Thailand has the reputation of a fun-loving country. Its people, so the stereotype goes, crave their daily dose of amusement, as indicated by the punning that permeates its written and spoken language, particularly in popular television and film comedies. But humour in Thailand is largely limited to ordinary citizens poking fun at each other; anything that needles those at the top is a risky proposition under the strong-arm rule of the current junta.

Of our putsch-installed leaders, the current prime minister, Prayuth Chan-ocha, is regarded as one of the funniest. But his is a bully’s sense of humour, trading on intimidation and abuse rather than on wit. He made international headlines in January when he plonked a lifesize cardboard cutout of himself in front of journalists because he wasn’t in the mood to be interviewed. Some local media outlets praised the antic as ‘clever’, but what kind of society celebrates a dictator who shirks his duties by insulting people’s intelligence? One so accustomed to submission that it is willing to go along with a prank at its own expense.

The amount of public space a society allows for humour that lampoons its leaders is a measure of its freedom

The amount of public space a society allows for humour that lampoons its leaders is a measure of its freedom. The history of authoritarian regimes tells us that dictators do not appreciate satire. Since Thailand’s most recent coup, in 2014, no humour of this sort is visible in the country’s mainstream media. Newspapers still run the political cartoons that, once upon a time, used to exert real influence, but these are the work of an older generation that employs such tired, repetitive gags that its targets are no longer ruffled by them. More importantly, it neither speaks to the liberal spirit of the younger generations nor serves to unite people weary of the junta and its broken logic.

But Facebook, which is widely used in Thailand (according to Statista, as of April 2018 the country has 52 million registered users, the eighth highest number in the world), has come to provide an alternative platform for political satire. Postcoup, two standout political-cartoon pages have emerged on Facebook and proved wildly popular, judging by the numbers of ‘followers’, ‘shares’ and references to them in various social contexts. Those two pages, both with anonymous creators, are Manee Mee Share and Kai Maew.

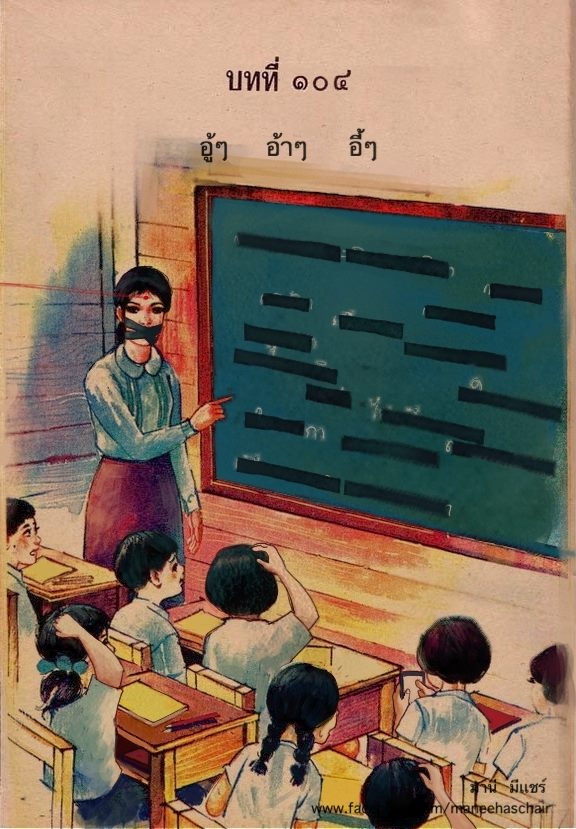

Manee Mee Share put out work in earnest between 2014 and 2016. Its name requires some unpacking. Manee is the name of a pigtailed girl character in a classic series of elementary-school textbooks, familiar to Thais who attended primary school between 1978 and 1994; ‘Share’ is a play on the way Thai people pronounce the English word ‘chair’; and ‘Mee’ is the Thai word for ‘have’, so the page’s name, in one sense, means ‘Manee has a chair’ (its English handle is @maneehaschair). The chair is an allusion to the 1976 Thammasat University massacre, in which the government used violence to suppress student protesters gathered at the university and the nearby Sanam Luang Square, leaving 46 dead. (The demonstrators were protesting the return of former dictator Thanom Kittikachorn, who had been driven into exile following an uprising three years earlier.) The far-right media at the time accused the students of lèse-majesté and, as a result, a considerable number of people said good riddance to the casualties. An American photographer from the Associated Press, Neal Ulevich, photographed a man with a metal chair raised above his head, ready to smash the corpse of a student hanging from a tree, a crowd looking on. The photograph became emblematic of that harrowing chapter in Thai history, a reminder of the impunity with which the far right inflicted violence that day. The reference to that chair in the name of Manee Mee Share connects the country’s current political problems with the forces that gave rise to the 1976 massacre. Evidently well-versed in political history, Manee Mee Share’s creator relies on more than just humour in his cartoons. Nobody knows why the page ceased activity in 2016, but in a country described by the most recent ‘Freedom of the Press’ report as ‘aggressively’ enforcing defamation and lèse-majesté laws, having ‘banned criticism of its rule, and harassed, attacked, and shut down media outlets’ while arbitrarily detaining and arresting journalists, it’s not hard to see why the cartoonist might fear to continue.

The creator of the newer Kai Maew (literally ‘Cat’s Eggs’, slang for ‘Cat’s Testicles’) on the other hand is, according to an anonymous interview with the news site Prachatai, someone with an art background, relatively apolitical until he or she could no longer sit through the injustice that manifests ever more clearly. Kai Maew first appeared on Facebook in 2016 and disappeared temporarily around January 2018, prompting its more than 400,000 fans to worry that the page had been shut down by the military and that the artist behind it might be in danger. But soon a page called ‘Kai Meow X’ (@cartooneggcatx), with the same creator, showed up in its place, and has already garnered over 200,000 followers.

In Thailand, humour is not yet an effective weapon against dictatorship. It merely takes the edge off the frustration, letting us laugh, however wearily, at the decline of our freedom

Kai Maew’s pen strokes are simple, one could say ‘rough’, whereas Manee Mee Share very closely replicates the style of the drawings in the original textbooks. The illustrations have the more contemporary feel of Japanese manga or comic strips. The page also uses characters that resemble people in the news: its main character is a man in military uniform with a Hitler moustache, obviously personifying a military dictator. Unlike Manee Mee Share, which adheres to a very specific style, Kai Meow has fewer aesthetic restrictions, so is able to adapt its illustration style to the punchline or material at hand. It has used wordless panels (most of Manee Mee Share’s jokes are verbal) and draws on pop culture, which has given it broader appeal. While Manee Mee Share’s core fanbase is the well-educated left, Kai Maew has followers of different political persuasions, and has managed to avoid being labelled as part of the ‘Down with the Monarchy’ machinery dreamed up by the far right for its witch hunt. Kai Maew has pulled all this off despite its association with Somsak Jeamteerasakul, the exiled academic much maligned by the conservative faction of society because of his vocal critique of the Thai monarchy (not only does he have a lookalike character, he also wrote a foreword for Kai Maew’s cartoon collection, published by Prachatai Press in March 2018).

Even though Facebook has made pages like Manee Mee Share and Kai Maew possible, the fact that their creators are forced to hide behind anonymity and may have to go dark at any time demonstrates that, in Thailand, humour is not yet an effective weapon against dictatorship. It merely takes the edge off the frustration, letting us laugh, however wearily, at the decline of our freedom.

If the status quo continues, especially if the election slated for the beginning of 2019 (and postponed since 2015) does not materialise, the cartoon pages on Facebook may no longer be able to bear the weight of people’s disgruntlement. Then it might be time for us to study the playbook of the Otpor! student group from Serbia, which, through its use of humour as a peaceful means of protest, played a pivotal role in ousting Slobodan Milošević in 2000. Srđa Popović, an Otpor! leader, wrote about the group’s tactics in his 2013 essay ‘Why Dictators Don’t Like Jokes’: ‘These acts move beyond mere pranks; they help corrode the very mortar that keeps most dictators in place: Fear’.

In Thailand, fear still looms over the laughter elicited by cartoons like Kai Maew, and who knows if we have ever laughed freely and truly, given our long and nearly unbroken string of authoritarian regimes.

Translated from the Thai by Mui Poopoksakul

From the Summer 2018 issue of ArtReview Asia