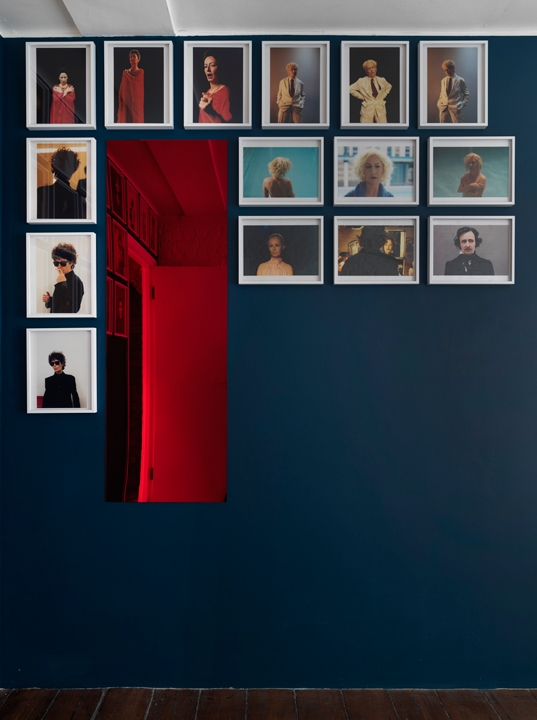

In Corvi-Mora’s entranceway, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster has hung, in cramped rows, a series of 30 photographic portraits from her ongoing Apparitions series (2012–). Self-portraits – but not quite – they show the artist disguised as iconic figures from Edgar Allan Poe to Bob Dylan to Marilyn Monroe. The artist strikes a pose, hams it up (Gonzalez-Foerster has acknowledged the debt to Cindy Sherman, though one feels there is more affection in her depictions than in the American artist’s grotesque archetypes). Installed among them is a red-tinted mirror, placed so the visitor may greet their reflection. And that is pretty much all there is to Gonzalez-Foerster’s solo show, an artist otherwise known for her largescale, often theatrical installations. Turn the corner into the main space and the gallery is empty of objects other than a potted palm seedling, no more than a few centimetres high, enjoying the sunshine on the windowsill.

On the wall and ceiling however are little islands of writing, applied in vinyl, five discrete paragraphs in total (Textbau, 2018). Read them clockwise and one can follow a stream of anxious consciousness ruminating on the damage man is inflicting on Earth, a longstanding subject for the artist (her 2008 installation in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall for example imagined London in the aftermath of an environmental disaster). ‘how does it feel to be human, an invasive group which destroys its environment in a systematic way, lost landscapes, dry gardens, birds and insects gone,’ it begins (the lack of capitalisation at the start of the sentence a trait of these texts).

Assuming these words are authored by Gonzalez-Foerster, and reflect her true feelings, the source for her apparent anxiety seems to be guilt, a suspicion that artists are only exacerbating the planet’s environmental problems through their production of objects. ‘why is it more important to think about art than take care of plants or living things. in what way is art adding something to biodiversity or rather threatening it?’ Gonzalez- Foerster writes. ‘like destroying a forest to build an opera in which a forest might appear on stage.’ She has a point: her work, for example, was shipped to nine different exhibitions in 2017, from Shanghai and Berlin to Saskatoon. That’s quite a carbon footprint, feeding the artworld’s appetite, before even considering the energy put into the production of new work.

Yet this is not the only way in which this exhibition is troubled by art. The text goes on to define art as not only representing one’s consciousness (a mode of self-reflection for both the artist, which brings me back to those photographs of Gonzalez-Foerster’s presumed heroes, and the viewer, which brings me to the mirror) but as something toxic to the artist’s health. In the runup to an exhibition (or nine), art becomes, in the same way humans are a plague on the planet, a disease that ravages Gonzalez-Foerster’s every waking moment. ‘i can’t really decide if i should continue to develop the (art) monster,’ she concludes. This largely dematerialised essay-as-show, then, reads as the artist’s response to a crisis of conscience, born out of the realisation that we have aligned art with a capitalist mode of production, a fever, both physical and mental, that has swept the world.

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster: Intensité Assouvissante at Corvi-Mora, London, 13 April – 16 June 2018

From the Summer 2018 issue of ArtReview