature of representation itself, upsetting the certainties of any one, single perspective.

Nor is her focus purely on female identity. As a Turkish artist based in Paris (where she continues to live and work), much of her practice deals with concepts of ethnicity and migration. In Rahime, Kurdish Woman from Turkey (1979) – the other large, multipart installation here – the eponymous subject swaps the poverty and political violence of her rural upbringing for a different kind of oppression in the slums of Istanbul. Again, though, the video, photographs and drawings serve to undermine any sort of totalising perspective, offering only fragments, differing versions, recursive variations. And these sorts of ideas reach their apogee in a third work, Harem (1979), a long, meandering, but oddly captivating video based on accounts of concubines working in an Ottoman palace – and whose climactic scene involves an appallingly gruesome description of a eunuch’s castration. Such barbarities, the voiceover declares, “correspond to the absurd logic of a despotic and decadent power” – and also, by implication, to the logic of a single, centralised perspective, brutally reordering the world to its sole satisfaction.

This article was first published in the April 2015 issue.