It’s 1975 and Sonia Andrade sits down for a meal of feijoada, the gloopy but delicious black bean stew ubiquitous in Brazil. In the background, over her right shoulder, a TV plays. Ron Ely is mugging to the camera in the 1960s small-screen version of Tarzan. Ignoring the show, Sonia starts to serve her lunch (it’s daytime, the Rio de Janeiro sun streams in from the balcony of her apartment). First she tucks in with a spoon but soon she discards the utensil in favour of her hands, scooping up great mounds of the dark dish and shovelling it into her mouth. She reaches for a bottle of Guaran. Antarctica and tips – no, sprays – it over her head. From thereon this scene, played out in an eight-minute video screened on a monitor similar to that in Andrade’s apartment, becomes increasingly anarchic. The artist throws the food over herself, lobs it across the room. Her behaviour, as the camera becomes the target, is wild but demeanour calm. Eventually the lens is all-but obscured by beans and the artwork ends. A brief pause. The same monitor, installed in this small but packed exhibition, flips to a second video by Andrade. It’s a shot of another television, on which Andrade is shown cleaning her teeth. She brushes gently, then more aggressively. Over the two-and-half-minute duration of this second work (also untitled, from 1977), one fears for her gums.

There are various points of departure here: formal, structuralist even, questions concerning the screen; questions of consumerism, of consumption. Both works feature the artist’s mouth: Oswald de Andrade’s oft-quoted modernist and counter-colonialist ‘Manifesto Antropófago’ (1928) is an obvious go-to (Amerindian resistance is referenced also in Lotus Lobo’s 1972 lithograph Bienal de Tóquio which features an indigenous man with bow and arrow raised). Yet the most overwhelming impression on seeing these vintage videos back-to-back is their inherent violence. Indeed, acts of aggression, of vandalism and transgression, pervade the entire ground floor of Superfície’s two-storey gallery.

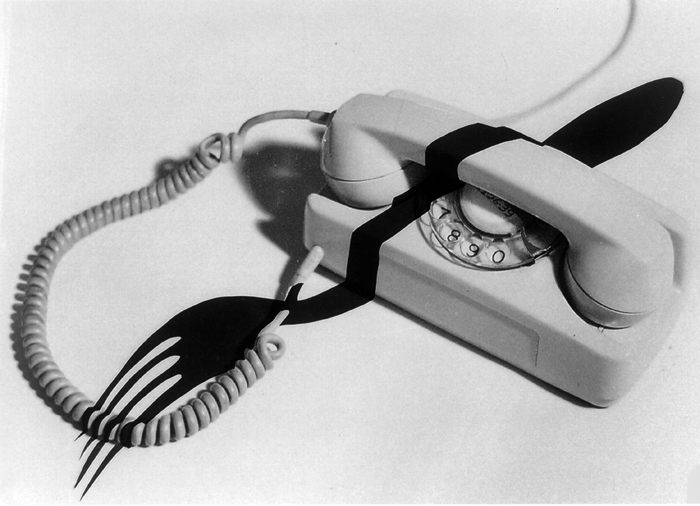

Another work by Andrade, Alimentação (Food, 1976) features a chopping board and sizeable knife; in an untitled 1974 wall sculpture by Artur Barrio the artist has garrotted a loaf of bread in half with wire. Iole de Freitas’s photographic diptych Introvert/Penetrate features a woman with a knife stuck in her neck, Regina Silveira’s photographic series Enigma (1981/1999) portrays prosaic objects (a typewriter, a handbag) spliced with the painted silhouette of a tool (a hammer, a saw). That the majority of these works were made during or soon after Brazil’s ‘years of lead’, the six years from 1968 that marked the most brutal phase of the dictatorship, is perhaps unsurprising. State-sponsored torture and execution increased and the government censorship of the press and artistic works stepped up. These are violent works made in violent times.

Filmmakers and musicians received the most attention from the security forces, while the opaque nature of Conceptualism provided a cover of safety for artists and the medium became a suitable vehicle for covert resistance. While, for example, mail art originated within the milieu of the 1960s New York Fluxus scene, largely with theoretical concerns privileging the process over the product, within the South American (and, indeed, Soviet) context it was used to congregate global solidarity networks, even if the individual works themselves were not overtly political. The upper gallery of Superfície is largely given over to various postal art projects instigated from the early 1970s onwards. Envelope On/Off (1974) features nine A5 contributions, some of which contain sly political messages. One correspondent sent in a musical sheet empty of any score, presumably a reference to censorship. A facsimile by Donato Ferrari features a portrait of the artist captioned (in Portuguese) ‘I am unpredictable’. Among the contributions to Envelope Karimbada 1 (1979) are rubber-ink stamps of three skeletons carrying a fourth. Other works on show here profess a lighter sentiment or are even touched with a certain absurd humour. From 1973 to 1984, Angelo de Aquino sent a form to peers all around the world, asking them to fill in questions concerning their identity – name, address, date of birth etc – with a box ‘reserved for your creation’. The replies ranged from American poet Dick Higgins stapling pictures of his kids and an abstract doodle by Brazilian Ivens Machado to coffee stains sent by Einar Gudmundsson from Iceland and Christo’s taping of a brown piece of paper over the document.

This exhibition might, in other circumstances, feel like an art historical curio – interesting certainly, but as academic as its plodding title suggests. However, given the show opened a week after Brazil’s administration ordered the military to commemorate the anniversary of the 1964 coup that heralded the autocratic regime, there is a renewed urgency to much of what is on show here: these old works both reflect the violence endemic in Brazil today and recall the sense of fraternity that could provide a blueprint for survival.

New Media and Conceptualism in the 1970s, Galeria Superfície, São Paulo, 2 April – 25 May 2019

From the May 2019 issue of ArtReview