The movement has been flattened into a shorthand for feel-good, guilt-free opulence, which elides its complexities and contradictions

This year marks the centenary of Art Deco. Well, that’s not strictly accurate, but much neater than ‘the centenary of the 1925 Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes’. It was then and there that something approaching a stylistic movement would coalesce, bringing together designers as varied as Lalique, Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann and even Le Corbusier under the banner of modernity. In reality, though, ‘Art Deco’ – the term only popularised by the critic Bevis Hillier as late as 1968 – was far from being unified. It drew upon many different visual referents, from neo-classicism to Cubism, and was manifested in many different social and political contexts. In fact, the cultural bricolage of Art Deco is not so far from our contemporary experience of visual culture, in which a bewildering array of ‘cores’ and ‘aesthetics’ are constantly emerging in response to social trends and colliding on social media where they can be appropriated and reimagined yet again.

Our understanding of Art Deco has been mediated by popular culture in a way that few other aesthetic movements have and, as a result, flattened into a kind of shorthand for feel-good, guilt-free opulence, all cocktails and jazz. Hillier’s book Art Deco of the 20s and 30s presaged a 1970s Art Deco revival, as expressed in the interiors and fashions of Biba and the 1974 film adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (published in 1925, the same year as the Paris Exposition.). In the next decade Agatha Christie’s Poirot and Jeeves and Wooster brought Art Deco onto the small screen, in their animated opening sequences and meticulous set design: an exercise in cosy nostalgia for a lost interwar golden age. Today, the Art Deco movement has been relegated to a middlebrow signifier of good taste, the stuff of wedding stationery and hotel lobbies. This elides the contradictions and complexities of the movement, obscuring its origins at a crucial moment in the formation of modernity.

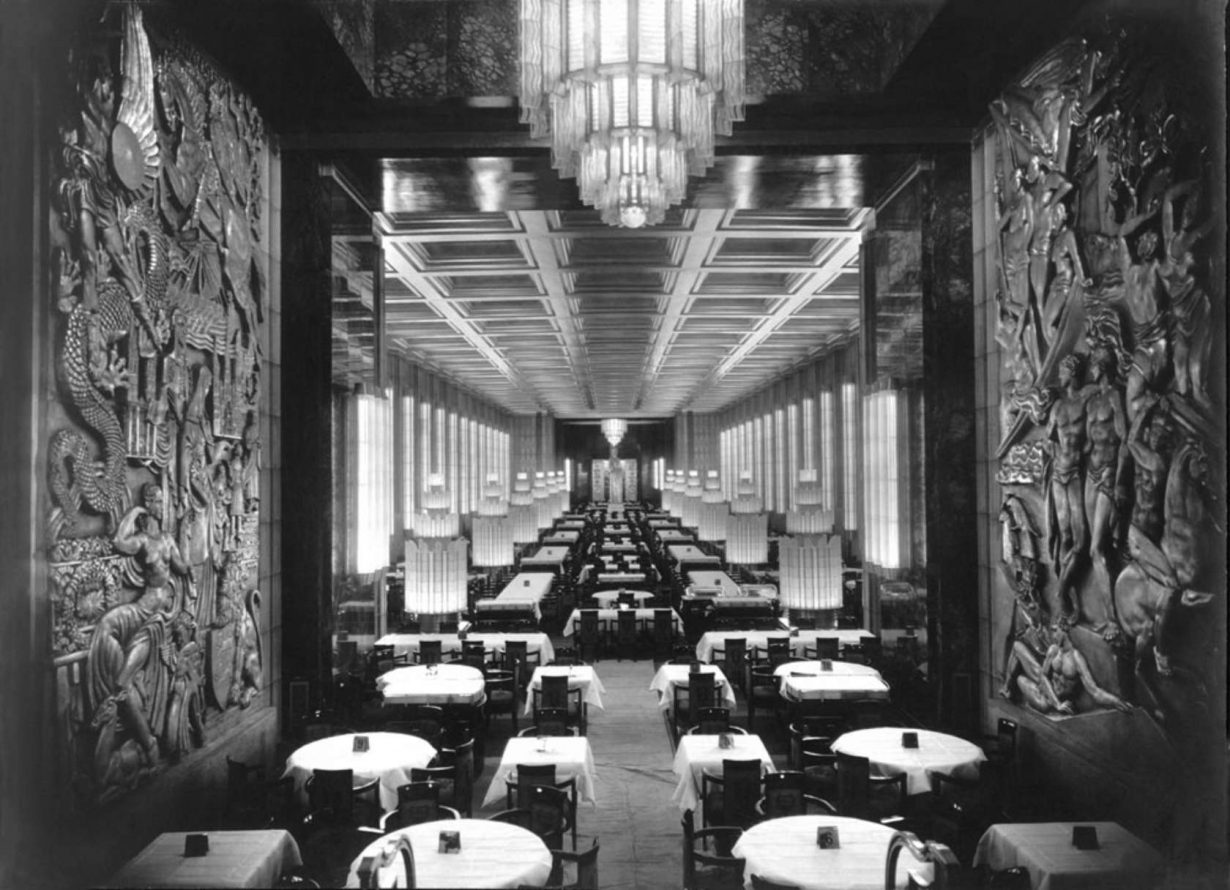

But first: what was it, if not a cohesive style? It was ornate, but in a symmetrical, geometric manner, rather than the sinuous floral curves of Art Nouveau. It was highly embellished, though its later evolution into Streamline Moderne style – characterised by clean, curved lines and unembellished white walls – is the more recognisable iteration today. The ornate characteristics of Art Deco design showcased the finest handcraft and rare materials from an international range of sources, aided in part by the extractions of empire – ivory, ebony and diamonds from sub-Saharan Africa, teak wood from India, jade from China, lacquer techniques from Japan. Even as it championed these luxurious materials and techniques, Art Deco took full advantage of industrial manufacturing techniques. Thus, it became the approach of choice for some of the era’s most prominent industrial achievements: the luxurious ocean liner SS Normandie, the Hoover factory in London, and the Chrysler building in New York City, the latter’s silvery sunburst spire rising over the economic powerhouse of the twentieth century.

This, of course, was all the product of a colonialist endeavour, not only in its use of materials extracted from colonised lands, but in its appropriation and exoticisation of non-European cultures. Appropriation and orientalism were hardly new issues in European art and design, but the industrial underpinnings of Art Deco meant that it was the first stylistic movement to spread ‘exotic’ styles and motifs among a broad consuming public at all economic levels. The 1922 excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamen, by the British Egyptologist Howard Carter, sparked a craze for all things Egyptian which was absorbed into the movement. Thanks to widespread media coverage of the excavation and the display of a replica tomb at the 1924 British Empire Exhibition, Egyptian motifs permeated 1920s architecture, fashion and jewellery, marking the first significant Egyptian revival in Europe since the 1810s. In the US, meanwhile, popular fascination with ancient Mesoamerican cultures translated into a distinctly American iteration of Art Deco: public and commercial buildings in what would be dubbed the ‘Mayan Revival’ style included the Empire State Building (1933) in New York City, the Guardian Building (1929) in Detroit, and the San Francisco office building known as 450 Sutter Street (also 1929).

The position of Art Deco in relation to class is harder to pin down. The style was as appropriate for cinemas, the ‘picture palaces’ of the people, as it was for actual palaces – the 1930s extension of the medieval Eltham Palace is one of the finest expressions of Art Deco interior design, with elaborate marquetry designed by Peter Malacrida and Rolf Engströmer. The movement, which coincided with the ‘Golden Age’ of Hollywood, owed much to cinema, a key conduit through which Art Deco design and aesthetic was translated for mass audiences – just look at the sets on any Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers film, such as the hotel suites in Top Hat (1935), or the dance studio in Swing Time (1936). In this sense, it was perhaps the first design movement to be amplified and popularised by mass media, which could be itself consumed within a complementary environment. The cinema-building boom of the 1930s, overseen in the UK by architects such as Harry Weedon and George Coles, created opulent Art Deco buildings that were accessible to all for just the price of a ticket.

Perhaps the cinematic ubiquity of the style is one of the reasons why its objects and architecture feel so distinctly ‘period’. There are a few exceptions, of course. The Anglepoise lamp (designed by George Carwadine in 1932), for example, or Eileen Gray’s E1027 table (1927) have both achieved the status of timeless design classics. A hundred years later, though, the legacy of Art Deco rests less on its influence over contemporary design, and more on its deployment as a retrofuturist setting for film, television and video games. The heyday of Art Deco coincided with the emergence of science fiction as a distinct media genre, with the introduction of comic book characters like Buck Rogers (1929) and Flash Gordon (1934), and Fritz Lang’s vision of a dystopian future in Metropolis (1927). Later productions have reverted to Art Deco tropes as a means of signifying the threat posed by technology and industrialisation, mirroring many of the concerns which characterised the 1920s and 30s: the threats of fascism and war, the atomisation of urban society, and the rise of political extremism prompted by gross economic inequality. You can see this in everything from the gritty Gotham City of Tim Burton’s Batman (1989), the violent opulence of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985), and the influential cityscape of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), to the stylish airborne fantasy Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004) and the post-nuclear bunker society of Bioshock (2007). Art Deco may not be the future of design, but it still influences the design of retrofuturism.

Danielle Thom is senior curator at the Design Museum, London