At the beginning of this year, the Conservative leader of the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead (it’s in England, in case you hadn’t guessed) demanded that police exercise whatever legal powers might be at their disposal to clear the local area of homeless people in anticipation of the upcoming royal wedding at Windsor Castle. According to Councillor Simon Dudley, ‘an epidemic of rough sleeping and vagrancy’ was blighting his ‘beautiful town’. He went on to conjure images of beggars frogmarching tourists to cashpoints and imply that visible poverty was an offence to royal and tourist eyes. Indeed, underlying all this is the suggestion that Dudley (and a great many others like him) believe poverty to be a choice rather than an imposition, a matter of behaviour rather than circumstance, and therefore a matter for the police rather than local councils (with whom, incidentally, responsibility for the provision of housing in England rests).

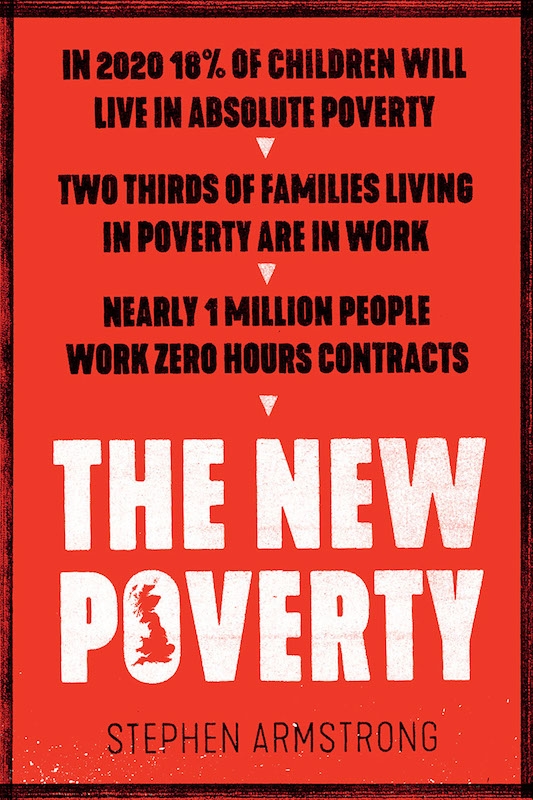

The increasing abandonment and demonisation of people who are in need within British society is the subject of journalist Stephen Armstrong’s new study of contemporary poverty. Published at the end of 2017, which marked the 75th anniversary of the Beveridge Report (which paved the way for the establishment of the United Kingdom’s welfare state), it looks at the ways in which the nature of poverty has changed in recent times and how social-support mechanisms designed to combat poverty are either failing to do so or are making the problem worse. Today two-thirds of families living in poverty are in work, albeit on zero-hours contracts or worse. For many, the value of work and the cost of living simply don’t match up. The age of the post-Beveridge welfare state may have reached its end, says Armstrong, but Beveridge’s five ‘Giant Evils’ – want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness – are returning.

To experience poverty, Armstrong argues, is to experience injustice: poverty is unfair. And in an age when people like Dudley, and the mass media in general, have linked words such as ‘benefits’ with ‘cheat’ and ‘fraud’, language matters. So Armstrong takes us on a tour of phrases like the ‘poverty premium’ (things cost more when you have less, because the discounted options – online offers, advance payments, etc – are out of your reach), the ‘digitally deprived’ (those without access to an on-tap online connection in an age in which social services are increasingly online), the ‘democratic deficit’ (the closure of local newspapers, for example, makes it harder for local people to be heard and, according to analysis, leads to lower voter turnout because the issues at stake seem not to involve them) and the rise of ‘DIY dentistry’ (it’s simply cheaper). Context is important too: benefit fraud amounts to £1.3 billion per year; the tax gap (between what’s owed in taxes and what’s paid in taxes) for 2013–14 was £34b. It’s generally more popular to make a show of punishing the former rather than tackling the latter.

‘The UK is fragmenting into enclaves,’ Armstong writes, ‘divided by income and attitude, and we are no longer listening to each other. The consequences can be devastating for all of us.’ The sense of resentment that leads to Brexit is just one of them.

Like all good journalists, Armstrong mixes hard facts with heartbreaking interviews, deploying the latter to give weight to the former and to make their abstractions more devastatingly real. In all this he is informed by George Orwell’s groundbreaking 1937 survey of poverty in the north of England, The Road to Wigan Pier (which Armstrong updated, as The Road to Wigan Pier Revisited, on the 75th anniversary of its publication). Having completed his study, Armstrong notes, Orwell stopped writing and started fighting for what he believed in (during the Spanish Civil War).

It’s stirring stuff, and if ever there was an issue that deserved to have the much-abused ‘urgent’ appended to it, this is it. The rich are getting richer, the poor are getting poorer: a definition of injustice that goes back, via Karl Marx and US President Andrew Jackson, almost 200 years. Much of the problem rests on questions of access. Of people who are left behind by digital revolutions (people that contemporary art, seemingly constantly celebrating a postdigital age, also too often ignores), house prices and the cost of healthcare, for example, and the corporations and governments that remorselessly drive those things on. Read this and you’ll realise that now is our time to act.

From the January & February 2018 issue of ArtReview