The news from Hungary is pretty ominous these days, so it’s cheering to be reminded of a time when progressive art and culture flourished under an even more repressive regime. The country’s so-called neo-avant-garde – the generation of experimental artists who emerged under Communism during the 1960s and 70s – has recently been attracting attention in the artworld, where it is often regarded as a parallel to developments in Conceptual art in the West. In fact, it was a much more heterogeneous movement than the comparison implies, with space for abstract painters such as Ilona Keserü – whose work, or at least the selection displayed in her first solo exhibition in London, doesn’t align so neatly with Western art-historical narratives. Instead, the show comes across as fascinatingly multifarious, a stew of diverse ideas and influences including geometricism, hard-edge abstraction, gesturalism, even folk-art homages.

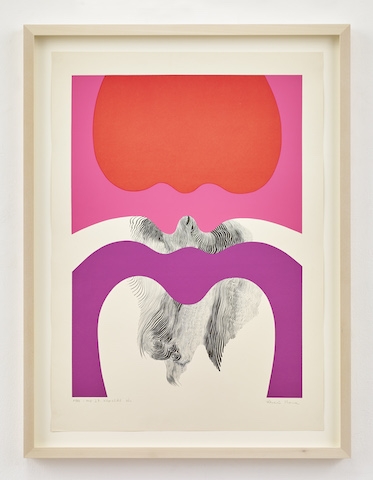

One formal element connects Keserü’s various bodies of work, though: her predilection for curving shapes, specifically the repeated motif of an undulating line, a horizontal, sinusoidal ripple. The design features in Double Form 3 (1972), for example, as a series of rolling, hilly bands of colour, created by attaching layers of slightly crimped, drapelike fabrics to the surface of the canvas. In the two-tone silkscreens, part of her June Variation and Accord series (both 1976), the wavy shape becomes more bowed and flared, repeating as stripes of contrasting colour – the overall pattern now resembling a ribcage, perhaps, or some other skeletal form, such as a tessellated stack of pelvic bones. A later silkscreen, Forming Space (1981), pushes the curves even further, extending their trajectories upwards or downwards towards the work’s top and bottom edges to create rounded, delineated areas – the resulting shapes vaguely recalling a schematic diagram of an open mouth, with the broad sweep of soft palette and tongue and the pendulous dimple of a uvula.

Such corporeal associations are inevitable, given Keserü’s palette for these works: zingy, fleshy pinks; lipsticky reds and oranges. The sense is of playfully revelling in colour, of becoming immersed in its warmth. So it’s perhaps surprising to learn that her particular curvilinear motif originally derives from a cemetery in a village called Balatonudvari, in western Hungary, where the headstones are famously heart-shaped (though apple-shaped might be nearer the mark). Keserü’s line, then, is the curvature from the headstones’ top edge, and it functions as a way of linking modernist experimentation with older folk traditions – as well, presumably, as being intended as a sort of memento mori. Beyond their surface delights, beyond the pleasure principle of their fizzing colours, these works are meant to indicate some hidden, sepulchral truth, to hint at some unnerving fusion of Eros and Thanatos.

Other series also explore ideas of corporeality or death. Four sculptural pieces from 1970 use tangles of string – more curves – as a metaphor for intestines and innards, either packed tightly into glass bottles (as in Bottle 2 (Angular)) or spilling messily down the front of a fibreboard column. The earliest work, the mixed-media collage of Television (1965), uses lace and scraps of metal to depict a TV set as something like a leering skull-face. But perhaps most intriguing of all are her paintings featuring rainbow colour effects – a smoothly blended gradient in Panneau Design 2 (1978), scribbled background flurries in All 2 (1981), patterns of hexagonal blocks in Space Taking Shape (1972) – where the bright hues are contrasted or interact with more sombre, overtly skin-coloured tones, as if making clear the distinction between the resplendent colours of art and the fleshy, impermanent matter of lived existence.

Ilona Keserü at Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, 23 March – 21 April

From the May 2018 issue of ArtReview