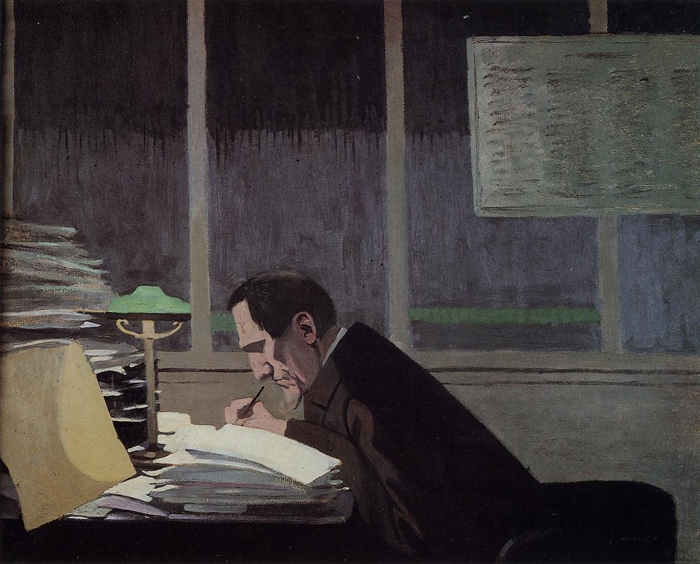

The critical scope of Félix Fénéon (1861–1944), to whom we owe the first recognition of artists such as Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, the Postimpressionists and French avant-gardes through to Surrealism, is currently being celebrated by two major French institutions – the Musée d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie and the Musée du Quai Branly. Féneon wrote little, but as an editor (he edited Arthur Rimbaud, Stéphane Mallarmé, Oscar Wilde and James Joyce), curator, anarchist and friend of artists, he was nevertheless able to produce the critical environment necessary for these artists to be seen, contextualised and understood. This is the fundamental work of criticism: not to judge art from a position of superior authority but, more complexly, to produce the critical horizon within which the artwork becomes intelligible.

Critical discourse establishes the space within which the artwork can realise its full potential. That discourse is firstly that which takes place in art periodicals and catalogues. It is critical discourse that allows the artwork’s identification, recognition and inclusion in the artworld. This social function is all the more important because globalisation, decolonial and postcolonial questions and feminist, queer and trans revolutions have torn up the old critical maps and brought new ways of conceiving and practising art. This transformation is so truly international that, in the space of three decades, art criticism has completely reinvented itself in its methods and arguments, drawing its resources from philosophy, anthropology, the humanities, social sciences and ‘hard’ science, as much as from activist texts and militant actions. The corpus of critical texts has been greatly enriched, testifying to ‘conversations’ taking place across five continents, freed from the traditional demarcations of art and nonart, while increasingly taking into account many visual aspects of political and social phenomena.

Criticism is no longer simply a question of establishing genealogies or frameworks; it’s a question of accompanying those dynamics that demand the ongoing reconstruction of critical language. Critical tools are never fixed, but need to be continuously reconfigured. This is a far cry from the ‘sovereign judgments’, rankings, comparative evaluations and other kinds of taxonomies imposed on artists, which are still often imagined as the normal function of the ‘influential’ critic.

In a globalised, neoliberal world, even supranational megagalleries understand this. Those exquisite publications devoted to the artists they represent are no longer only luxurious objects but are replete with an impeccable scholarship that the galleries are ready to finance. Museums, like universities, are the guarantors of these new standards, their editorial rigour an essential part of the artworld ecosystem.

But French public institutions haven’t understood this. Rather than being part of this ecosystem, they present themselves as models of excellence, while excusing themselves from the responsibility of properly paying those on whom they call to write their publications.

For example, the Centre Pompidou, the Réunion des Musées Nationaux and the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris currently pay between €40 and €46 per page (roughly 250 words). For each essay – about a month’s work – writers can expect a fee well below the minimum monthly wage, which, in France, means they cannot qualify for social security for artists and authors.

To turn intellectual work (an ensemble of competences including research, writing, graphic design, curating) into an ever more shrinkable item on your budget sheet (where shipment, insurance values and pr are not reduced) is to mark it out as superfluous. As a result, you end up excluding yourself, in effect, from transnational relations of power. A work cannot be seen, let alone exported, without critical validation. The agents of this validation are neither the auction prices nor the purchases of famous collectors, contrary to what some believe. What ensures the reception of artworks is that they are shown, scrutinised, analysed, commented on; that they gradually enter into the conversations of their generation and of following generations. An artwork that has no value other than market value cannot go down in history.

It should come as no surprise, then, that French artists have almost disappeared from major international exhibitions (including Documenta), as well as from the few dozen biennials that really matter around the world (with Venice, built around national pavilions, being the exception). This absence is not due to a ‘decline of the French scene’ but to the suppression of all points of critical mediation that are essential to the international accreditation without which an artist, a group or a collective cannot become visible outside of France. Those whom we might cite as counter-examples (such as – for example – Pierre Huyghe or Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster) are those who, by contrast, have been able to acquire a strong critical ‘passport’.

The precarity of intellectuals in the artworld is all the more obscene given the amount of money that flows through it. It gives the impression that criticism is not a livelihood but a bourgeois pastime (or one for bourgeois women, according to a well-established sexist tradition), a luxury. The terrain thus appears to be booby-trapped for future generations of critics, on which new generations of artists will rely.

It is not enough to lament the much discussed ‘end of art criticism’. It is necessary to take stock of its crushing effect on French society: it is the reduction to silence of a whole generation of artists and intellectuals that is at stake here. Some of them have taken matters into their own hands (for instance W. A. G. E. in the United States, Wages for Wages Against in Switzerland, ‘les vagues‘ or La Buse in France). More important, as in the theatre circuit (which seems to know better – at least in France – how to make these voices heard), these are collectives that not only demand to be able to make a living from their work, but have been able to associate these demands with that of a better representation of women, racialised people, trans and nonbinary people or disabled people. And this issue – the fight against all discrimination – is inseparable from the critical horizon for which we are fighting.

Elisabeth Lebovici is an art historian, journalist and critic, and Patricia Falguières is a professor at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales, both based in Paris. This text was originally published in French in Libération

From the December 2019 issue of ArtReview