Hauser & Wirth, London, 19 May – 29 July 2017

In 1971 Philip Guston returned to the us from Italy, having spent half a year getting over the negative response to his latest show of paintings. His apparent rejection of abstraction in favour of a strange new figurative direction had elicited bafflement and anger from his New York peers and most critics, and Guston at this point could easily have been forgiven for reverting to his previous style. Instead, upon his return he produced, in just a few frenetic months, hundreds of deliriously satirical drawings on the subject of President Richard Nixon, caricaturing him as a depressive, manipulative schemer, a bollock-cheeked, schlong-nosed grotesque who was out, indeed, to screw the world over – pretty prescient, given that the damning scandals of Watergate were still some way off.

As well as acting as a channel for Guston’s political ire, then, the ‘Poor Richard’ series (as he titled his personal selection of 73 of these drawings) can be seen as a statement of intent, an affirmation of his commitment to the clunky style and peculiar motifs he was developing. It’s fascinating to witness, for example, how the Klansmen imagery, which had debuted in that controversial painting show the previous year, is brought in, with Nixon at points depicted as a sort of ghoulish, empty cowl. Indeed, if anything, Guston was accentuating the very tendencies that had produced such a mystified response to his new work. The paintings had been stigmatised as crude and cartoonish? Then he would produce actual, out-and-out cartoons. He was being accused of abandoning abstraction, of retreating from its purist prohibitions against subject matter? Well, how about possibly the grandest subject matter of all, the topical events of national politics?

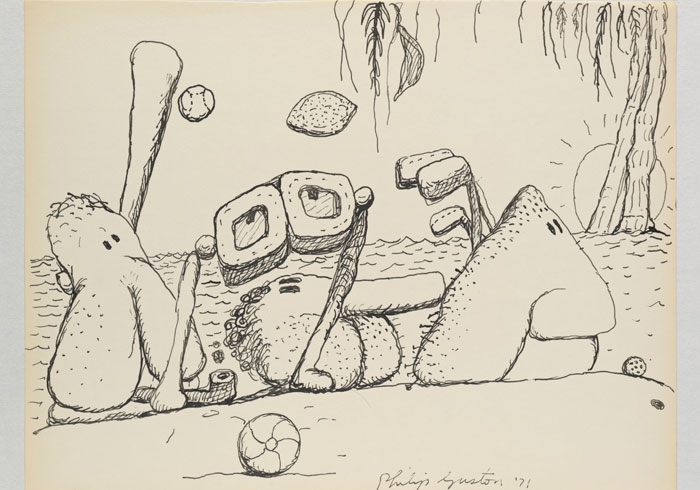

Not that all the events Guston portrayed had literally taken place. About a quarter of the current exhibition – the original ‘Poor Richard’ drawings plus scores more discovered posthumously – covers Nixon’s famous trip to China. But in 1971, the China trip, which Nixon intended as his political legacy, was still at the planning stage: so the images of Nixon shovelling his penis-nose into bowls of rice or dressed up like Fu Manchu were pure, scabrous speculation. Nor do the works focus exclusively on Nixon: Spiro Agnew, the vice president, and Henry Kissinger, secretary of state, also feature – the former portrayed as a lumpen, triangular head, the latter identified simply as a pair of freefloating, sinister-looking spectacles. The political triumvirate together forms a sort of demented, pathetic posse, rife with power struggles and codependency issues – whether mooching around the beaches of Nixon’s so-called Winter White House in Key Biscayne or squabbling among themselves at the golf course.

In that sense, the works are clearly informed by George Herriman’s surreal, magisterial Krazy Kat cartoon strip (1913–44), which Guston read avidly as a child, and which featured a similarly tangled trio of characters. Herriman’s influence on Guston’s late work is well known; but the fact that these are drawings means it’s far easier than it is in Guston’s paintings to trace direct borrowings: the black, saucer-ish eyes; or a brick being thrown, clearly a homage to one of Herriman’s recurring gags. Above all, what Guston inherited was a certain tone: figures mordantly playing out their assigned roles in a sort of theatrical, symbolic space.

That tendency is pushed furthest in a smaller series of later Nixon drawings – the ‘Phlebitis’ series (1975). Yes, Nixon had problems with an occasionally swollen left leg. But in Guston’s savage depictions his limb becomes monstrous, an elephantine mass of veinengorged, suppurating flesh – a portrait not just of the president but of the post-Watergate us as a whole, utterly maimed and dragged down by corruption.

From the September 2017 issue of ArtReview