Amidst Russia’s criminal invasion, the destruction of lives goes hand in hand with cultural devastation

Russia’s criminal invasion of Ukraine – now entering its fourth week – has brought unparalleled destruction. Alongside residential buildings, schools, children’s hospitals, and maternity wards, the Russian missiles have not spared Ukraine’s landmarks and museums. In a perilous situation, Ukraine’s art workers have united in their efforts to protect the country’s cultural heritage. They’ve snatched artworks from fires, driven for days with installation pieces in the trunk, and reinvented galleries as sanctuaries.

In doing so, these people have drawn upon an acute sense of duty to save not merely Ukrainian artworks, but a broader, more expansive heritage situated in the country. In the aftermath of intense Russian airstrikes, the Kharkiv Fine Arts Museum suffered substantial damage, exposing its exceptionally diverse collection to the elements. The museum’s staff strove to secure artworks by Early Netherlandish, Indian, Chinese, French, Italian, and Russian artists amidst indiscriminate shelling and the unnerving sight of corpses on the streets. As Kirill Lipatov, the director of science at the Odesa Fine Arts Museum, recently said, it is scarcely possible to grasp the fact that Ukrainian museums are now saving Russian masterpieces from Russian aggression.

The destruction of lives goes hand in hand with cultural devastation. In Chernihiv, a city on the verge of humanitarian catastrophe with no heat, electricity, or safe escape routes for its residents, Russian missiles destroyed the Vasyl Tarnovskyi Museum, a fin-de-siècle architectural monument; the whereabouts of its collection are as yet unknown. In besieged Mariupol – a city in which a six-year-old girl died from dehydration in the ruins of her house – Russian soldiers shelled the mosque of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and his wife Roxolana, while more than 80 people (including 34 children) sought refuge inside. Yesterday, bombing obliterated the city’s Donetsk Regional Drama Theatre, in which more than a thousand women and children were sheltering (and despite the word ‘children’ written in Russian outside the building, and visible from the sky). As the thunderous noises over Kharkiv – a city already encrusted with rockets – portend continuous wreckage, terror, and mass murder, locals now desperately seek to keep the location of shelters a secret from the invaders.

Critical losses of indispensable art accompany Russia’s delirious ambition to recreate its former imperial borders and impose ‘the Russian world’ at any price. Western accounts frequently display an alarming lack of understanding of Ukrainian history and culture. The first reported destruction of cultural heritage – the fire that razed Ivankiv’s Museum of Local History to the ground – ignited a rehearsal of familiar ignorance. The attention on the artworks of Maria Prymachenko, stored at the museum and rescued from the fire by the staff, inevitably recited praise for her work expressed by canonised male figures – namely Pablo Picasso. Evidently, recent endeavours to deconstruct cultural and geographical hierarchies fail to encompass Ukraine. Discussions of East-Central European art scenes often reprise the problems of budget constraints and – derisively – a lack of specialists, as well as the adversarial closeness between Russia and Ukraine (a discourse which translates into a universalising of Russian experience in historical, especially Soviet-related, studies).

In fact, Prymachenko’s creative trajectory exemplifies how Ukrainian art was tamed during Soviet times: conveniently wrapped around subsidiary categories of ‘folk’ and ‘national,’ to be displayed as the ‘adorable scribbles’ of the ‘brother nation’. But Prymachenko spent her life in the Ukrainian village of Bolotnia, diligently teaching future generations of Ukrainian artists, including her son Fedir and her grandson Ivan. She sought to provide an alternative to the state education which proclaimed Russian art as the cradle of creative brilliance – an inspiration to art workers who dared to challenge this facile genealogy.

Sensitive to this history, the country’s art scene has come together to protect cultural heritage, put on the line as the carnage continues. Olha Honchar, the director of the ‘Territory of Terror’ Memorial Museum of Totalitarian Regimes in Lviv, initiated the Museum Crisis Center. The venture links museum personnel with international funds and provides various kinds of support to cultural institutions all over the country. Her approach prioritises the safety of the staff members. Honchar told me:

‘While the museums in the West of Ukraine currently are in more fortunate positions – we provide packaging and fire extinguishers to them – the museums in the zones of atrocious military actions have the most basic needs: their teams are deprived of money for food and medicine. At this stage, it is of utmost importance to support those people who subsequently will preserve the heritage. If we don’t secure their basic needs, there will be no living beings to receive the fire extinguishers and packaging.’

The initiative now relies on financial support from the European Commission (within the project ‘Force is Here,’ implemented by the NGO Insha Osvita), the Pinchuk Art Centre, MitOst e.V., and private donors. During the first 15 days of operation, the Museum Crisis Center provided help to 36 cultural institutions, including 13 museums in the Luhansk region and 10 organisations in the Donetsk area. In addition, Honchar highlights the invaluable work of her peers in Kyiv: the Visual Culture Research Center and the Ukrainian Emergency Art Fund, set up by the Museum of Contemporary Art NGO in partnership with the media outlet Zaborona, Mystetskyi Arsenal National Art and Culture Complex, and the contemporary art gallery The Naked Room. Maria Lanko, the cofounder of the gallery and cocurator of the Ukrainian Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale, recently recounted to me:

‘On 24 February, after the first explosions, I put the funnels [an essential part of the installation to be exhibited in Venice] in the trunk, hopped into my car with a suitcase, prepared for a two-day exhibition visit in Dnipro with a couple of garments, and drove for more than five days in total to get the artwork beyond the border. Now our team works relentlessly to secure the gallery’s collection in Kyiv that includes the key works of Oleh Holosiy (1965–1993) we must protect.’

The volunteering efforts of art workers extend beyond professional communities. The Territory of Terror team donated equipment and furniture for shelters. Lviv Municipal Art Center has reinvented its gallery spaces into a community centre for refugees from eastern and central Ukraine. The Yermilov Arts Centre in Kharkiv (strikingly named after the Ukrainian avant-garde artist expunged from art-historical narratives during the Soviet era, and studied later by Ukrainian art historians in secret) serves as a bomb shelter for the Kharkiv National University. Many artists there, including Pavlo Makov, the author of the aforementioned Venice project, spent days and nights there while Russian rockets rained down on the city. The project space Asortymentna Kimnata (Assortment Room) in Ivano-Frankivsk, which still runs workshops, is working to support the evacuation of art archives. These efforts notwithstanding, private collections, especially those in the custody of artists’ families, endure the most hazardous conditions.

As Russia’s army forges ahead with its appalling bombardment, deliberately targeting residential houses and civil infrastructure, an artistic legacy – of world-historical importance – remains in grave peril. In Ukraine, each day of this war reveals the vital interconnections of corporeality and creativity. For the sake of art and life, undoubtedly, Ukrainian art workers will resist.

Polina Baitsym is an art historian and curator specialising in socialist realism in the Ukrainian visual arts. She is currently a doctoral candidate in comparative history at Central European University, Budapest/Vienna, and a curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art NGO (MOCA) Library, Kyiv, Ukraine.

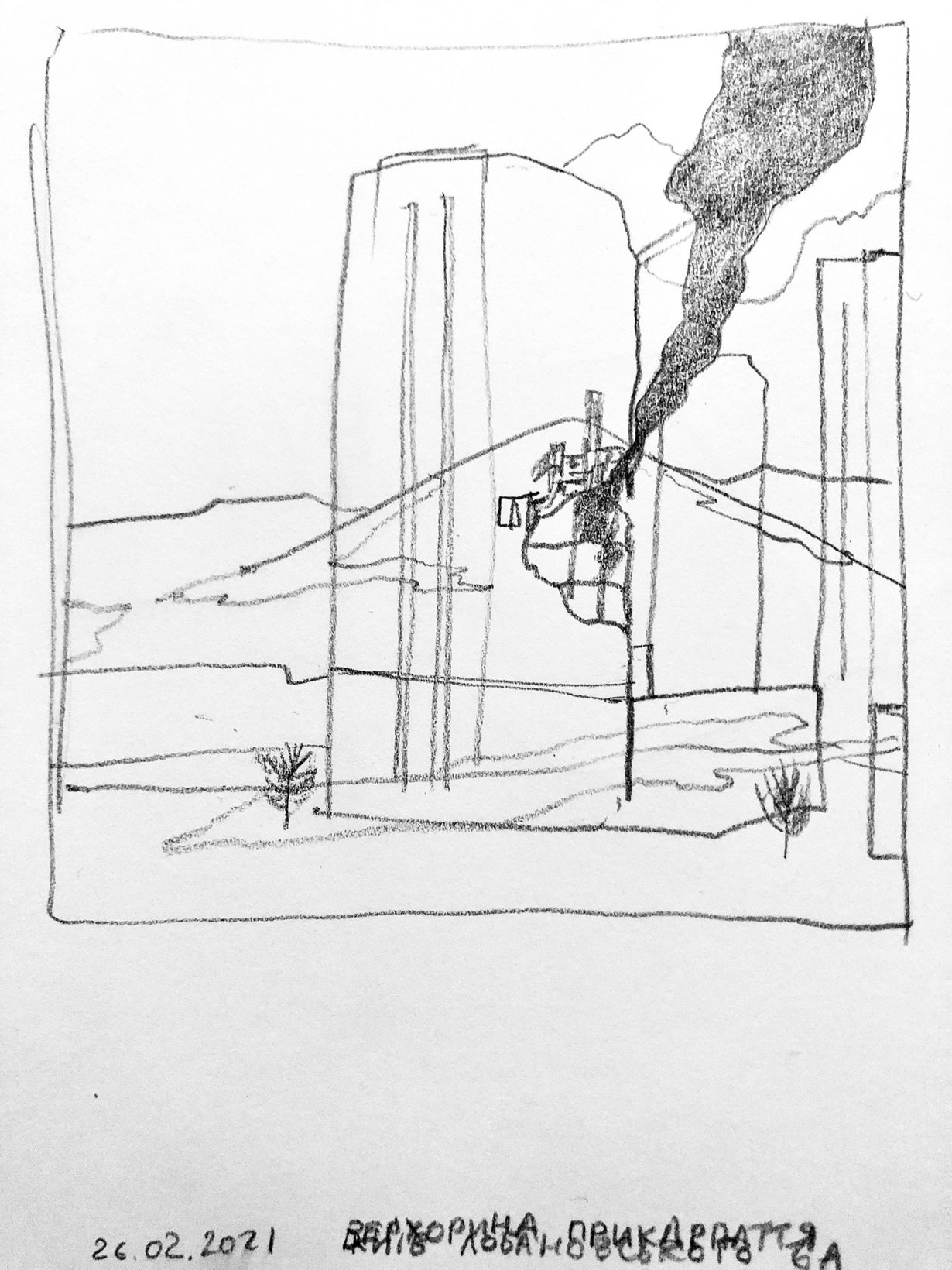

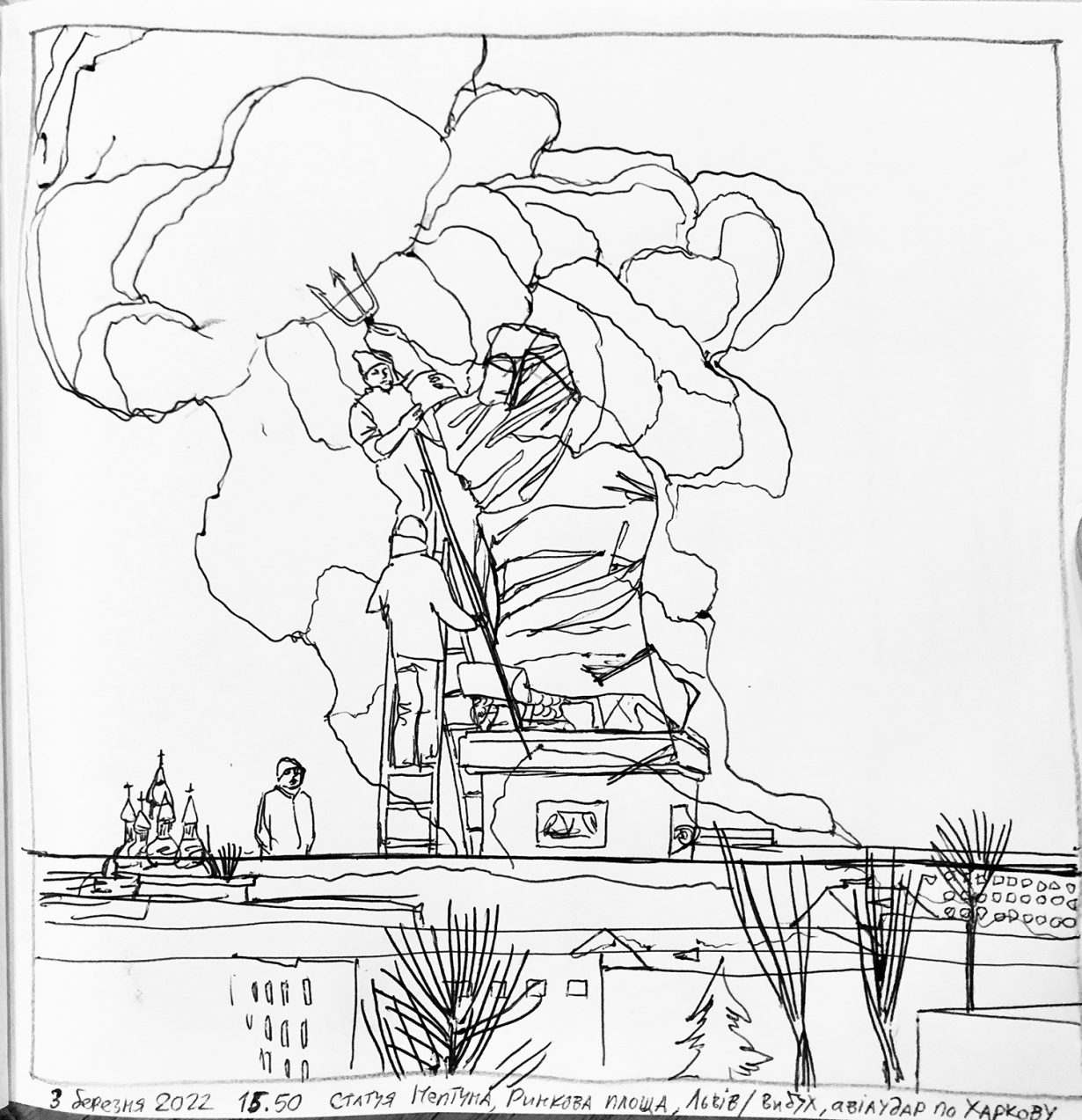

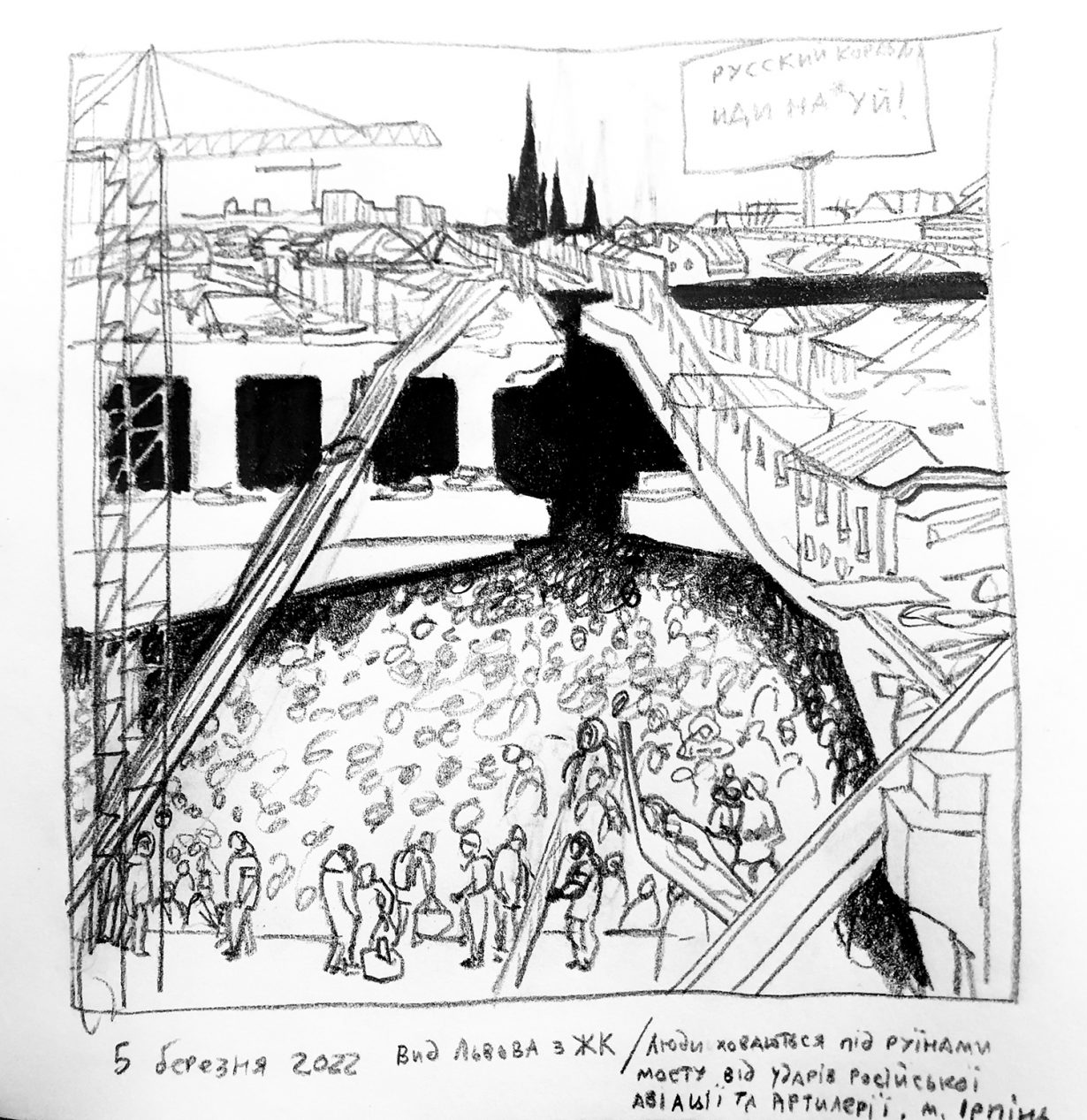

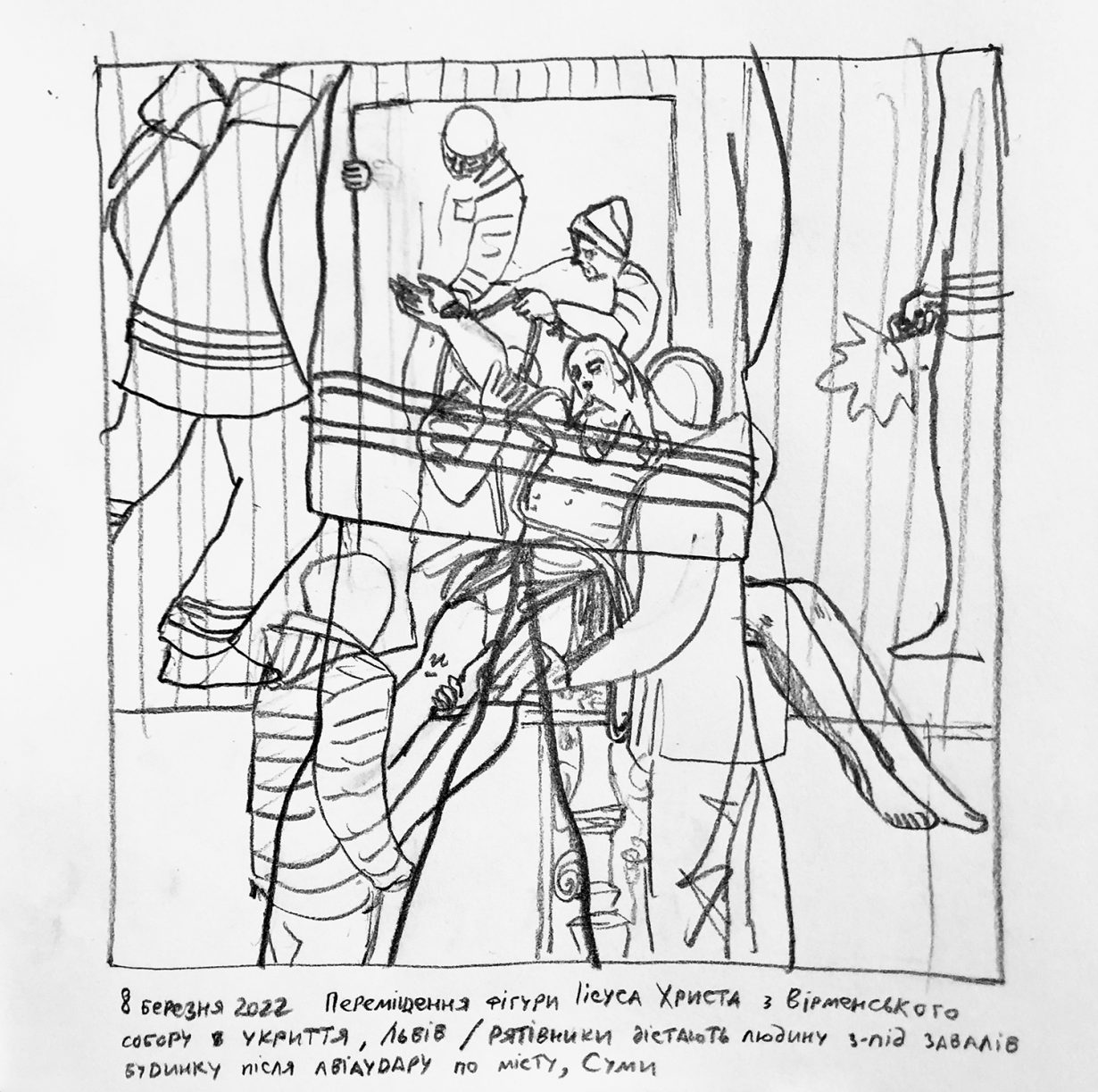

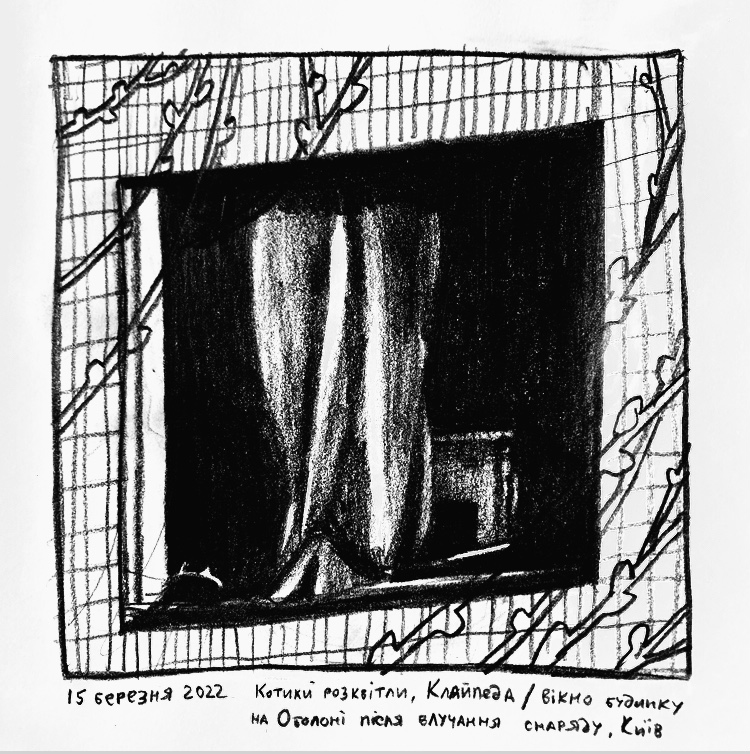

Inga Levi is a Ukrainian artist who was caught by the war in Lviv while she and her colleagues were preparing the opening of the Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit Museum in Kryvorivnia, a village of the Verkhovyna district in the Ivano-Frankivsk region. In her war-time series Double Exposure, the artist depicts an overlapping of two accounts – the scenes she witnesses while navigating relatively safe routes out of the country and traumatic news reports from places of belonging in Ukraine.