“This is shit,” the man in the ski jacket spat. “It’s fucking propaganda.” A moment earlier he had burst into the gallery and demanded I tell him what the charcoal drawings I was looking at were about. “Er…,” I said hesitantly, “They each depict an arson attack made on a building in which asylum seekers were housed.” It became evident that ski-jacket-man thought I was the artist. “I could fill this room with drawings of attacks made by immigrants on Swedes. Why don’t you show that?” “Really?” I asked. “Yes,” the man said, adding, by way of curious evidence, “I’m Swedish.” With that, he stormed back out into a Baltic snowstorm, shouting over his shoulder, “You’re a communist. A dirty fucking Trot.”

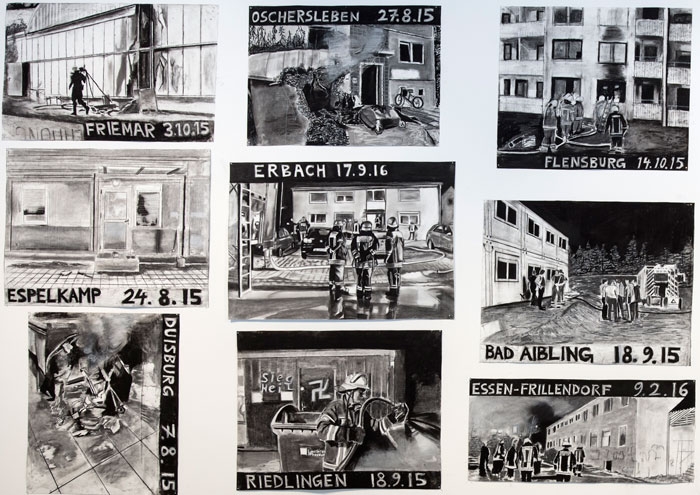

Thomas Kilpper’s Burnout (2016–17) is one of the more forceful works in this group show, curated by Katerina Gregos, which takes as its focus the nation-state, nationhood as a cultural construct and the rise of nationalism, and occurs in the centenary of the Estonian republic. Naturally, such a subject leads to questions of who is welcome (or made to feel welcome) in a country, and who is not (who is ‘of the culture’, and who is not). At its best the exhibition delves into this thorny topic with considerable nuance; at worst, it hectors. In the latter category, Daniela Ortiz’s ABC of Racist Europe (2017) is a series of 26 collages with accompanying captions. ‘A’, for example, is for this: ‘The airplanes that white European tourists take on their holiday are used for the deportations of racialized migrants and asylum seekers’. ‘M’ is for the Mediterranean, and so on, each of the Peruvian-born, Barcelona-based artist’s instalments proving angrier and more condescending in their political simplicity than the last. It makes me wonder about the work’s intent: I get that Europe has a lot to feel guilty about, but these are just Woke-101 bullet points.

Loulou Cherinet’s two-channel video Statecraft (2017) also riffs on immigration, but removes the singular voice of the artist (which holds a place of privilege in a gallery) and addresses the subject through members of the (Swedish) public. In a series of discussion circles, featuring a multitude of political standpoints, the concepts of innanförskap (‘insidership’) and utanförskap (‘outsidership’) are interrogated. We hear both from migrants who wish but are denied innanförskap (even if they have become Swedish citizens ) and from those resistant to immigration. The thoughtfulness demonstrated in these conversations is in stark contrast to Ortiz’s grandstanding, as the speakers wrangle with the importance of having a national identity and the implicit discrimination that comes with it. This is echoed in Jonas Staal’s ambitious, ongoing New Unions conferences, represented here through video documentation presented in a room carpeted with a map of Europe, in which representatives of various independence movements (from the Scottish National Party to a Kurdish solidarity group) come together to discuss methods of transnational solidarity, and how nationalism can be radical, socially liberal and outward-looking.

The exhibition, its title an inversion of art historian Jacob Burckhardt’s maxim, is evenhanded in its profiling of what might be termed, respectively, positive insidership and toxic insidership (for his part, Burckhardt would see both as suffocating modes of control). Vexillology (2015), 211 photographs found on the Internet by Cristina Lucas, of football fans decked out in the colours of their national teams, demonstrate instances of the former approach; so does Jaanus Samma’s investigation into the Estonian folk culture lost under the Soviet occupation (embodied through a display of traditional straw costumes and archive photographs of them in use). Conversely, there’s Szabolcs KissPál’s From Fake Mountains to Faith (Hungarian Triology) (2016), a faux museum-display that traces the folkloric myths currently being deployed in Hungarian extreme nationalism. My ski-jacketed pal might have liked, without irony, the relics on show in KissPál’s work – I can imagine him waxing lyrical on the mystical significance of the Turul bird to his political brethren in Hungary – but he’s never going to be persuaded from his poisonous path by the majority of the works here, propaganda or not.

The State is not a Work of Art at Tallinn Art Hall, 16 February – 29 April. From the April 2018 issue of ArtReview