If you go to Sylvie Fleury’s website, you will be barraged by a storm of flashing images that flip through at the dizzying pace of subliminal messages. Glossy magazine photographs of women shooting guns or draped over cars are interspersed with her own works of art, luxury goods and advertising slogans that read ‘miniskirts are back’ or ‘yes to all’. The assault is typical of Fleury’s aggressive brand of feminism meets consumerism meets art object.

For her solo exhibition at Karma International, she has collaborated with the Parisian lipstick brand La Bouche Rouge to create four new shades of lipstick based on the bougainvillea, ubiquitous in Southern California. Along with these cosmetics, which the gallery sells for a price that straddles high-street cosmetics product and art object, are a series of purple sweatshirts inlaid with an oversize tag quoting Gloria Steinem: ‘The truth will set you free, but first it will piss you off’. Next to the clean white lipstick boxes, the neatly folded stacks of clothing look like sets of cultish uniforms. Fleury offers us the lip shades of the season, and the feminist aphorism to match.

A second ode to Steinem can be found in Gloria’s Triumph (Kawasaki 100, 1973) (all works 2018). The found motorcycle, with a custom purple paint job on the engine, plays on Steinem’s belief that, ‘inside, each of us has a purple motorcycle’. This sits in the gallery among a series of Soft Rocket sculptures that slump, Claes Oldenburg-style, against walls or on a catwalk-cum-pedestal (Catwalk). While the Steinem bike invites independence, movement and rebelliousness, the tear-shaped rockets are downtrodden and inert, phallic symbols transformed into plush pillows. Here, Fleury presents femininity as contradiction: bad-ass biker and soft, supple repose are perhaps both equally apt forms of opposing the patriarchy.

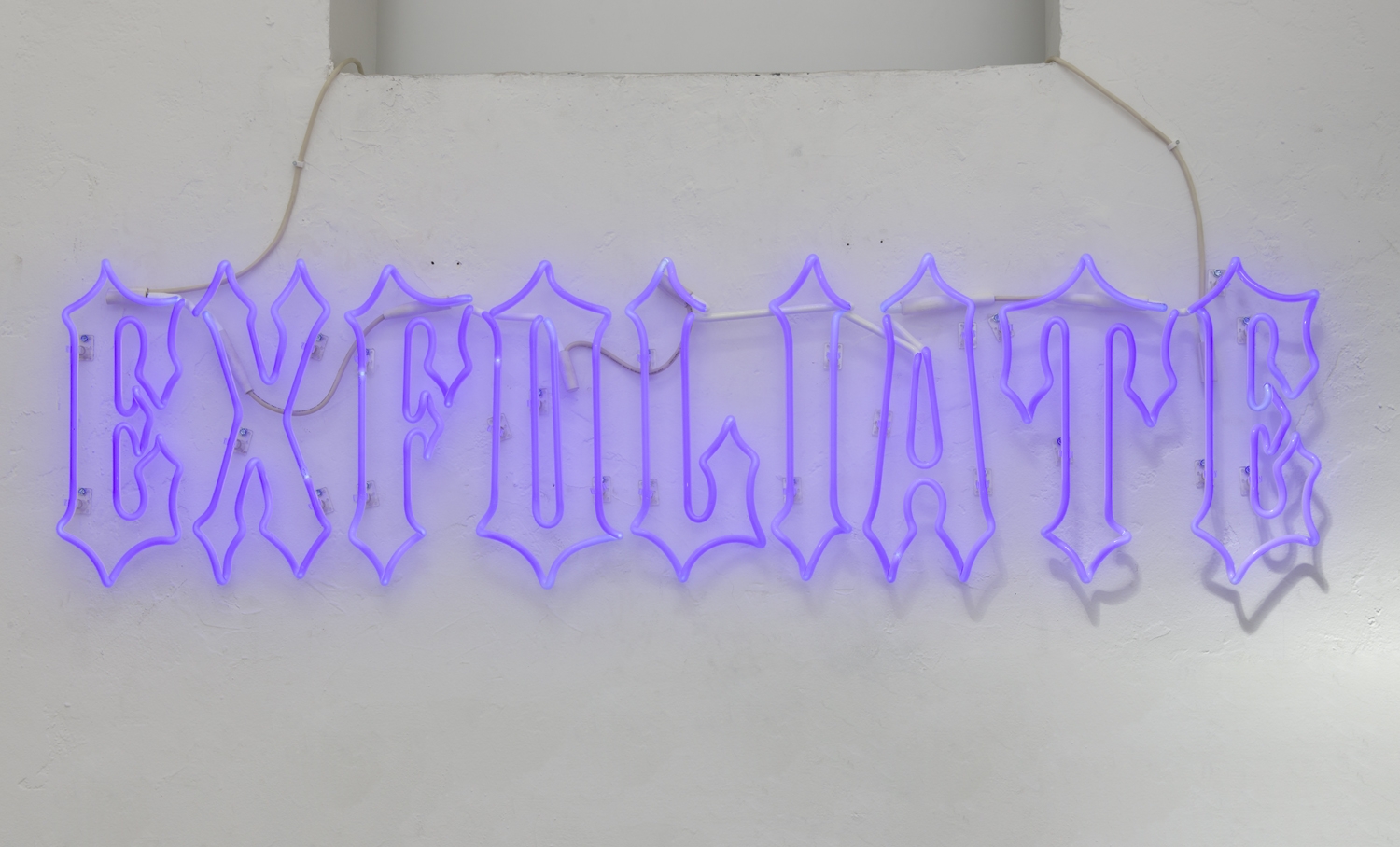

Nearby, a series of shaped canvases take their cues from eyeshadow compacts and are named after the products they resemble: Precious Rocks (Hollywood Glamour) by Dior and Envy Blush (Rebel Rose) by Estée Lauder. Fleury strips the reference down to colour and shape, inlaid into a deep matt black; these works engage with the history of Colour Field painting as much as recent fashion trends. Exfoliate, a purple neon hanging above in an AC/DC-style font, reads both as criticism and command. Take up your arms and work towards that perfect skin, ladies!

In Bad Feminist (2017), Roxane Gay describes the feminist sisterhood that ‘menaces me, quietly, reminding me of how bad a feminist I am’. Because she likes the colour pink, misogynist rap songs and orgasms, Gay imagines herself to be a disappointment to feminists of the bra-burning variety. ‘If I take issue with the unrealistic standards of beauty women are held to, I shouldn’t have a secret fondness for fashion and smooth calves, right?’ Fleury reifies Gay’s implication that the feminist and the feminine don’t have to be oppositional, but rather might be bedfellows; the compact mirror and high heel are celebrated as weapons of war. That these symbols may have been opposed by a strain of feminism that rejected symbols of a certain ideal of femininity – high heels and makeup among them – further Fleury’s output. As if through owning conventions of beauty one might find a kind of punk-rock freedom.

Sylvie Fleury: LA Bougainvillea at Karma International, Los Angeles, 20 March – 5 May

From the May 2018 issue of ArtReview