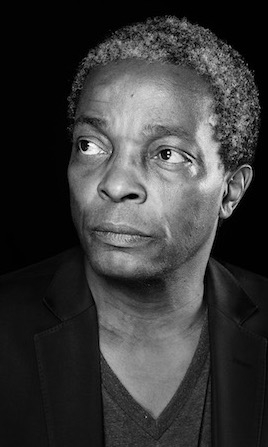

Simon Njami, writer and curator, has long advocated the development of contemporary art in and from the African continent. Curator of the influential exhibition AfricaRemix (presented in six venues internationally between 2004 and 2007), Njami has been increasingly active in Africa’s emerging biennial culture, while supporting a new generation of young curators from the continent. Here he talks to ArtReview about art, power, postcolonialism, decentring and how the first step to overcoming exclusion is to stop thinking you exist on the margins.

ArtReview How are the artistic preoccupations of artists shifting in the African scenes? Are national, traditional, regional forms changing?

Simon Njami The major shift, in my opinion, is the deconstruction of notions of Africa, identity and so on. Artists have understood that, no matter where they come from, they have to offer bodies of work that take into account the complexity of identity today. It is no longer enough to claim to be African. The definition of identity not only reflects one’s origins but includes a way of looking at the world beyond regional borders. And this, of course, is influencing the production and the perception of what it means to be an artist today.

AR What do you find most promising – in terms of content, or methodology in the artistic practices taking shape now?

SN Artists are no longer questioning the notion of identity in postcolonial terms. Instead of being busy trying to prove something to the ‘others’, they are focusing on developing a language of their own. It shows through a number of events (Lubumbashi and Kampala biennials) and initiatives (art centres in Lagos, Cairo, Cameroon) that are striving at reframing the notion of contemporaneity and contemporary art in a genuine, or should I say, more organic manner. The narratives used by the artists are a more direct reflection of what surrounds them.

AR Is artistic (self-)education and the development of critical knowledge a priority in the African scenes?

SN It is paramount. How could one develop a work of any interest without a critical gaze? Writing is key. Africa has, for too long, been talked about as a passive subject. There is today a claim to voice different ideas and different experiences and not to be any more the tool of those who call themselves ‘specialists’. A real strategy is being shaped, in order for Africans to create their own language that would contradict the dominant one, no longer as a uniform group of people, but as individuals.

AR Educating and training ‘future leaders’ has produced a number of significant curators working internationally. What are the potentials and the limits of their role in African scenes themselves?

SN We can already see the results brought by this new generation of curators and intellectuals. They have understood the importance of ‘working at home’. Because no matter the success they might encounter abroad, they need to fuel their reflection with what is happening on the continent. The limits, for some of them, will be to mistake the real ‘game’ and think that whatever power they have achieved is coming from outside. Those who are going to bring major changes need a certain level of legitimacy that can only be acquired by a greater knowledge of what is at stake in order to become the spokespeople of the new generations.

AR How might large exhibition events like biennials be a form of soft power in the African scenes?

SN Large exhibitions tend to function as loudspeakers. They address an audience that is both inside and outside of the national territories. And in doing so, they introduce a certain togetherness that breaks the boundaries of national identities. They also play the role of laboratories for things to come. Last but not least, they create a sense of pride. Most of the important exhibitions about African art were thought, conceived and shown outside of the continent. I remember the emotion provoked by the opening of AfricaRemix in Johannesburg: most of the local newspapers wrote, ‘AfricaRemix comes home’. There is a strong psychological dimension in what big events might produce. Not only to the ‘usual suspects’, but on a political level as well. It creates a sense of belonging that is priceless.

AR What are the prospects for the development of art’s commercial power in the region? Is the growth of the middle class a necessary factor?

SN All the sociologists agree that middle classes are what shape a country. I think that in the case of Africa, it goes both with education and hype. I have witnessed the tremendous changes in the Angolese and Nigerian scenes. People are becoming more and more aware of the importance of culture in the making of a nation. And in this struggle, everyone has a role to play. When we opened the first African art fair in Johannesburg some years ago, my message to the audience was quite clear: you may rightfully complain about all the treasures that were stolen from the continent, a situation that made it difficult for Africans to have a privileged relationship with their own productions. It also created a huge gap in the theories and practices. Today you have the opportunity to write a new page of history. Don’t complain if, tomorrow, all the major productions of the time are hosted by Western museums and collectors.

AR You mention nation-making – do you see artists, critics and curators relating themselves to nationality and locality, at a time when the artworld is becoming more networked and (for some, at least) more mobile?

SN The way I use the term ‘national’ does not refer to borders. On the contrary. After the Berlin Conference of 1884–85, the African continent was divided in an artificial manner. What I mean is that, in order to talk about Africa, we should be able today to address the countries that are composing this ensemble. The stories are never totally similar. They are languages, for instance, that shape territories regardless of the political divides. In order to create that mobility you mention, one needs to know the nature of what is being moved.

AR Do governments and politicians have a new interest in the forms of presentation contemporary art offers?

SN Some of them do, but they understand the diplomacy power of culture. Few understand its economic interest. Some others are still suspicious about the meaning of contemporary productions. They are still living under the Western influence. Ironically, most of the artists who were recognised at home only made it because the West has praised their talent.

AR Where do you see power moving to in the global artworld – not simply in terms of commerce, but in terms of cultural power, or in emerging forms of institution and presentation?

SN The global artworld needs to redefine itself. We have witnessed the changes introduced by the arrival of the Middle Eastern players. Some other regions might enter the game: India, China… The market that we know is going to open to new players with different criteria, gazes and strategies. I think this shift should work to the advantage of non-Western countries that are not formatted yet by the ancient market. But in order to benefit from this redistribution to come, they need to be ready. The young generation of curators or cultural activists I have mentioned have been creating tools (exhibition spaces, workshops, seminars) in order to increase the level of awareness on the continent. It is always interesting to witness the shift between a project conceived and performed locally and a project conceived abroad and ‘imported’ into the continent. One has to deal with the local realities (funding, audiences, communication…). It forces the young generation to create new models and new ways that they wouldn’t necessarily think of outside of a given context.

AR In many art centres around the world, political freedom and democracy is often constrained. Can the artworld – as it is evolving in Africa – have a role in influencing positive change in that respect?

SN The advantage of art, in many countries, is that it is still perceived as a minor form of expression. The politicians focus more on the written culture, which they find more explicit, and hence more dangerous, for them. Art can bring a subtle contradiction, instil a soft rebellion that may be perceived by people and not by the leader. In Senegal, for instance, the Y’enamarre [‘We’re fed up’] movement was initiated by artists when the former president tried to change the constitution. This group of artists found a tremendous echo in the population, and the presidential project was abandoned. Everyone knows that an artist is never seeking a power position. It allows people to trust them more than any other social actor, because they have ‘nothing to win’ in the battles that they are fighting.

AR Does the West matter so much now? And is China just another problem?

SN The West still functions as a distorting mirror. But in reality, it does not hold the power it used to have any more. People have been starting to move differently through the world; the old ‘centres’ are not what they used to be. As for China, it is too early to predict. They are too busy trading and making money. But, logically, sooner or later they will enter the game. The non-Western countries should be able to play with the different scenes that are opening. They are no longer condemned to go through the same routes.

AR What might internationalism be today?

SN I don’t really know. I am not even sure I like that term. I would rather go for universalism, but the way Aimé Césaire described it: the sum of all particularities. It sounds like a wishful dream, for the time being, since all the major decisions are taken by a small number of people. Of course, the situation has improved over the years. Yet it is up to the ‘excluded’ to build strategies for having their say in the global scene. The general feeling, for those who are not part of the global players, is that of exclusion. But that attitude is very negative. In the same way that Derrida said he has no sympathy for the victims, I could say that I have no sympathy for the excluded. Because in order to feel excluded, one has to decide on what is the centre and what is the periphery. For too long a time, the centre has been perceived as being in the West. The first change is hence mental and personal: to change from being the object of external decisions to assuming different possible centralities.

From the November 2018 issue of ArtReview