Hello World. Revising a Collection at Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, 28 April – 26 August

Revisionism has coursed through art institutions for a couple of decades, as they’ve awoken, however involuntarily, to biases in their collections. This, ironically enough, has given such places a new lease of life: see Tate’s perkily hotchpotch hangs, the widespread belated recognition of other modernisms and remorse-fuelled affairs like the Hamburger Bahnhof’s audacious Hello World. Revising a Collection, which commandeers the entire venue. Here, with a roll call of 250 artists, approximately 100 works from the collection of the Nationalgalerie (collectively, Berlin’s five main art museums), 200 from other local museums and 300 artworks and documents from elsewhere, the city’s primary art establishment reimagines how, had earlier buyers been more globalist, its holdings might look. Hello World’s 13 unfolding chapters – by in-house and external curators – each underscore a transatlantic artistic conversation: Joseph Beuys’s association with Argentine eco-artist Nicolás García Uriburu, Japanese polymath Tomoyoshi Murayama’s 1920s stay in Berlin, Heinrich Vogeler’s ultimately fatal migration to the Soviet Union in the 1930s, etc. Necessarily too in this alternative history, attention is paid to how much of the Nationalgalerie collection was considered ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis and removed or destroyed.

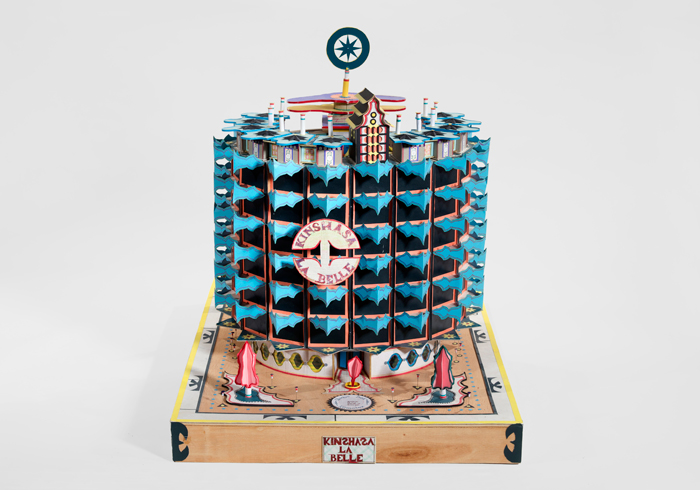

Bodys Isek Kingelez at MoMA, New York, 26 May – 1 January

Over at MoMA, institutional commitment to underrepresented voices is again visible: in City Dreams, Bodys Isek Kingelez receives his first, albeit posthumous, major US retrospective. The work of the Congolese visionary, who died in 2015, revolved primarily around fantastical models of architecture – segments of imaginary cities spiky with little buildings – and in some previous shows he’s been classed as an outsider artist. As that category leaches meaning, though, he’s now simply acknowledged as a great: ‘overseeing architect and beacon of light’, Dave Eggers once called him. The marvel of Kingelez’s world-building, outside of its abounding resourcefulness, is in visibly humdrum origins. He chivvies coloured paper, commercial packaging, soft-drink cans and bottle caps into colourful, detailed, festal cityscapes, rooted in the sprawl of his native Kinshasa but gifting it with harmoniousness. Balancing idealism and realism, his art alludes unblinkingly to issues including the AIDS crisis in Africa, postwar US/Japanese relations and the UN’s efforts in the Congo, but it is founded on optimism: ‘Thanks to my deep hope for a happy tomorrow,’ Kingelez wrote in 2003, ‘I strive to better my quality, and the better becomes the wonderful.’ A mind trick worth learning from and, here, seeing embodied.

Melanie Smith at MACBA, Barcelona, 18 May – 7 October

In 1989, in her 24th year, Melanie Smith neatly dodged the emergent Young British Artist movement by leaving for Mexico City, joining the artistic community there and using the megalopolis as source material – initially for paintings and assemblages, later for videos and films – for a twining of abstraction and socio- cultural collapse. In Spiral City (2002), which riffs on Robert Smithson’s 1970 Spiral Jetty, Smith films from a helicopter tracing widening circles over an area east of her new hometown, identikit urbanism steadily dissolving into ominous abstract patterning. Such prospective and actual entropy relating to modernity is a constant in her art, as her largest European survey to date underlines. The 35mm Xilitla (2010) tours the junglelike Mexican gardens of British aristo Edward James, dotted with fantastical concrete monuments and unfinished structures; in another nod to Smithson, workmen carrying mirrors ‘displace’ these objects, as if sending them out of time and place; Fordlandia (2014), meanwhile, was filmed in the abandoned Amazonian city founded as a rubber-producing hub by Henry Ford. Now considered Mexican enough to have represented the country at 2011’s Venice Biennale, Smith manages to frequently spiral into the past while, in terms of our collective destination, appearing ahead of the curve.

Lubaina Himid at Baltic, Gateshead, 11 May – 30 September

At Baltic, a victory lap of sorts for Lubaina Himid, fresh from securing last year’s Turner Prize; not that the Zanzibar-born, Lancashire-based artist is big on complacency. The staple concern of her paintings, expanded paintings and multimedia installations is how black history and black culture are, or aren’t, represented in art – she frequently backtracks to buried histories of British colonialism, particularly as it relates to seafaring – and here, in an area that voted overwhelmingly for Brexit, that foregrounding of marginalised narratives pointedly continues. Given the gallery’s ground floor, Himid presents an outdoor commission involving flags made from East African kanga material, which she’s used before, sometimes turning it into paintings. Kanga cloths involve patterned borders and central texts, like jazzy tweets, and are worn as wraps by women: ‘everyday wear that quite often has a funny message… they’re quite often making remarks about men,’ Himid told the writer Hettie Judah recently. In Gateshead these subversive ensigns will sync with public events each Sunday, aiming to involve under-the-radar creative communities.

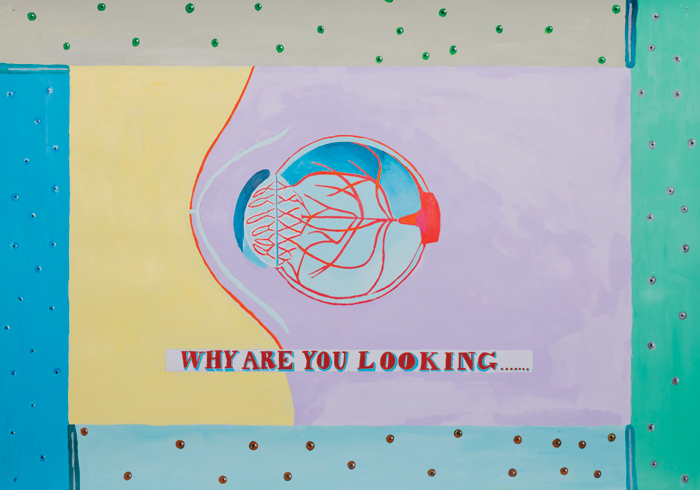

Lena Henke at Galerie Emanuel Layr, Vienna, 15 May – 23 June

Last year, in Frankfurt, Lena Henke made a work in the Schirn Kunsthalle’s rotunda that juxtaposed piles of sand with biomorphic metal sculptures that, from an elevated vantage point, resembled eyes; the prospectively painful inter-relation of those two materials, and an aggressive conception of contact, is typical of the Brooklyn-based German artist. Her recent Kunsthalle Zürich exhibition involved a spread of chain mail mechanically dragged across a set of fibreglass sculptures, their polyglot sources in turn including the work of architects and urban planners: not least Robert Moses, a figure of fascination for Henke due to his singular and deleterious effect on New York (and, by extension, New Yorkers). The kind of urbanism Henke prefers might be summarised by her proposal for the city’s High Line: a breast made of sand, steadily eroding, yielding, reshaping. If her current gallery show skews towards her smaller, biomorphic sculptures, it’s still likely to offer friction for the eye.

Jutta Koether at Museum Brandhorst, Munich, 18 May – 21 October

Since the 1980s Jutta Koether has framed painting in adversarial terms, first in heterogeneous if often bloodily red-tinted works responding to the macho self-importance of German Neo-Expressionism; then, after moving to New York during the early 1990s, progressively mixing painting and performance in a recognition that the artworld there insisted artists perform socially; and subsequently in her incorporation of materials and tropes from punk and experimental music. Nevertheless Tour de Madame is the Cologne-born Koether’s first substantial survey show. (Blame its tardiness on the artworld’s gender politics, though also a little on the artist’s longstanding dodging of classification.) The retrospective arranges more than 150 paintings in a chronological display, making sequential sense of the artist’s swerves, and traces all her phases up to a recent oblique shift into history painting. Such an overview ought to establish Koether as less an elliptical, fidgety, dark-horse presence than a cornerstone influence on recent painting, repositioning the medium as not so much the product of particular materials, rather a conceptual space to work with and against.

Karen Kilimnik at Sprüth Magers, London, through 26 May

When figurative painting hit the skids during the late 1980s and early 90s, the brilliant oddball among those who revived it (John Currin, Elizabeth Peyton, Luc Tuymans, etc) was Karen Kilimnik. She segued from theatrical environments structured like 1970s scatter art to a style of deceptively casual-looking daubing – like something from a teenager’s bedroom – that eschewed cynicism in favour of a gleam-eyed fandom for glamour, an ardency more profound than it first looked. The Philadelphian’s latest show with SprŸth Magers doubles as a micro-retrospective; she deserves a major one. We rewind first to the 1992 installation Paris is Burning (1991) / Is Paris Burning? (1944), which with its film stills, swastikas and tossed dresses establishes Kilimnik’s manner of putting times and locales into exploratory dialogue: here, the New York drag balls in the cult 1990 documentary Paris is Burning and wartime Paris itself, as glimpsed through a 1966 Hollywood movie. The show continues with paintings of fighter planes and military horses, and copies, in Kilimnik’s loose hand, of historical canvases by English and French artists. It’s yesteryear but also not; these martial pasts, like the installation’s dual references to gay, transgender and ethnic-minority revels, and to fascism, speak lucidly to our present. Expect, thusly, Kilimnik’s archival works to feel remarkably if darkly undated.

Julie Beaufils at Balice Hertling, Paris, 3 May – 6 June

The days when painting was either in or out of fashion seem far away now: painting, lately, just is. (The market helps.) In her last show at Balice Hertling, the young French painter Julie Beaufils’s canvases, all muted colour and inky curlicue, edged towards abstraction but involved scraps of imagery – recumbent bodies, painted fingernails, girlish references to Edie Sedgwick and the American TV series My So-Called Life (1994–95). Often Beaufils – a fashionista type whose Instagram gets recommended as a must-view – employed a kind of split-screen effect that made the paintings appear unresolved, like a film stuck between frames. Since then the divided frame has remained but she’s plunged into the nonrepresentational: recent paintings feature palely coloured, ambiguously scaled, rounded objects in implicit conversation. They draw and hold the eye because of Beaufils’s elegant way with a line, but beyond that they stay enigmatically mute; which, given her earlier works’ self-aware gaming with simplistic versions of femininity, may constitute a statement in itself.

Katrín Elvarsdóttir at BERG Contemporary, Reykjavík, 11 May – 3 August

Through a parallel combination of withholding and subtle accentuation, Katrín Elvarsdóttir does something that sounds simple but isn’t: she photographs the real world as if it were a cinematic narrative. In the Icelandic-born, US-trained Elvarsdóttir’s work, made all across the globe, a half-shadowed flight of steps with a slivered landscape visible through a window beside it implies a place and a before-and-after; roseate light blooming behind curtains turns metaphorical with repetition; kids walking away on a woodland path, paired with a tenebrous image of a pale hand resting against dirt, hint at hazy menace; accumulated side-on shots of caravans in mountainous territory point to unknown hardscrabble lives going on within. At least, that’s what we guess, though they could be empty. Elvarsdóttir, an adept of the psychology of looking, gets us filling them.

Bucharest Biennale, 26 May – 8 July

The Bucharest Biennale, it would have us know, is not like other biennales. They’re just emanations of the experience economy; the Bucharest Biennale, now eight editions deep, challenges all that. According to the curators, Istanbul-based Beral Madra and Bucharest native Răzvan Ion, it’s also going to expose the power structures that underwrite ‘current social, political and economic imaginaries’. Beyond that, it’s going to speak to the posttruth era, they say; it’s going to take a ‘minimalist approach’ involving one commercial gallery, one independent art centre, one artist-run space and ‘one public intervention’; it’s going to offer an eclectic tour of Bucharest while one travels between the venues; and it’s titled Edit Your Future – which syncs neatly with the fact that, at the time of writing, there’s no artist list.