Marinaro Gallery, New York, 3 May – 18 June

Plonking a title as generic as Travel Pictures on this group of wonderfully surreal, oddball paintings is a savvy move by Ridley Howard: you expect anodyne, decorative scenes from some grand tour; you get an artist showing off his formal chops. These paintings, some of which are ostensibly set in Italy, put me in mind of the photographs of the late Italian Luigi Ghirri: peripatetic snapshots, colourful dispatches from some land of the weird.

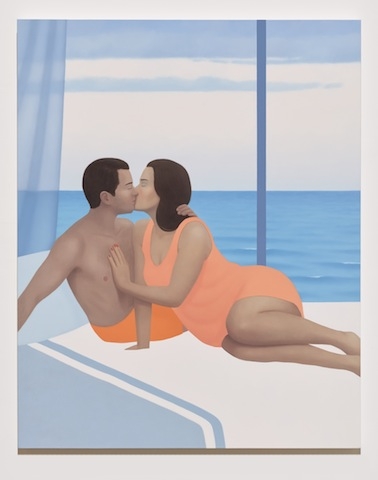

Howard has long experimented with complementary modes of working. Abstract and figurative strains have occasionally entwined, or at least tickled each other. Around 2012 he was showing them side by side: soft-focus portraits juxtaposed with gentle, geometric workouts. A year later, and continuing with Travel Pictures, the artist fully collapses these modes into single compositions, the simple-but-revolutionary strategy that seemed to be sitting there all along – a way simultaneously to paint architecture, sex, shapes, the patterns on a dress, cruise ships ploughing through cool blue rectangles of ocean.

Here, the viewer is basically a tourist in the uncanny valley. The archetypal Howard protagonist has always had something airbrushed about him or her, a blank facial smoothness that I can’t help but associate, horrifyingly, with Jared Kushner. In these latest paintings, the artist seems even less concerned with verisimilitude: vaguely cyborgian humans cavort in literally dreamy settings. (In Miami Beach View [all works 2017], a woman’s hand simply dematerialises where it touches her bedsheets: a glitch in the system.)

Howard has previously spoken about his affinity for 1970s European movie-poster design – for films by Jean-Luc Godard, Michelangelo Antonioni, et al – and Travel Pictures is often operating in a distinctly Felliniesque groove. What would otherwise be polite, even fusty, landscapes are punctured by illogical cameos. The effect is a bit like what you might find in a travel agency advertising vacations in the afterlife. In Passeggiata, Rome, the curve of a tree-lined road is jarred by a pair of legs, sporting high-heeled shoes, that hang suspended in midair. Kissers in the Mountains sneaks two paintings into one: a fuzzed-out mountain on the bottom and, up top, two disembodied sets of heads making out against a pale yellow background. (The two images are separated by a border of grey, white and pink lines, a little Neapolitan moment.) In Benvenuti Lovers (the painting here that is closest cousin to Ghirri’s photographs), two women pose in front of what is either a picturesque, boat-filled harbour, or merely a picture of a picturesque, boat-filled harbour.

Howard has always had a delicate touch and an eye for the drama of small gestures. That’s evident in this exhibition, perhaps nowhere so much as in its smallest painting: Winter Painting, a shoulders-up portrait of a young man in hip glasses. A kind of arctic paleness prevails – white walls, white T-shirt – but the eye is drawn to a single red line, like an unfurled Kabbalah bracelet, which is either embossed on the man’s shirt or, perhaps more likely, floating in space before him. Lazy journalists are fond of asking artists that hoary question: how do you know when a work is finished? I can imagine Howard struggling with this portrait, mulling it over, and then – with that thin, graceful mark – putting it happily to rest.

First published in the September 2017 issue of ArtReview