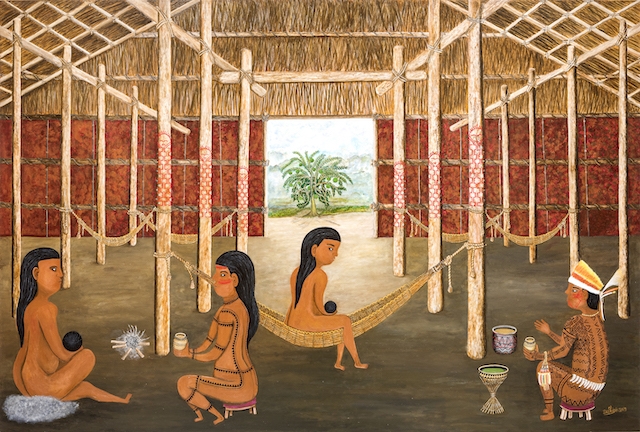

In Duhigó’s Nepũ Arquepũ, a 2019 acrylic-on-wood painting, a woman starts a month of postpartum recovery in a hammock strung across the beams of a straw-roofed, mud-floored maloca. The naked young mother cradles her newborn as the local shaman of the Tukano tribe, an indigenous people of the Northwest Amazon, sits close by, administering blessings and medicine. It is a touching, strange scene, one of many such moments in Vaivém, curator Raphael Fonseca’s densely researched cultural, political and economic history of the hammock. With exhibits ranging from arte popular to Lina Bo Bardi’s 1948 tripod chair (which features a single piece of leather strung on an iron frame), as well as contemporary works by indigenous and non-indigenous artists, colonial painting and historic documents, he uses this subject to swing round some of the most pertinent curatorial questions of our moment, not least indigeneity, cultural appropriation and the hangover of imperialism.

A series of semiabstract acrylic paintings by Yermollay Caripoune describe the Caripuna origin myth of the hammock: following the death of a baby shortly after birth, Temerõ, the creator, appears in a vision and teaches the mother how to harvest thread and weave hammock fabric, attach lanyards and anchors, decorate with a trim and suspend from a tree – a cocoon in which to keep future offspring safe, presumably. The fact that birth features in so many works here is testament to the central place the hammock occupies in indigenous life. A curatorial text alongside Isael Maxakali and Juninho Maxakali’s series of paintings depicting the process of extracting cecropia fibre, a material used in weaving, notes that the cecropia tree is known as the ‘mother tree’. In both Claudia Andujar’s photographs of Yanomami people, young and old, asleep between tree trunks, and Maureen Bisilliat’s photographs of Indigenous People in Xingu from the 1970s, naked flesh is enveloped and camouflaged by the fabric, imagining hammocks as extensions of the body.

It is a fraught journey from rainforest to urban living room, and from these idyllic beginnings the exhibition takes a darker turn. Johann Moritz Rugendas’s 1850 oil on canvas depicts a wealthy white woman in a blue dress fanning herself while being carried in a hammock by two black men. A sculpture by Aline Baiana titled Expropriation (2016) consists of a hammock loosely woven with barbed wire; an allusion, albeit unsubtle, to the occupation of indigenous lands that continues today. Denilson Baniwa burlesques questions of exoticisation in Voyeurs (2019), a digital collage in which smartphone cameras are trained on a traditionally line-drawn Amerindian family.

While the colonial powers appropriated its design for their own leisure, the hammock also became a racialised symbol of laziness. Fonseca includes plates from Mário de Andrade’s 1928 book Macunaíma, in which the titular indigenous antihero, ‘jet black’ and born to the ‘virgin jungle’, spends most of his time loafing. Elsewhere, Disney comics featuring José Carioca are displayed. The Rio-dwelling parrot, a feathered friend to Donald Duck, was funded by the Roosevelt government as part of attempts to spread US imperialism south. The bird, whose laziness is offset by his sly cleverness, is invariably shown reclining as he schemes.

Vaivém is a sprawling, comprehensive affair, and while the hammock is the central motif, it is more a MacGuffin through which Fonseca explores his hot-button themes. The exhibition could have collapsed under its own weight, yet though it took me several hours to tour, I didn’t tire once.

Vaivém (To-and-fro), Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, 27 November 2019 – 17 February 2020

From the March 2020 issue of ArtReview