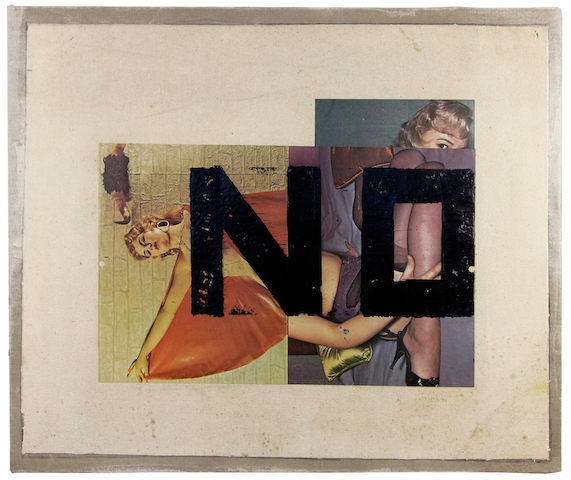

Theodor Adorno famously wrote that ‘after Auschwitz, to write a poem is barbaric’. The failure of attempts to reconcile art and trauma in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust similarly guides multimedia artist Boris Lurie, as this new retrospective of his work demonstrates. Lurie, who died in 2008, was a Holocaust survivor: in 1941 he was deported from Riga, aged sixteen, and subsequently imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps (Stutthof, then Buchenwald) until 1945. Lurie used a number of symbols, including the pinup girl, the yellow star, the swastika, women’s undergarments, sharp knives, archival photographs from concentration camps and, most famously, the word ‘NO’ – part of an anti-Pop, anti-artworld movement spearheaded by himself, Sam Goodman and Stanley Fisher. The show is a single packed room: in one instance, no less than 51 multimedia works either featuring the word ‘NO’ in print, cursive or scrawl, or painted a bright, angry red, are hung in tight columns of seven or more. In a large yellow star installation in the central gallery floor, a number of long serrated knives are forced violently into blocks of cracked concrete.

The next wall is more serene: seven untitled collages, three largescale, four medium-size. Each work shares the same colour scheme, at least from a distance – a bluish-greyish-greenish saturated cutout collage, washed over lightly with white, then spatter-smacked at random with neon orange, red, yellow and pink paint. The whitewashing of the crisp collage leaves the impression of something faded and timeworn – warping picture-perfect smiling children, proud husbands and women as both pinup mistress and doting mother from 1960s advertisements into dredged-up slurry from a murky past.

In one work, a naked woman cut from newsprint kneels in the lower-left corner, posed suggestively. But she’s been decapitated by Lurie’s collaging: a yellow cube of cartoon butter tilts, poised to slide down her body, in a garish union of the salacious and the saccharine. What’s more, the process of making these works – the agent used to bind photograph to canvas, perhaps, or the white paint layer above – has worn down not just the colour but the material of the multimedia collage, rubbing off and rolling away newsprint and shiny magazine paper, decomposing the images in webs of holes and exposing the stitched white cloth of canvas underneath. In this way, the pristine images one could find in any magazine are inverted: they become precious, delicate, fragile. By memorialising the mundane as it crumbles before the viewer’s eyes, Lurie calls the viewer to see the everyday as both sacred and slipping away, in so doing evoking powerful sensations of memory and loss.

In this way, Lurie uses a visual language of iconography popularised by Pop artists and Abstract Expressionists to render legible his trauma, his grief and at times his fury. The exhibition’s curators vacillate between giving no details and, perhaps, saying too much – the works presented come with no individualised wall text or descriptions, save for a series of short paragraphs at the exhibition’s entrance: a limited biography of the artist that includes, almost at random, the fact that the pinups are intended to represent the bodies of female Jewish victims of the Holocaust. Save for this ‘clue’, the viewer is given all of Lurie’s jumbled, manipulated and sometimes mauled hieroglyphs and none of his ciphers, and is thus left with few words, only feelings. Perhaps this reflects the fact that the crux of Lurie’s work defies any single solution; rather, it reflects the chaos of emotions that comes with trying to codify atrocity between the symbolic explanation and the messy truth.

Boris Lurie: Pop-Art After the Holocaust at Museum of Contemporary Art, Kraków, 26 October – 3 February

From the January & February 2019 issue of ArtReview