A friend once described sex with a violinist as being “like music”. I understood what she was trying to say – it had been harmonious, their bodies in sync – and I congratulated her on getting laid. But the comparison irked me. It reminded me of the misuse of ‘poetic’ in earnest exhibition reviews or the ‘artistic’ that crops up when critics get flummoxed by that film director who uses languid closeups of Spanish moss or a janitor washing his hands. Music can be awful, filled with terror and unspeakable pain, I thought. Had their intercourse evoked Schubert, or something equally tender, as my friend’s doe eyes implied? Or was it closer to Schoenberg, Skrillex, the Spice Girls?

Music is under no obligation to be enjoyable. It’s pleasant when it is, but it’s often most affecting when it’s not. ‘You can’t always write a chord ugly enough to say what you want to say,’ Frank Zappa remarked, ‘so sometimes you have to rely on a giraffe filled with whipped cream.’ Here was a composer who understood the limits not only of euphony but of what so often passes for seriousness: sometimes you need a Trojan ungulate stuffed with aerated absurdity to communicate a feeling that would elude more conventional forms of expression. Sometimes you need to scream.

‘You can’t always write a chord ugly enough to say what you want to say,’ Frank Zappa remarked, ‘so sometimes you have to rely on a giraffe filled with whipped cream’

Creamy giraffes and their sonic counterparts were on my mind when sitting on the bum-numbing steps of the ICA’s sunken first-floor gallery in August. Sound and light were spilling into the notoriously leaky space through the dusky entrance-hall-slash-bookshop and wafting all the way to the bar at the hall’s far end, where patrons, starkly outlined against the white walls, nibbled deepfried arancini and suckled pints of Asahi. The audience settled in rows of chairs in front of me, facing a projection screen.

I was here to see Elaine Mitchener’s free-jazz trio The Rolling Calf perform live soundtracks to a series of films by, or about, their predecessors in the black avant-garde: Albert Ayler, Sun Ra, Donald Rodney. The three musicians stood on the floor to the right of the audience, surrounded by wires and effects pedals. A projector whirred to life behind me and threw onto the screen the image of a lifesize cutout of a woman afloat in shallow waves or propped in dense forest. She looked lost, fragile, frozen. I grew tense and afraid. And later, sure enough, she was set alight, curling up to flame and smoke.

The Rolling Calf channelled the film’s menace and alienation through sheets of dissonance. Mitchener’s mouth-clicks, howls and flickery whispers were accompanied by washes of noise from the bowed double bass and piercing screeches from the saxophone. A frenzied recording of a Sun Ra concert filled the screen. The music was relentlessly abrasive. I caught myself hoping the film would end soon, then chided myself: pay attention. It felt vital that I subject my ears to flagellation by something approaching pure noise. Yes, I could instead have wandered into a building site. But I wanted a dose of free jazz, a genre I’ve often dismissed as a po-faced musical tantrum for chin-stroking, latter-day beatniks, the unbridled discordance of which, in Mitchener’s hands, served an altogether more powerful purpose. By invoking a form that, when it emerged during the mid-1950s from the black avant-garde, amplified the anguish and hope of the civil rights movement, the trio brought a question to bear on the present: how much has changed? And if the answer is ‘not nearly enough’, how might you even begin to express the scale of that injustice without making a tremendous racket?

I glanced at the bar. The contrast between the adjacent spaces was comically stark. Bright politeness in one, shadowy howls in the other. The bar was a different world, but sounds were trafficking across the divide. I wondered, with more self-righteousness than I’d like to admit, how annoying it must have been for the patrons to raise their voices against the gut-wrenching din from next door – music that spoke of pain and rage when all they wanted was a glass of house red. I began to feel that I was sitting in a metaphor for how easy it can be to live with, or ignore, the horror and discord of history – or the tumult and dread of the present.

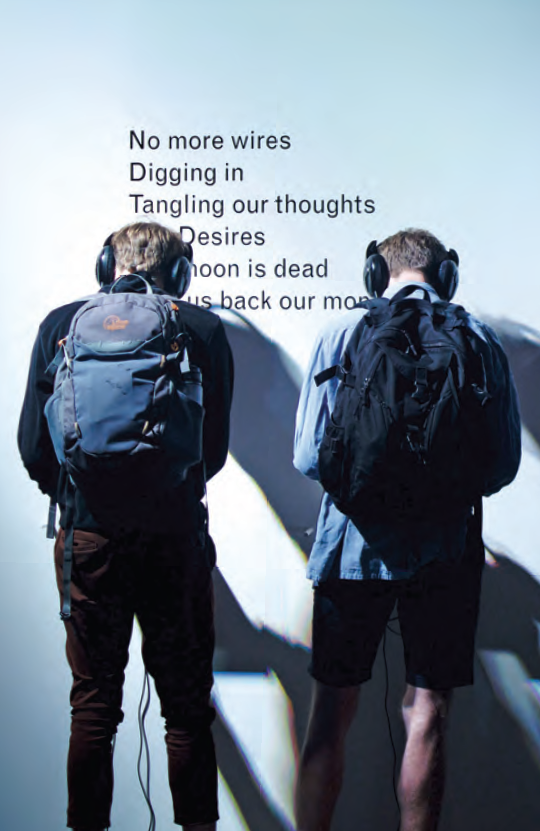

A disconcerting comparison came to mind. In his experiments at Yale, Stanley Milgram used an ugly sound – specifically, the sound of a person screaming behind a partition – to measure the extent of our ability to inflict pain on others when told to do so. Most people, Milgram discovered, ignored the screams and kept hitting the button they were told would administer shocks to the unseen person. I wondered to what extent people who look to culture for catharsis, myself included, could be accused of a similar negligence: of hearing screams leaking through the partitions of race or class but finding it easier to sit in darkened rooms for determined periods, electively punishing our ears, than pay proper attention to those more troubling sounds. The final film ended: free jazz relaxed into applause. I returned to the dusk, the trio’s music echoing in my ears and mixing with traffic in the darkening city. Almost without thinking, I put my headphones on, opened Spotify on my phone and selected a song I knew would lift my dark mood as I walked to the station.