From 2017: The artist confronts politics, danger and self-invention in her portraits of lesbian and trans South Africans

‘Zanele the fire-eater’ is how one of her most ardent sitters describes her. For a decade and a half the South African photographer Zanele Muholi has been an indomitable defender of LGBTQ rights in her native country, where those rights (though extensively codified under South African law) are under constant assault. Muholi was born in Durban in 1972, and worked in factories and then as a hair stylist before taking up photography, initially as a purely documentary practice. In 2002 she cofounded the Forum for the Empowerment of Women: an organisation that gives support and shelter to black lesbians. Muholi at this point began documenting antigay hate crimes and in particular the ‘corrective’ rapes perpetrated against lesbians. Around the same time, she studied photography at the Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg (she already knew the photographs of its founder, David Goldblatt) and began making a body of work that includes intimate studies of queer life in her country – such as the photographs of naked and embracing couples that make up her series Being (2007) – and latterly some furiously playful self-portraits.

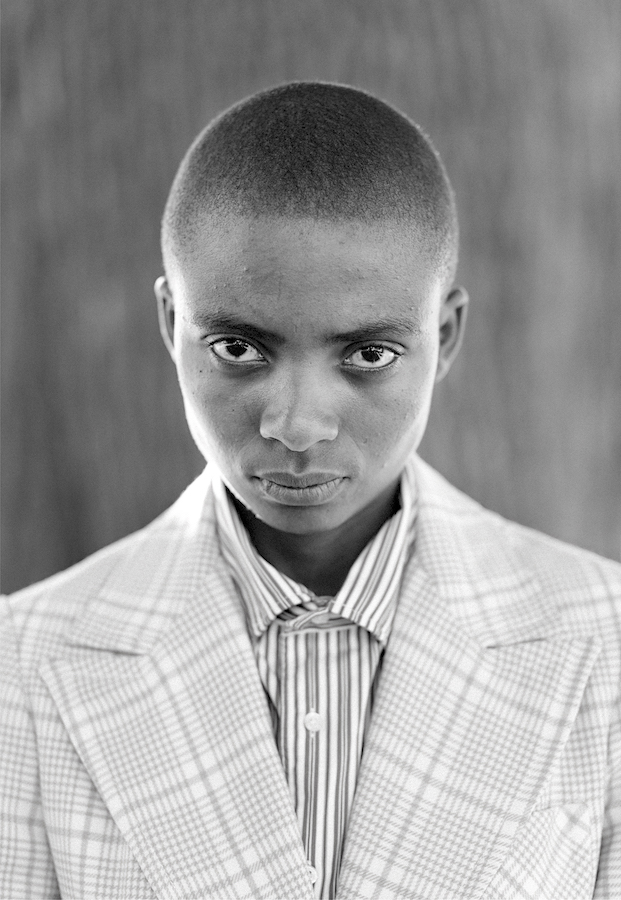

Muholi’s largest undertaking to date has been Faces and Phases, an ongoing series – ‘a lifetime project’, she says – of black-and-white photographs of South African lesbians and trans men. There are 258 such pictures in the eponymous book she published in 2014, from the first eight years of the project. They are mostly three-quarter-length or head-and-shoulders shots, and it seems that all of her ‘participants’ (as Muholi prefers to call them) have dressed up to address the camera. Striped shirts and popped collars abound, neckties and bowties and neat waistcoats; here and there examples of the globally popular hip-hop-golfwear nexus.In part, Faces and Phases is an archive of close to a decade’s worth of sharp, queer dandyism – an affront, via the persistence and the collectivity of style, to a culture that still disparages gay life and culture as mere fashion.

Consider Makho Ntuli, aged forty-three when Muholi photographed her in 2010. She’s been married, had three children, left her cheating husband and pursued relationships with women, ‘because that was what I had been suppressing in our time together’. Muholi frames her against a nondescript black background, head shaved and shirt buttoned up to her neck, the pointed collar of her white jacket setting off her equally sharp expression, as though she’s arrived at some ideal of purpose and precision. Or young Palesa Monakale, photographed in Cape Town in 2011, with her waistcoat and low-slung belt and chunky retro headphones and digital watch – also an eyebrow dramatically raised as if to say she knows exactly what such style still costs (emotionally, physically, politically) in South Africa.

In part, Faces and Phases is an archive of close to a decade’s worth of sharp, queer dandyism – an affront, via the persistence and the collectivity of style, to a culture that still disparages gay life and culture as mere fashion

Some of these portraits have accompanying texts: poems, autobiographical essays, in a few cases extracts from newspaper articles about the person photographed. Many or most of these recount familiar stories of the participants’ coming-out: confiding in teachers or family friends, being rejected or embraced by parents and siblings, finding a community among the groups where Muholi has been a high-profile organiser and ‘visual activist’. (The distinction between artist and visual activist, which may seem moot, seems for Muholi to come down to the way she thinks about her participants as part of a collective, of which she is archivist and witness.) What sets these accounts apart, though, is the regularity with which stories of corrective rape emerge. Here is Pamella Dlungwana (whom I quoted at the start) with her bleached crop and her angry stare: ‘The morning after I was raped I woke up to write my matric biology exam… I took it like a man, wrote the rest of my exams, did not press charges.’ Predictably, many of the rape survivors are HIV positive. (‘I have two birthdays,’ says Nunu Sigasa: ‘I was born on 10 October and I was diagnosed HIV positive in February, so each and every 15 February my HIV status turns a year older and I get to live another year.’) In Muholi’s photographs, they’ve put on a certain armour against the corroding anxieties of their lives, using hair, clothes and their address to the camera to invent personas that are variously butch, hip, extravagant or precariously conventional.

The people in Faces and Phases make frequent reference to the real and metaphorical shelter they’ve found among activists like Muholi. Portraiture itself is a sort of refuge or protection, as well as a potentially lethal form of exposure. Time and again the participants comment on the importance of being part of Muholi’s project – the photographs propose a community among women isolated by geography, class and the need for secrecy – and the very real danger that when these pictures are seen their neighbours will want to kill them. As Dlungwana puts it: ‘she’s shot enough wailing and keening to wake God from his slumber and made all phobes aware that we’re here like mice, rice and lice.’ Their faces seem to express pride and reserve at the same time: almost everyone looks straight at the camera, with expressions varying from the sombre to the slightly quizzical. And among these faces is the artist-activist herself, in big 1970s glasses and leopard-print shorts against leopard-print backdrop. Or cutting an aristocratic figure in her blazer and her floral shirt – there is something curiously antique, almost Victorian, about Muholi’s self-presentation, or self-invention, in the middle of her own series.

The historical reference is not accidental; Muholi’s work is complexly oriented towards the long history of colonial photography of black faces and bodies, as well as the efforts of black artists and intellectuals to project counter-images. In particular, she links Faces and Phases to the 363 images of African Americans that the scholar and civil-rights activist W.E.B. Dubois assembled in 1900 for the Paris Exposition. When Muholi first saw those images, she recalled (in a 2011 interview with poet and critic Gabeba Baderoon), ‘I just wanted to cry. What I’m doing is what has already happened. There is a line of black women in photographs taken back to the nineteenth century.’ Faces and Phases is ghosted too by the portraits taken for the South African apartheid state’s notorious pass books, the identification black South Africans were required to carry if venturing outside their designated, segregated areas, and by the work of the photographer Ernest Cole, the country’s first black freelancer, whose 1967 book House of Bondage includes pictures of black South Africans being arrested for infractions of the pass-book laws.

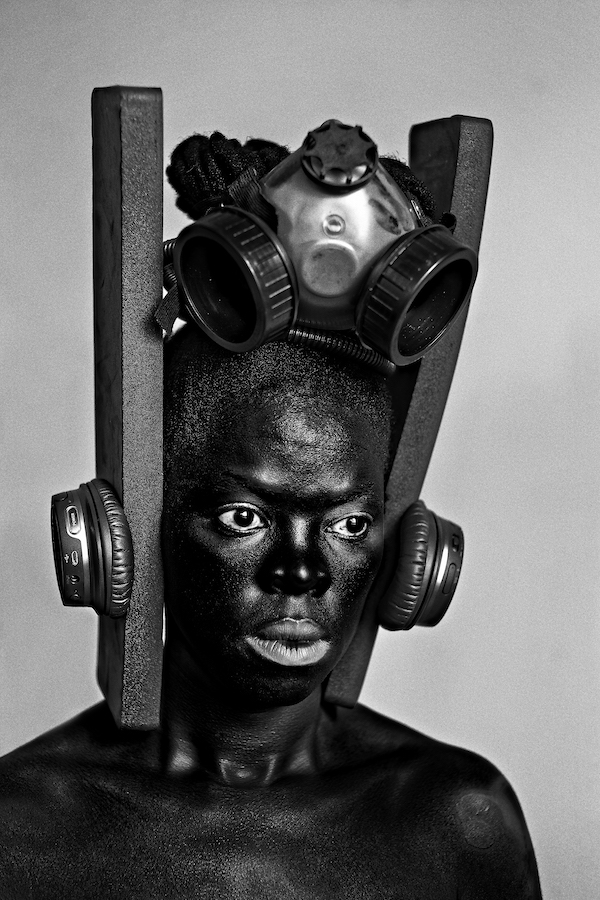

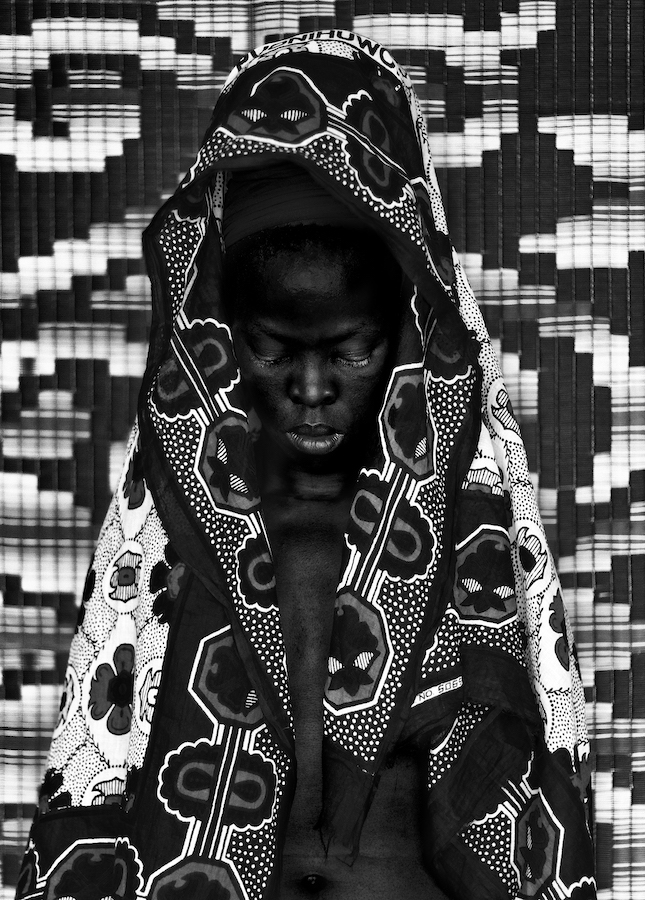

“In each photograph that I take, there is longing and looking for ‘me’”, Muholi said in a lecture at the International Center of Photography, New York, in 2016. She is unabashed about the therapeutic function of her art. It’s most obviously expressed in the self-portraits she’s begun to make in recent years, which depict the artist tricked up in costumes and headgear that mimic alike the clichés of colonial travesty and the tropes of contemporary racism. In some of these photographs Muholi exaggerates the darkness of her skin, or adopts a kind of homemade exoticism: costume and headdress made of clothes pegs, for example, in an image that at first glance looks like a nineteenth-century ethnographic portrait. Or again, photographed in Amsterdam with her hair elaborately full of chopsticks: a reference to the fact black people are presumed not to care for Asian food. Her self-portraits may look as if they’ve departed from her activist past in favour of a familiar (if still political) act of photographic self-fashioning; but in truth Muholi’s artist-activism has always been about images of herself and others. Even if it is also a matter of the most arduous labour, care and unceasing advocacy.

Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama is at Wentrup, Berlin, through 24 June; her first institutional solo exhibition in the Netherlands will be on show at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, from 8 July to 15 October; and a third can be seen at Autograph ABP, London, from 14 July to 20 October

From the Summer 2017 issue of ArtReview