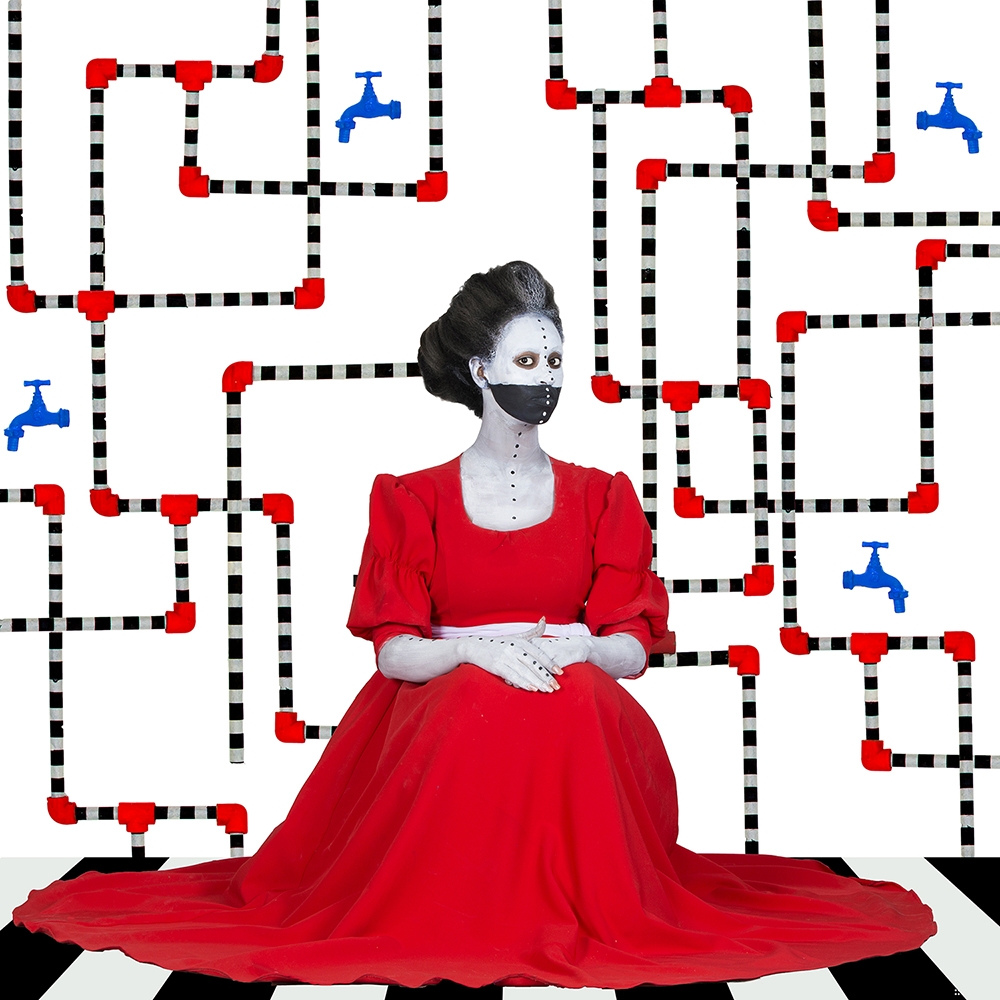

Art in the Age of Anxiety at Sharjah Art Foundation, 21 March – 21 June

‘The age of anxiety’ is a moveable feast. The phrase was initially used to describe the 1920s, but the poetically inclined will identify it with midcentury and W. H. Auden, specifically his eponymous 1947 poem set in a New York bar, rife with angst concerning industrialisation. Last year The Who’s Pete Townshend published a debut novel titled The Age of Anxiety, though we’re not in a hurry to read that. And this year, in Sharjah, Omar Kholeif is repurposing the phrase for Art in the Age of Anxiety, a group show that – in keeping with his curatorial and critical track record – situates the anxious era as our own, tying it to the bombardments of the Internet and digital devices per se. Such a show unsurprisingly finds room for Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Cory Arcangel, Jon Rafman, Cao Fei and Trevor Paglen, but also there are relatively leftfield choices such as Jenna Sutela’s musical film Nimiia Cétïï (2018), which explores ‘consciousness, neural networks and a new Martian language’, and a new iteration of Siebren Versteeg’s big-screen Daily Times (Performer) (2012–), in which, via algorithmic processing, headlines from the UAE-based English-language newspaper are turned into abstract paintings. Meanwhile we look forward to looking back on this era, from the likely hellscape of later this century, as relatively unanxious.

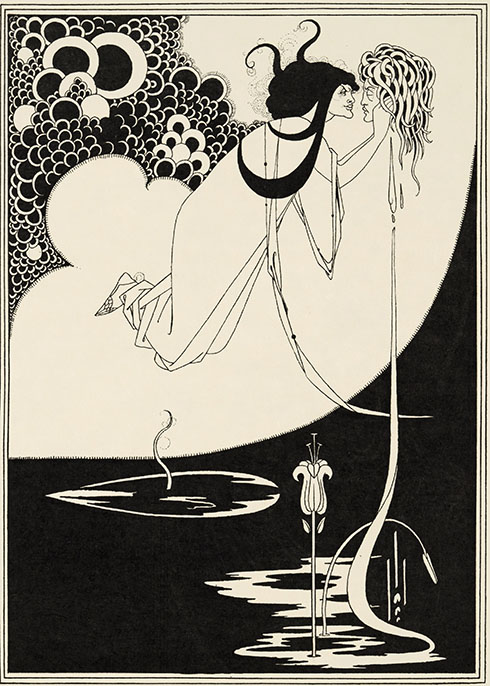

Aubrey Beardsley at Tate Britain, London, 4 March – 25 May

If much art, too, turns genteel and soft-edged as the decades and centuries pass, that can’t quite be said for Aubrey Beardsley, whose work and biography continue to feel both edgy and stylish, not least the Shunga-influenced erotic drawings – cue huge looming penises – that he asked, without success, to be destroyed upon his death. The Brighton-born aesthete, blessed with what Oscar Wilde famously called ‘a face like a silver hatchet’, was still causing London gallerists who showed his work to be pulled up on obscenity charges in 1966, some 68 years after his death from tuberculosis at the age of twenty-five; a short life, but long enough, so it’s been speculated, for him to impregnate his sister. Nineteen sixty-six was also the year of the first Beardsley revival, thanks to a celebrated show at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Tate Britain’s retrospective, the biggest display of his drawings since then, and the first in the museum since 1923, may trigger another one, fusing two eras of decadence (at least for some). Expect approximately 200 works, including the artist’s illustrations for Aristophanes’s Lysistrata (c. 411 BCE) and Wilde’s Salome (1893), plus contextual influences including Japanese scrolls and works by Edward Burne-Jones and Gustave Moreau.

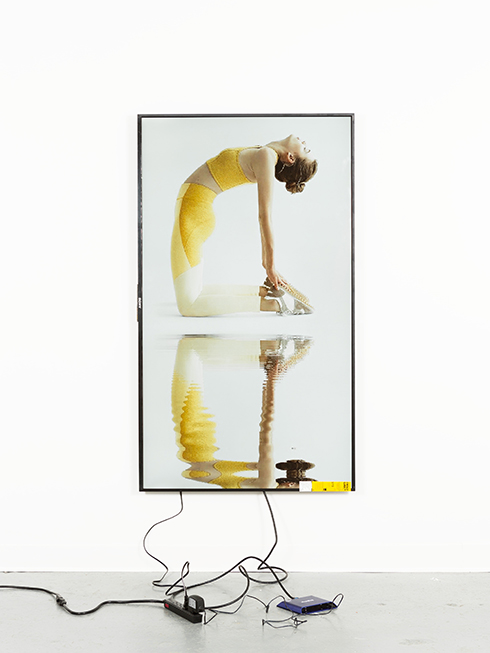

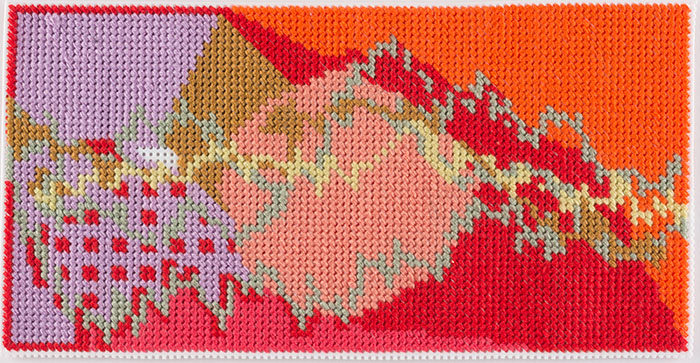

Steve Reinke at Mumok, Vienna, 6 March – 21 June

From 1989 to 1996, Steve Reinke made The Hundred Videos, an accurately titled project featuring loosely confessional, sketchlike and proposallike works, a cumulative diary done fast and cheap, that he thought would take him until 2000, but didn’t. The Canadian artist saw this as a prefatory work, a way of grounding himself as a young artist. (He was thirty-three when he finished it.) He then began another series, Final Thoughts (2007–), intended to stretch until his death; in Series Three of this, shown at the 2014 Whitney Biennial, the artist – having recently turned fifty – looked back on his life and considered which projects to carry on with, which to ditch. All of which is to say that Reinke’s life is thoroughly and reflexively entwined with his sex-and-death-related art. ‘My work wants me dead, I know. It is all it ever talks about,’ he wrote in a letter quoted on Mumok’s website, relating to his current show (and first solo museum exhibition), Butter. Alongside a new video, An Arrow Pointing to a Hole (2019), the show incorporates a series of needlepoints and a sequence of text images, ‘all of which,’ we’re advised, ‘in a paradoxically precise manner, tell of loss of control, formlessness, and self-abandon’. Sounds like a typical day’s art writing, but we’ll likely still go along.

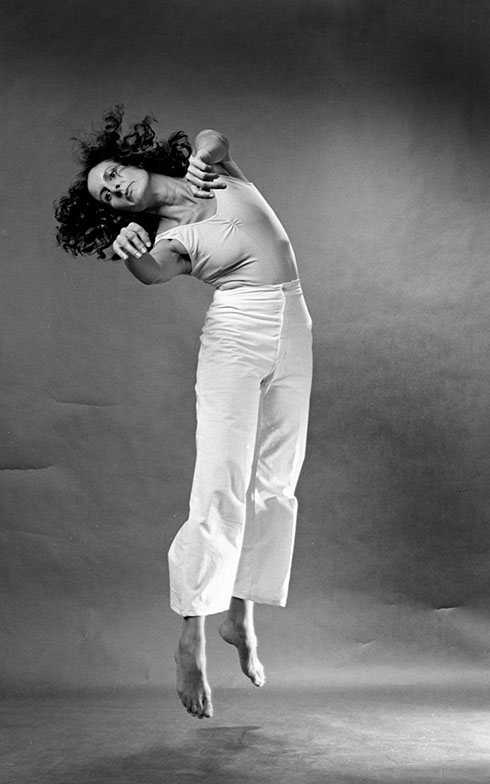

Trisha Brown at MASP, São Paulo, 20 March – 7 June

Reinke made 100 videos in a few years; over her lifetime, from the founding of her own dance company in 1970, in her mid-thirties, to her death in 2017, Trisha Brown wrote circa 100 choreographies (as well as six operas and all kinds of graphic works), and in the process rewrote dance to refract vernacular movement, mathematical sequences, abstraction and urban life. After her first decade, she transitioned from artworld settings to the traditional stage, continuing to dance herself until 2008, and snagging just about every major award in her field along the way. In São Paulo, the first major exhibition of her work, the aptly titled Choregraphing Life, reconstructs her hugely influential legacy via drawings, diagrams, photographs, films and videos.

FotoFest Biennial at various venues, Houston, 8 March – 19 April

Mark Sealy, who runs Autograph ABP, the highly regarded London-based gallery and charity supporting black photographic practices, has been tapped to direct this year’s FotoFest Biennial in Houston, the longest-running photographic/ new media festival in the us. The result, African Cosmologies, is grand in scope: examining ‘the complex relationships between contemporary life in Africa, the African diaspora, and global histories of colonialism, photography, and rights and representation’, it positions photography itself as entwined with colonialism and the Western gaze. By way of counterpoint, Sealy is avowedly leaning on the inspiration of John Coltrane, whose harmonic explorations rerouted standardised musical forms – think, most obviously, of his 1961 visionary reworkings of My Favorite Things. Thirty-one artists circle around these themes, including Samuel Fosso, Carrie Mae Weems, Faisal Abdu’Allah and Zanele Muholi. We suspect this will be rather better than the ‘tribute’ to Sun Ra that a Berlin gallery recently organised, then forgot to invite any black artists to.

Sulaïman Majali at Collective, Edinburgh, through 29 March

In 2016 a racist idiot sprayed the phrase ‘saracen go home’ on a mosque in Cumbernauld, North Lanarkshire, alongside the 4Chan slogan ‘deus vult’ (‘God wills it’). The only good thing to come out of this, aside from the heightened public awareness of hate crime via news reports, is that Glasgow-based artist Sulaïman Majali used the first phrase as a starting point and title for his show at Collective. In a monochromatic waiting room, the viewer encounters – alongside a poetic array of time-collapsing objects including a 3D print of a twelfth-century Muslim artefact from the Iberian coast, limestone and a ‘peacock sword tail feather’ – an audio collage. This, too, surfs through the centuries, from Scottish ‘orientalist’ painter David Roberts’s visit to Ottoman-era Jordan in the nineteenth century to Scots astronomer Thomas Henderson’s measurements of the distance from Earth to Alpha Centauri, taken at the Cape of Good Hope. Diasporic notions, then, are reversed, with elements of cultural exchange and scientific progress beginning in Scotland and stretching out to distant territories, suggesting the value of cultural mobility and the ignorance and hypocrisy of telling people to stay in their homelands.

Sophia Al-Maria at Julia Stoschek Collection, Düsseldorf, 8 March – 19 July

Not many artists get to invent and brand their own intellectual territory, but over the past decade Sophia Al-Maria has made ‘Gulf Futurism’ her own. The London-based Qatari-American artist, writer and filmmaker’s compound practice has unpacked this nascent aesthetic – emphatically cosigned by Bruce Sterling – with its mix of runaway urban planning driven by oil wealth and edged by climate change, conspicuous consumption and obsession with cars and tech, situating it as an avant-garde microcosm, a foretelling of where the rest of the world is heading. That said, Al-Maria is not above having her own work collected by the wealthy, and her first solo show in Germany comes under the aegis of the Julia Stoschek Collection, which has placed an emphasis on moving-image work. In bitch omega, Al-Maria offers a survey of her video- works and moving image-based installations.

Dawoud Bey at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, through 25 May

Dawoud Bey has spent some 45 years using his camera, and on occasion video camera, to record the underrepresented quiddities of black American life: from the street portraiture of Harlem, USA (1975–78), to, in the last couple of years, Night Coming Tenderly, Black (2017), a spectral series of landscapes documenting locations along the Underground Railroad, the clandestine line of routes and safehouses used by slaves to escape into free states and Canada. (Bey’s sequence of works imagines a fugitive slave’s journey to freedom.) Dawoud Bey: An American Project, featuring nearly 80 works, tracks his career through eight major undertakings, including the grimly speculative The Birmingham Project (2012), which pairs photographs of local children the age of those killed in the 1963 church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama (and the racial violence it triggered), and adults of the ages that they would be now; and Harlem Redux (2014–17), in which he returned to the streets of Harlem almost 40 years after first documenting them – and finding, of course, gentrification and displacement.

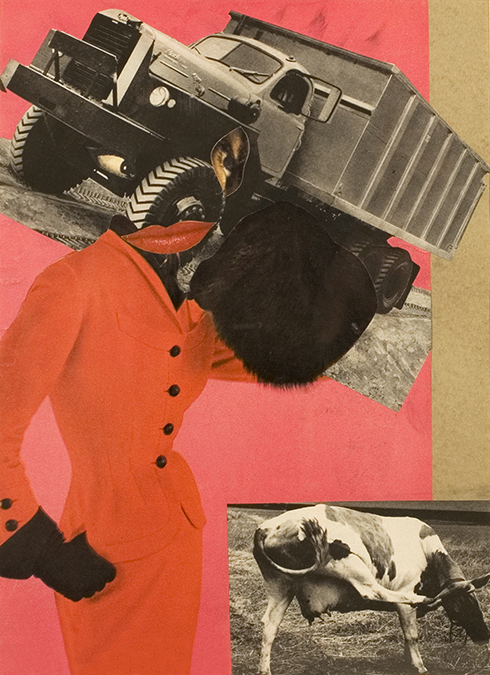

Érro at Reykjavík Art Museum, through 31 December

In 2014 Érro made a painting featuring Mad magazine’s Alfred E. Neuman, Vladimir Putin and Miley Cyrus – the latter not a bad cultural reference for an artist born in 1932, though it later turned out that the Icelandic Pop master didn’t know who Cyrus was: he’d just seen this one picture of her (with her tongue out) a lot, found her sexual aggressiveness in keeping with women he’d painted before and is generally fascinated by the technological circulation of images. The interface between tech, humanity and consumption has been a key issue for him all along, and at least some of his ideas haven’t really dated, as Cyborg ought to show. There’s a great sync between his foundational medium – collage, which he tends to use as a basis for paintings, but also on its own – and his subject matter, a cybernetic organism (as the 1960s phraseology had it) being nothing if not a collage of the organic and inorganic. Meanwhile, that Érro has tended to focus on women as his cyborg models might just align him with the Donna Haraway-reading crowd. To be fair, not all of his paintings line up with this reading – quite a bit of what he’s done playfully splices art-historical motifs with gaudy pop culture – but if this show is judiciously curated, it ought to convince.

Josh Smith at Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zürich, 13 March – 18 April

Peter Schjeldahl once described Picasso as a ‘line-drawing critter’, meaning that he wasn’t held back by intellectual self-consciousness: he just did what he did, hand hotwired to id. Josh Smith, though not on Pablo’s level, feels to act similarly. The voice in another artist’s head that might say, ‘No, it’s not ok to make innumerable paintings featuring your own name, or corny palm trees swaying against a sunset of stacked bands of colour, or dinosaurs, or overdetermined subjects like the Grim Reaper’ – he seemingly doesn’t hear it. Of course, in this respect it’d be easy to see him as a Koonsian provocateur, poking around in the unacceptable, but Smith’s painting has an effusiveness that makes it hard to take him as a tactician. Speaking of his relationship to Expressionism and Ab-Ex in an interview in 2013, Smith said, ‘I have to take everything from before when I started, simplify it, and make it something an average person, such as myself, can understand.’ You have to hand it to him: averageness is the avant-garde everyone else missed.

From the March 2020 issue of ArtReview