Only a handful of newspaper comic strips have transcended their status as ‘funnies’ and come to be regarded as significant works of art. George Herriman’s Krazy Kat (1913–44) and Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland (1905–26) are probably held in highest esteem; but up there too is Charles M. Schulz’s Peanuts (1950–2000). Of course, compared to anything else in the canon, the reach of Schulz’s creation is unsurpassed – both in terms of the strip itself (the complete Peanuts consists of a staggering 17,897 episodes, and at its peak was syndicated across over 2,600 newspapers worldwide) and its broader cultural presence, from being developed into numerous TV series and movies, to the seemingly endless opportunities for mass merchandising.

Good Grief, Charlie Brown! contains various teeming displays that show off the vast range of licensed products – toys, lunchboxes, stationery, clothing – most inevitably featuring the strip’s breakout star, Snoopy. More interesting, though, are the unofficial appropriations, the patches for example that US servicemen in Vietnam wore combining Peanuts imagery with drugs and sex references, which give a better sense of the characters’ ubiquity, along with the many admiring letters written to Schulz by figures ranging from Timothy Leary to Ronald Reagan. As for the strips themselves, there are scores of originals throughout the exhibition, usually demonstrating the social relevance of Peanuts – the irascible, independent character of Lucy, for instance, linking to debates around feminism, as well as to Schulz’s suspicion of psychiatry (one of the strip’s best recurring gags was that Lucy, the loudmouthed manipulator, also dispensed psychiatric advice). Not that Schulz’s characters were mere ciphers. What’s remarkable about Peanuts is how it managed to depict a viable, functioning world, one shot through with a distinctly downbeat, melancholy tone, even as its only visible actors happened to be children – or, as Umberto Eco, one of the first cultural commentators to seriously consider Peanuts, called them, ‘monstrous, infantile reductions of all the neuroses of the modern citizen of industrial civilisation’.

All of this, which might be called the content and context of Peanuts, the exhibition is excellent on. It’s less good on the strip’s form, its visual properties. Sure, a couple of sections focus on Schulz’s drawing technique, and there’s a fun film portrait of him deftly sketching. But in a show predicated upon the idea that comics are worthy of artistic consideration, some deeper analysis – how Schulz’s style progressively became starker and shakier, say – would have been welcome. After all, it wasn’t just mainstream culture where Peanuts’ influence was felt, via fads such as the jocular ‘Snoopy for President’ campaigns, but within comics themselves as a medium. Peanuts’ impact on later works, whether newspaper strips like Calvin and Hobbes (1985–95) or underground titles like Love and Rockets (1982–), was immense. Yet the exhibition is completely silent on this.

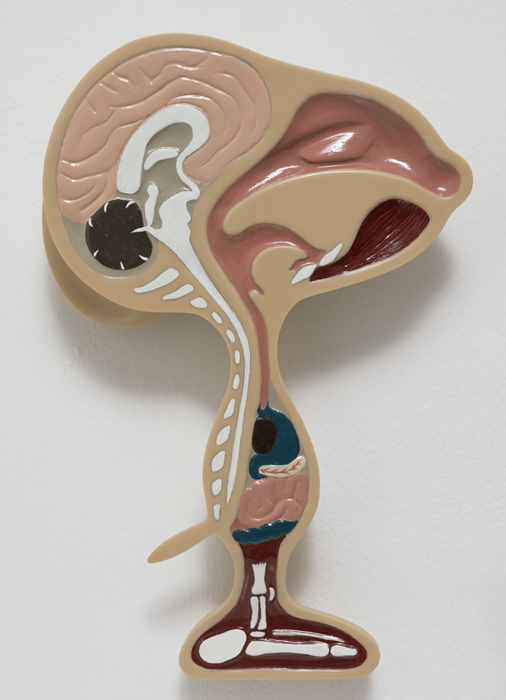

Instead, it turns to contemporary art to make the case for Schulz’s legacy. There are some good pieces: Mel Brimfield’s cartoon, Nuts: Episode 23: Remembrance of Things Past (2018), from her ongoing Peanuts homage series where a Schulz-styled version of the artist pours forth anxieties and vulnerabilities; or David Musgrave’s Animal (1998), an anatomical sculptural model of a bisected Snoopy – works that are effective precisely because they engage with Schulz’s creation on a formal, albeit ironic, level. Too many other pieces, though, give the impression merely of riffing on Peanuts, plundering it for whimsical subject matter – Marcus Coates’s lifesize version of Lucy’s psychiatric booth, Who Knows? (2018), in which visitors can submit ‘life questions’, is the most insipid example. But beyond any individual shortcomings, it’s the reliance on non-comics art as a whole, in order to justify the continued relevance and bolster the intellectual credentials of Peanuts, that feels deeply flawed, and that ultimately undermines the very argument the show sets out to make.

Good Grief, Charlie Brown!, Somerset House, London, 25 October – 3 March 2019

From the January & February 2019 issue of ArtReview