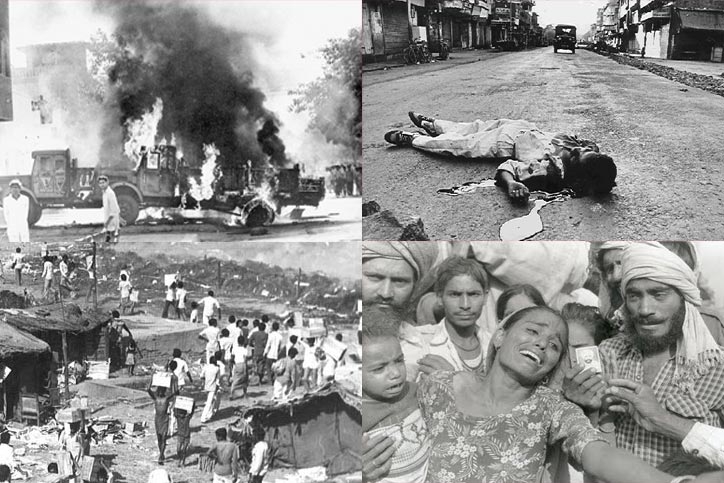

Here is an excerpt from my recently published novel Marginal Man. It is set in the India of the Indian National Congress. The present Bharatiya Janata Party regime is no better. The riots of Delhi in 1984 and the Gujarat in 2002 have one thing in common – both happened under the surveillance of the police. Now on to Marginal Man:

The house in Mayur Vihar, Delhi, was the eighth house I lived in. I was befriended by Rekhi, a twelve-year-old Sikh boy, as soon as we’d arrived. He lived on the other side of the road, near the gurudwara. His house was in Block 27.

On Wednesday, at around ten in the morning, the whole country was rocked by the news of the assassination of Indira Gandhi. At first, we thought that the prime minister’s death was just a nasty rumor, but we soon realised that the story was true. When I stepped out of the house, I was confronted with the sight of hordes of charged people in trucks and vans shouting slogans. I was told they were all heading to AIIMS, where Indira Gandhi’s body was. Some frenzied people were torching DTC buses that hadn’t made it to their depots quickly enough.

Rekhi didn’t come to our house that day. I thought of going and checking on him, but as I was unwell and tired, I decided to go the next day. I fervently hoped that riots would not break out. The assassins were Sikhs – her own bodyguards. Would the government impose curfews and issue shoot-at-sight orders? I told my wife, Nalini, to lock the doors from the inside and I went to the gurudwara to see for myself.

To my horror, I saw that four people had been set ablaze. They were still alive and running frenziedly while the mob pelted them with stones. Some were even hitting them with sticks. Suddenly, Rekhi crossed my mind and I ran to his house but it was locked.

I couldn’t sleep that night. At midnight, I watched the new prime minister eulogise Indira Gandhi on television. “The late prime minister was not just my mother; she was mother to the entire nation. In this difficult moment, let us remember the words of our mother, who said ‘Don’t kill other people. Kill the hate you feel towards other people’, and maintain peace and observe patience. Let us show the world what Bharat’s culture is.” This he said calmly and clearly. (However, the very same man, when asked about the riots at a later date, said, “When a big tree falls, the earth shakes”.)

At daybreak, I got out of bed and made my way to Block 27. Charred bodies lay in front of the gurudwara while hundreds of people shivered inside it in the bitter cold, huddled together. A deathly silence hung over all the houses, most of which were locked.

The radio news said that army units had been dispatched to places where riots were expected to break out. A curfew had been imposed and the situation was said to be under control. But I saw neither cop nor soldier even after two hours.

Some extraordinary slogans were heard by the mob that had come to pay their last respects to the prime minister in Teen Murti Bhavan. “Who murdered India’s daughter? We shall wipe out that race!”

***

“Someone’s at the door. Let’s go see who it is,” Nalini said.

It was Rekhi and his mother. As soon as I’d let them in, I closed the door and locked it.

The army and the police showed up the next morning but they were no match for the rampaging mobs that kept arriving in jeeps. This time, the mobs didn’t go banging on people’s doors. They went to the ration shop and summoned the owner. They got him to open the shop and take out the register which contained the names of the ration-card holders. They identified all the Sikhs from the register and took down their details. I was standing in the crowd and watching this unfold. Then I realized with a shock what they were planning to do and what was going to happen. The mob made its way to another shop that sold kerosene. They loaded drums and tins onto the jeeps.

In the afternoon, the army conducted a march-past. Thirty minutes after it was over, the jeep mob returned to Mayur Vihar. Addresses in hand, they went from house to house, dragging Sikhs out and setting them ablaze. When the people who lived next door to us declared they were Punjabi Hindus, the mobsters refused to believe them. The madmen were still not convinced of their religion even after they were shown the puja room. One of them asked haughtily, “Who is Darbara Singh?” Immediately, the man of the house said, “He is the owner of this house and lives in Tilakpuri.”

“You should have mentioned that first, my friend,” he said.

They came to our house next. Before they had the chance to say anything, I summoned Rekhi and Harpreet and said, “This is my sister-in-law. Her name is Bindiya. My brother is in the army; he had a love-marriage. This is their son Rakesh. As my brother is in Agra on special duty, they are staying with me and my wife, Nalini, and our daughter.”

He turned to me and said, “Madrasi babu, a girl from our village has come to your house. I hope you haven’t lied to me. If I find out you have, you won’t be spared.”

With this warning, they left.

That night on TV, the commissioner of police announced, “Today, around 15 people have lost their lives, but the situation is under control.”

The BBC reporters reported that on that very day, the worst of the killings had happened. Two hundred bodies were lying in the Tees Hazari police morgue; a thousand Sikhs had been killed in several parts of East Delhi; another thousand had been massacred in West Delhi and almost the entire male Sikh population had been wiped out. Even the trains were full of corpses. Except for New Delhi, there seemed to be no police or army presence anywhere.

In the morning, I went to Trilokpuri. The roads were littered with bodies of Sikhs who had been burnt or beaten to death. The remains told me that there were also those who had been hacked to pieces. The houses in Block 27 – Rekhi’s included – had all been burnt black.

When I reached Block 28, I saw army trucks driving away with more bodies. It was then that I saw a curious structure that resembled a shed – or did it resemble a tent? I really didn’t know how to describe it to myself or to anyone. It had obviously been constructed with scant resources – wooden boards covered with tarpaulin. Where there were no wooden boards, there were sheets of tin. There was also a barbed wire fence. The thing must have been torched the previous day. The army personnel, who I’d assumed were accustomed to pathetic sights, were themselves staring in shock and disbelief at the fully gutted tent. I walked towards it as I needed a closer look. The tarpaulin had been burnt and the roof was open.

Two small children were sitting on a set of planks that was precariously held up by sticks. Their heads were on their knees and they were hugging their legs to their chests. One of the children was around four and the other was probably a little older, six or seven maybe. They were dead, burnt. I was looking at their charred bodies; I was looking at how they died. A young solider covered his face and began to weep while another soldier kicked open the burnt door. Inside stood the charred corpse of a sixty-year-old man looking up at the children with one arm raised.

I returned home, numbed by all that I’d seen. I didn’t tell Rekhi or his mother that there was nothing left of Block 27.

“The leaders in Teen Murti Bhavan must have dispersed. I think things will be better tomorrow,” I was telling Nalini when we heard a light knock on the door.

Wondering who could be knocking so gently, I went to the door and opened it to find the mobsters standing there. “So, Madrasi, you thought you’d take us for a ride, huh?” one of them barked, slapping me hard across the face.

“Hey man, leave the madrasi,” said another one. “Where is sardar?”

On hearing this commotion, Rekhi and his mother came out of the room. A mobster caught Rekhi by the neck and threw him with such force that he landed against the wall and broke his nose.

“We will celebrate Lohri [festival] here itself!” said one fellow with a tin in his hand.

“No brother, we don’t have enough petrol. There are four other people in the street. We don’t want to burn them off one by one and waste the petrol, do we?”

Saying this, he picked up Rekhi, who was stuporous, and threw him into the jeep. The rest of the mob hopped onto it.

Rekhi’s mother and Nalini tried chasing the jeep. I ran after my daughter who had run out to follow them. I picked her up and we stood there, frozen.

Marginal Man is published by Zero Degree Publishing.