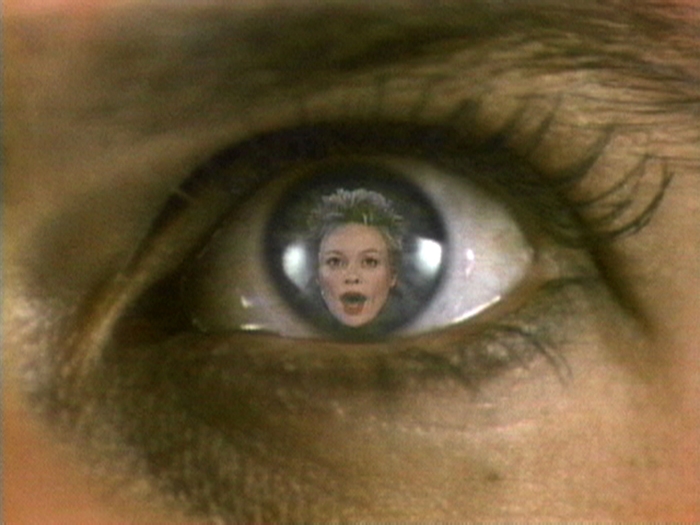

On New Year’s Day 1984, using a conference link between a PBS station in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and in collaboration with broadcasters in Germany and Korea, Nam June Paik broadcast Good Morning, Mr. Orwell to 25 million people across the world. Now accessible via YouTube, the hourlong television programme was, in the artist’s own words, a compilation of ‘positive and interactive uses of global media, which Mr. Orwell, the first media prophet, could never have predicted’. Testament to Paik’s belief (contra Orwell’s 1984, 1949) that art could break down geographical and cultural barriers, this variety show combined live and recorded sections and showcased musicians such as Laurie Anderson and Peter Gabriel alongside Salvador Dalí, Joseph Beuys and Paik’s mentor, John Cage. The effect was to take the avant-garde out of the gallery and onto a medium more commonly associated with mass entertainment, the revolutionary potential of which was dismissed by social theorists including Guy Debord, who, in Panegyric (1989), called television a weapon for the ‘constant reinforcement of the conditions of isolation of “lonely crowds”’.

Televisions had featured heavily in Paik’s work since the beginning of his career as part of the Fluxus movement in West Germany (to which he had moved from Tokyo, the city to which his family had emigrated during the Korean War, to study music history) alongside Wolf Vostell, another pioneer of the medium. In Exposition of Music – Electronic Television (1963), he laid 13 ‘prepared’ TVs on their sides, their reception detuned so that the static was presented as a constantly shifting work of audiovisual art. The work displayed the influence of Cage in encouraging its audience to attend to images and sounds that they would normally disregard, while the composer’s advice that Paik explore Buddhist philosophies in his work can be identified in Zen for TV (1963), which reduced the TV picture to a wavering vertical line. Participation TV (1963/98), meanwhile, made the medium interactive, allowing viewers to modify a set of lines that appeared on the screen by speaking into an attached microphone, the signals from which were turned into visual line formations by an integrated sound-frequency amplifier.

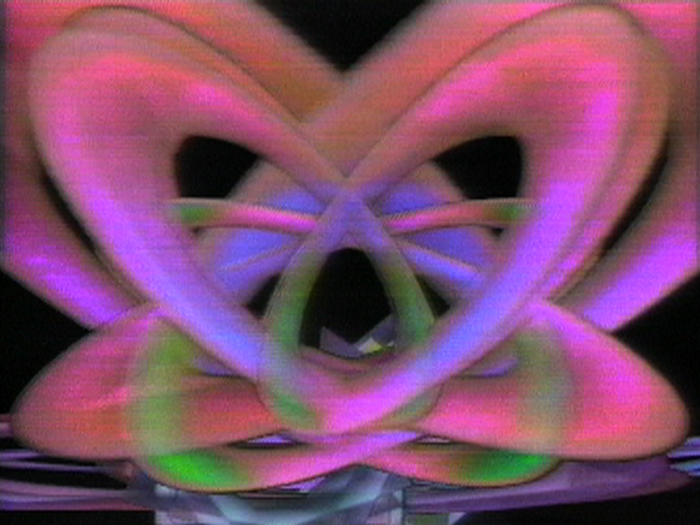

Paik was a craftsman in his medium – during the late 1960s he built a video synthesiser with TV technician Shuya Abe that allowed him to mix seven different colours received from seven cameras into a single image – as much as a media theorist, famously coining the phrase ‘electronic superhighway’ in 1974. These experiments advanced the potential of telecommunications as a two-way system and challenged the top-down, one-to-many structures of cinema and television.

The Korean artist, who died in 2006 (after having moved to New York in 1964), lived to witness the invention of the Internet and the rise of broadband, but never made work specifically for distribution via digital networks. Still, it feels appropriate that his videos have been made easily available on a platform like YouTube, as well as downloadable via UbuWeb – the avant-garde repository started by Kenneth Goldsmith in 1996 in response to the marginal distribution of experimental and underground art, films and texts. But the potential for television to deliver art to a mass audience that Paik identified has remained largely unrealised. In the UK, Channel 4 continues to commission approximately 50 short artist films each year through their Random Acts strand, and artists including Grayson Perry and Jeremy Deller have recently presented documentary series on the subjects of, respectively, the British class structure and rave culture. Yayoi Kusama designed T-shirts for Nippon TV’s annual 24-hour charity fundraiser in 2013, and also participated in Peter Gabriel’s music and art videogame experiment EVE (1996). But these initiatives invite artists to work within existing televisual formats rather than invent new ones, as Paik and his contemporaries Laurie Anderson and Robert Ashley, with his 1984 TV opera Perfect Lives, strove to do; they do not aim to jolt the viewer with any formal strangeness like the brief, unannounced microdramas that Stan Douglas inserted between programmes on Canadian television between 1987 and 88.

The generative potential of unpredicted meetings is apparent in Good Morning, Mr. Orwell, which brought disparate artists and musicians together, via satellite if not in person, in new creative relationships

The live global broadcast that made Good Morning, Mr. Orwell so distinctive at the time is now easily replicated through the Internet, but the sense of event that accompanies a huge audience watching simultaneously at a determined time has been diluted, if not completely destroyed. What has been lost is something of the element of chance encounter that is so important to Paik’s practice. The generative potential of unpredicted meetings is apparent in Good Morning, Mr. Orwell, which brought disparate artists and musicians together, via satellite if not in person, in new creative relationships. In a similar spirit, many of my most powerful encounters with artist films and videos, as when I channel-flicked onto a Man Ray film on BBC Four many years ago, were made more memorable by their unexpectedness, their formal experimentation exposing the conventions of the vast majority of television programming. YouTube’s algorithms may, over time, throw up an occasional surprise for those who have trained them by watching hours of avant-garde film (though even then it may just default to alt-right ideologues), but will not bring such works to a general audience; indispensable though it is, UbuWeb is daunting for the uninitiated, with its Film & Video index providing no more than an alphabetised list of names for visitors to click through.

Social media has, it’s true, allowed for a sense of occasion to be created around works such as John Gerrard’s Western Flag (Spindletop, Texas) (2017), a real-time, computer-generated simulation of the site in Texas where a massive oil-gusher announced the dawn of the modern oil industry. The simulation ran online for a year but broke unannounced onto national television broadcasts on Earth Day in April 2017, creating the kind of disruption that Douglas had achieved in Canada three decades earlier. This interplay between Internet and television broadcasters has the potential to break through the filter bubble of social media, according to which algorithms limit our exposure to new information by guiding us towards things that our browsing history suggests we already ‘like’. Specialist accounts for artist films and videos may occasionally spring into the feeds of those who have not followed them, but these very rare intermissions have nothing like the reach provided by television. Indeed, despite the early enthusiasm for the Internet’s democratising potential in relation to new art, it can feel that the digital revolution of recent decades has ended up reinforcing boundaries between popular entertainment and works of art or communal events of the kind produced by Paik, rather than eroding them. In addition, large social-media platforms tend not just to hide artists’ work from the wider public, but also to censor them, illustrating the amount of power these companies now wield and making both Paik’s optimism and the techno-utopianism of early Internet adopters hard to sustain.

It is not hard to imagine a contemporary equivalent of Paik proposing a showcase of contemporary artists and musicians to a streaming platform such as Amazon Prime or Netflix. The political implications would be different to Paik’s use of American public-access television, or UK artists’ collaboration with the publicly funded BBC, not to mention that such companies might baulk at such largescale and potentially unprofitable projects, even if the artists had no ethical qualms about cooperating with them (a situation which in the current context seems unlikely). International coordination between large, nationally funded arts organisations could allow the creation of new works with similar scope to the New Year’s celebration, with the added bonus of operating in Paik’s spirit of working across national and cultural barriers. If the sense of event generated for Good Morning, Mr. Orwell could be recaptured, it might even be that the comments section of YouTube and the generation of memes and social media chatter could create more audience interaction than even Paik could have imagined. Something that might, with borders hardening all over the world, give cause for a little more technological optimism.

Juliet Jacques is a writer and filmmaker based in London. A retrospective of Nam June Paik’s work is at Tate Modern through 9 February 2020.

Further reading: Four artists speak about Nam June Paik’s influence today

From the Autumn 2019 issue of ArtReview Asia