Documenta 14, various venues, Athens, 8 April – 16 July

various venues, Kassel, 10 June – 19 September

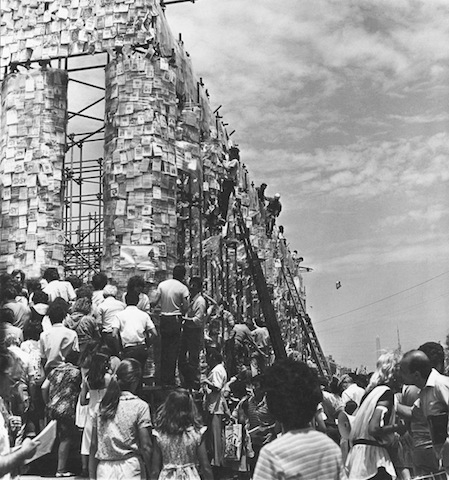

Sixty-two years ago, Documenta was initiated as a subsection of a horticultural show in Kassel, with the aim of ‘documenting’ the so-called degenerate art banned during the Nazi era. The quinquennial event, now a coronation ceremony in any curatorial career, has come a long way since; indeed, this time, directed by Adam Szymczyk, it has come 2,489km. That’s the distance from Kassel to the Greek capital, where the first portion of the two-part 14th edition, which is subtitled ‘Learning from Athens’, will open, thoughtfully timetabled ahead not only of Documenta’s Germany-based remainder but also of Skulptur Projekte Münster and the Venice Biennale. The Kassel/Athens twinning, Szymczyk has suggested, reflects the urgency of looking at extremes within the precarious European Union: surplus-running and dominant Germany, destitute and dominated Greece, and creating some kind of symbolic exchange and interface between them.

One example of that will be the presentation, at Kassel’s Fridericianum, of works from the collection of Greece’s National Museum of Contemporary Art. Otherwise, though, working in Athens has clearly not been easy, despite a vigorous runup involving piggybacking on Greece-based art magazine South as a State of Mind and ‘emergency cinema’ posted weekly on Documenta’s website by anonymous Syrian filmmaking group Abounaddara. A month out, only the aforementioned two institutions were confirmed as exhibition venues, and organisers’ lips were sealed concerning the list of artists. It does appear permission has been given for the use of Athens’s public squares, and for a horseback parade at the opening, relating to the equine procession on the Parthenon frieze and launching a pointedly border-crossing 100-day horseback journey up through the western Balkans to Kassel. If Documenta 14 ends up unpredictable, unbalanced and disruptive, it’ll at least mirror these times.

Sadie Benning, Kunsthalle Basel, through 30 April

In Szymczyk’s previous workplace, the Kunsthalle Basel, there’s currently more evidence of the exigencies of politics, this time from an American perspective. In the artworld, Sadie Benning is best known for videos, made since her teens during the late 1980s and including early PixelVision experiments, which explored sexuality and the travails of youth and were laced with pop-cultural tropes, while in the music world she’s known for cofounding feminist band Le Tigre. But her exhibition here, Shared Eye, whose title evokes the collaborative nature of seeing and creating meaning, represents a swerve of sorts, applying a montage aesthetic to 55 so-called paintings – actually photographic reliefs accoutred with shelves containing little toy figures, grandfather clocks, etc, and including painterly Aqua-Resin elements and found photographs, the imagery traversing the last half-century. Among the elements are protesters, Ku Klux Klan marchers, Benjamin Franklin (on a banknote), Benning’s vinyl collection at home – in sum, ‘a highly personal response to the state of the world at a moment of deep political uncertainty’, says the institution, ‘imbued with the charge of what has come before and what is yet to come’. Its very in-between-ness, you might recognise, is apropos.

Linder, Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm, through 22 April

Collage is a format that invites renewal because it’s a century old, originating in Cubism and finessed by German practitioners such as John Heartfield and Hannah Höch. One of their ablest spiritual descendants is Linder, who’s made disruptive feminist collages for four decades, typically emphasising the female body and often repurposing porn and interior design. In her first solo with Andréhn-Schiptjenko (and first exhibition in Scandinavia), nude women appear half-covered with swarms of butterflies and shells, and smeared with cosmetics; or oiled and given toothy, lipsticked mouths for nipples, clothes-irons for heads and artwork titles referring to the Buzzcocks. (Linder, in graphic-designer mode, created the nipple-mouth-iron combo for the sleeve of the band’s 1977 single Orgasm Addict; as the frontwoman of Ludus from 1978 to 84, she was a doyenne of UK postpunk in her own right.)

If, as the gallery says, ‘institutionalised misogyny’ is her bête noire, her art can never be ill timed. Given the current unravelling of progress towards gender parity – the threatened rollback of women’s reproductive rights in America and legal protection against domestic violence in Russia – it looks doubly relevant now.

Vija Celmins, Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, through 15 April

If such shifts are another sign of reality currently being off the rails – or, as a recent New Yorker article half-jokingly had it, that we’re living in a computer simulation gone wrong – what might offer some balm? Maybe a Vija Celmins exhibition. Now in its final couple of weeks, the artist’s first New York exhibition in seven years and first solo show with Matthew Marks is a 19-work excursion through the Latvian-born outlier’s quasi-mystic photorealism, her endlessly magical conversion of photographs depicting a single frozen moment into drawings with cosmic weight and transporting precision – star fields, oceans – and uncanny excursions into sculpture. (Eg real stones accompanied by painted bronze replicas.) All of this, Celmins has said, is rooted in her own life, or her own practice: getting the deepest black from a pencil for her night skies, wandering around on piers or in deserts. She said as much to an interviewer once, and then added, ‘that’s enough, for goodness sake’. It is.

Dee Ferris, Corvi-Mora, London, through 19 April

Over a decade or so in which she’s flown somewhat under the radar, Dee Ferris’s paintings have progressed from stenographic traces of landscape to blotchy, shadowy pastel abstractions, to something like Water Lilies-era Monet with the lilies left out. Yet quite consistently they’ve presented themselves as gauzy painterly arenas less concerned with physical space than inner space. Sometimes, as drink- and drug-slangy titles like Candy Flipping on a String and Half Cut (both 2009) might suggest, it’s an altered state; generally it’s sybaritic, as witness Love Hotel (2007) or Lounge Lover (2013); and occasionally Ferris’s greys and greens imply morning-after nausea. In her fourth exhibition at Corvi-Mora, Pictures of Trickery (whose title quotes lyrics from a song by Goth trailblazers The Cure), the Somerset-born painter continues to drift away from figuration into abstraction, as if enacting a long dissolution. In the selection of new work we’ve seen, the forms in her compositions resemble crystals or precious stones but increasingly collapse into brushstrokes. It doesn’t seem by chance that some of these, as they bond together, also look like cigarettes.

Michel François, Xavier Hufkens, Brussels, through May 6

In his 2002 video Self-Portrait Against Nature, Michel François strolls, smoking, across a concrete floor while wine bottles fall around him, creating an aleatory smashed-glass composition. Chance, in the Belgian artist’s work, is a regular protagonist: he’s based loopy metal sculptures on scribbles by stationers’ customers testing pens, made blown-glass sculptures advertising his lung capacity at that moment, filmed an inchworm traversing a world map. There’s something roguish in these proposals; their meaning feels contingent, and they often delegate physical effort. Fitting, then, that François has repeatedly linked art and criminality: a block of polystyrene taped to the wall was inspired by a convicted smuggler’s attempt to conceal drugs; a later series of photographs depicted trial evidence, the objects’ value – as ‘Exhibit A’, etc, and then later as exhibits – impishly unfixed. Since art, under these auspices, is a game whose rules are for breaking, we’re guessing what François will show in Brussels by looking at the things he’s already made and excluding them as possibilities.

Seth Price, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 15 April – 3 September

The idea of Seth Price having a retrospective, and a full-dress one like Social Synthetic at that, is slightly weird, since the Palestine-born American artist isn’t naturally associated with looking back. His mutating essay Dispersion, first published in 2002, influenced his peer group by positioning art in the digital era as a continually metamorphosing, frontward process; his artworks, meanwhile, reflect plasticity and, relatedly, the pressures of modernity on the body and the self. (See Price’s vacuum-formed plastic shells of bomber jackets from 2005–8, once-utilitarian items later co-opted by the fashion industry, and his conversion of the negative space on a jpeg between ‘two people engaged in intimate action’ into a wall-based sculpture.) One might wonder how the Stedelijk will accommodate his overflow of extramural works, from mixtapes onward, but since the 140 works on display include ‘sculpture, installation, 16mm film, photography, drawing, painting, video, clothing and textiles, web design, music and sound, and poetry’, evidently they’ve found a way.

Dirk Stewen, Gerhardsen Gerner, Berlin, through 20 April

Dirk Stewen’s way, over the past decadeor so, has consistently involved gazing towards the past, and doing it via works on paper. Within that circumscription the Dortmund-born artist has found freedom a plenty, accessorising his inventively elegiac works with thread, pins, confetti, streamers, tickertape and old photographs. For his current exhibition, Stewen has decided to ‘spice up’ – his words – the show with someone else’s paperwork: expect, interspersed with his art, sanctioned pages from Gay Goth Scene, a queer zine put together by singer/songwriter Joel Gibb (of the Hidden Cameras) and artist Paul P. (Goths, alert readers will note, are a sub-theme of this month’s column.) And, generally, in his seventh show with Gerhardsen Gerner, once again we’re being rewound through Stewen’s autobiography: the zine, he says, reminds him of his own gothy upbringing in ‘a small industrial town in Germany, feeling doomed’.

Steven Claydon, The Common Guild, Glasgow, 22 April – 9 July

The past in Steven Claydon’s work is less another country, more another dimension. The party line on his artworks is that experiencing them is like being an alien visitor trying to understand the earth from an archaeological dig; more generally, though, they’re meditations on the diversely fluctuant status of objects. ‘Jeopardy and pressure’ are stated watch words for his Common Guild exhibition, which ‘plays out the processes whereby objects come into being, accrue meaning, and endure and transform through environmental and cultural shifts’. For what that means in practical terms we might look to Claydon’s last exhibition at Kimmerich in Berlin, where sculptures fused circuit boards and fragments of sculpted bodies, thermal images, terracotta, mesh, cuneiforms and cables in atmospheric assemblies that seemed to span centuries and civilisations.

Giulio Paolini, Galleria Christian Stein, Milan through 29 April

Fifty-one years ago, under the pseudonym Christian Stein, Margherita von Stein opened a gallery in Turin that would become a driver of the Arte Povera movement and of advanced Italian art more generally. At the end of 2016, some 250 exhibitions later, the gallery – now based in Milan – made an appropriate gesture to its half-century birthday with a 19-work, two-venue show, spanning 1972 to 2016, by one of Italian conceptual art’s leading lights (and one of the gallery’s longstanding collaborators), the Turinese Giulio Paolini, always an outrider in Arte Povera due to his fascination with art history. Mimesis (1976–88), for example, involves two plaster copies of a classical sculpture facing each other; the intention, he’s said, being ‘to capture the distance that separates them and the void that the work creates around itself, taking away from us the right to possess its impenetrable gaze’, while the new work Fine (2016) is a sort of raft, referencing a Watteau painting and containing myriad tools, parts of artwork and other extracts from the artist’s studio. After its half-year run, the exhibition closes at the end of this month. Now in his mid-seventies, Paolini – tools restored, out of excuses – will have to get back to work.

From the April 2017 issue of ArtReview