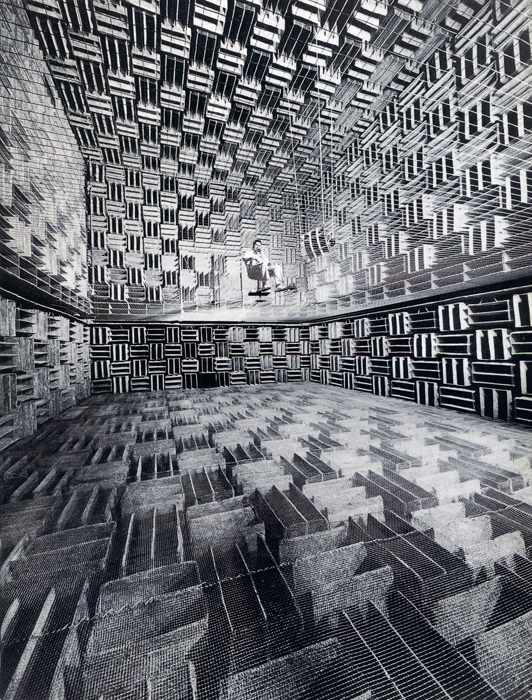

I recently treated myself to a pair of noise-cancelling headphones. I should have done it years ago. They have improved my life immensely. As one irate Amazon reviewer pointed out, in a fit of buyer’s remorse, the headphones don’t quite cancel noise, not entirely. That would be impossible. After visiting an anechoic chamber at Harvard in 1951, John Cage observed that, once external sounds had been removed, he could hear the low hum of his blood and the high whine of his nervous system. (The latter is controversial: it may have simply been tinnitus.) ‘There is no such thing as silence,’ he concluded of his revelatory encounter with quiet. It hasn’t stopped scientists attempting to engineer it.

As the irate reviewer notes, my headphones don’t cancel. They dampen, mitigate, soothe. This act of sonic subtraction, which has done wonders for my ability to focus on work or zone out during long commutes along grinding train tracks, is revealing in itself. The ambient disarray of our acoustic commons subsides at the click of a button. In its absence, I hear, perhaps paradoxically, the sound of noise-cancellation at work – a process in which unwanted sounds are more or less erased by soundwaves of equal amplitude but inverse phase. (A process of addition, then, rather than subtraction: of sound destroying sound.) The result is a high-frequency residue of normal hearing that, to my ears, has an unmistakably dry quality. It makes me think of iced Campari, a bitter, crisp drink for the ears.

I’ve recently become preoccupied with sound and how it influences – saturates – my experience of basically everything. It’s partly a belated effect of growing up with a pianist grandmother, sitting at her side while she taught me Chopsticks, observing her hands as they crossed the keys, and understanding that the soft hinged clack of the action being pressed was as satisfying to hear as the notes they summoned. And it’s partly a result of living in 2019, when spending two seconds on social media, tuning in live to the latest Westminster meltdown or hearing language itself further debased with every fresh wash of the news cycle fills me with a desire for noise-cancellation on a global scale.

I’m working on this piece at the library, or trying to, when a school group in matching hi-vis tabards bursts into a full-throated, borderline atonal rendition of Baa-Baa Black Sheep in the picture-book section behind me. (Sorry, kids: the sheep drowned in a flood, you will inherit a ruined earth.) I flick the switch – ah, that crisp hiss – and my head is suspended in a private, sound-proofed booth, a black box for the mind. The kids are still there, but it’s hard not to feel affection for their exuberant, Johnny Rotten-ish howls, now that the edge has been taken off.

Becoming aware of a reduction in noise makes me more aware of what I’m missing – the remainder that refuses to be erased. This, I realise now, is what makes sound so exciting for me, and such a headache for curators: its spooky refusal to stay in the frame. It’s always going places it shouldn’t, leaking, seeping, infiltrating, however hard we attempt to suppress it. It careens around corners, leaks from monitors, wobbles through walls. The German word for sound art – a loose, slippery term for a bunch of practices that blur the distinctions between music and art, concert hall and gallery – is predictably evocative here: Klangkunst. The word itself reverberates. Sound clangs in ways we don’t always expect.

I was reminded of all this the other day, while standing in the genteel confines of a Mayfair gallery, frowning at the fleshy smudges and crimson smears of an abstract painting. A car with a thumping sound system drove past. Its subwoofer was so loud I would have needed a Richter scale to measure it. The gallery was physically affected by sound, perhaps even structurally compromised. Windows hummed in their frames. Pictures buzzed on their hooks. These noises blended with the drone of the aircon unit above the entrance, the clack of desktop keyboards behind the front desk, the hum of fluorescent tubes, the sigh of traffic muffled by glass, the squeak of Nikes on polished concrete, the invigilator clearing his throat, all of it overlapping, interfering, blending, causing me to project a state of momentary confusion onto the painting itself. The car drove past. A monkish hush resumed.

Which was the more conducive state, I wondered, to appreciating that (or any) painting? I don’t think of the car and its weapons-grade sound system as having intruded on my pure, solitudinous contemplation of a visual object, because such purity, like silence, simply doesn’t exist. Sound is integral to the experience of art. You can’t cancel the noise, just reduce it. Listening conditions looking, and vice versa. Perhaps the two are inextricable. Here’s a quick test: are you looking at this sentence, or hearing it in your inner ear?

Patrick Langley is the author of the novel Arkady (2018) and an editor at art-agenda

From the September 2019 issue of ArtReview