To mark the opening of the eleventh edition of the UK’s leading biennial and international contemporary art prize, ArtReview partners with Artes Mundi and catches up with the six international artists presenting their work across Wales from 24 October 2025 to 1 March 2026.

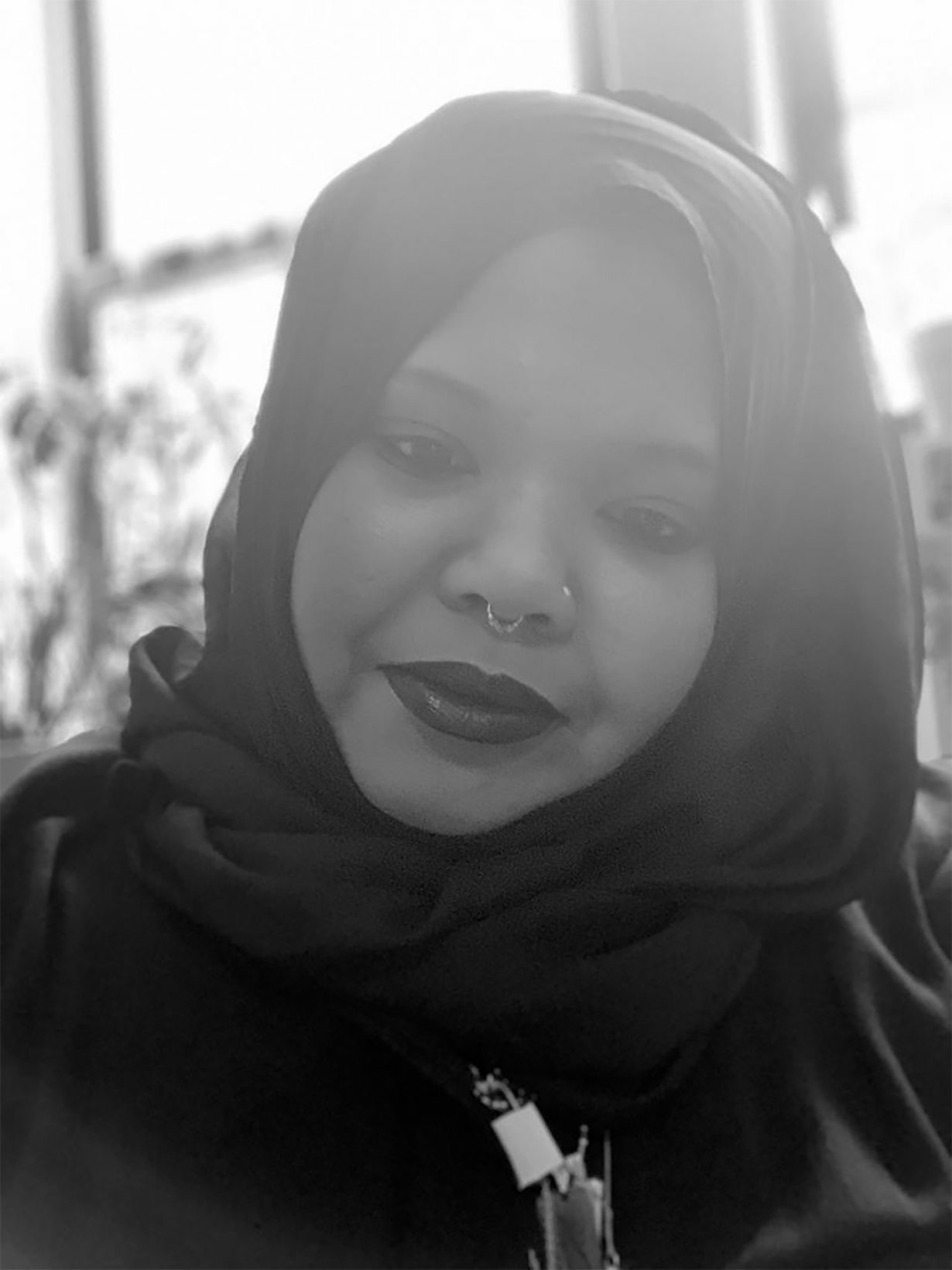

Anchored by a group exhibition at National Museum Cardiff that foregrounds ambitious new commissions and major loans, Artes Mundi 11 invites thematic resonances between practices shaped by displacement, memory and the environmental and emotional costs of political conflict, expanded through solo presentations at venues including Aberystwyth Arts Centre, Chapter in Cardiff, Glynn Vivian Art Gallery in Swansea and Mostyn in Llandudno. Platforming global perspectives on the human condition, Artes Mundi 11 continues the organisation’s commitment to socially engaged art. Among these artists is Kameelah Janan Rasheed, whose multidisciplinary practice examines the poetics, politics and pleasures of language. Working across immersive installations, public artworks, publications, performances and video, Rasheed treats language as both material and immaterial, often framing reading and writing as transgressive, even erotic acts of ingestion, immersion and estrangement. Her recent solo exhibitions include presentations at REDCAT, Los Angeles; KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin; the Art Institute of Chicago; and Kunstverein Hannover. Rasheed is also the author of seven artists’ publications and teaches at Yale and the School for Poetic Computation. She is the founder of Orange Tangent Study, which provides artist microgrants, and The Little Octopus School, an itinerant project with its own publishing arm, Scratch Disks Full.

AR How do you help audiences connect with stories that come from your own background or community? When you work with shared or inherited stories, how do you decide what to include and what to leave open?

KJR In a 2018 interview with Trinh T. Minh-ha, Erika Balsam prompts:

In your first film, Reassemblage [1982], the voice-over declares: ‘I do not intend to speak about; just speak nearby.’ What does this mean?

And Trinh T. Minh-ha responds:

When you decide to speak nearby, rather than speak about, the first thing you need to do is to acknowledge the possible gap between you and those who populate your film: in other words, to leave the space of representation open so that, although you’re very close to your subject, you’re also committed to not speaking on their behalf, in their place or on top of them. You can only speak nearby, in proximity (whether the other is physically present or absent), which requires that you deliberately suspend meaning, preventing it from merely closing and hence leaving a gap in the formation process. This allows the other person to come in and fill that space as they wish.

This reminder, ‘to speak nearby, rather than speak about’, has helped me build an ecosystem of thinking about the ethics of storytelling and the importance of either ventilating or crafting narratives so that they are not claustrophobic. Deciding what to include and what to exclude in an exhibition is a continual conversation about consent. Often, when I make work about my family, they are involved in some aspect, from helping with the installation process to the inclusion of their work in the exhibition to collecting water samples. At other scales of intimacy, I consider the responsibility to not speak over the diversity of experiences within my communities – that my story is exactly that: mine. And it is my responsibility to leave space for two things: firstly, the opportunity for complication, expansion, or even what Catherine Malabou talks about regarding plasticity and annihilation; secondly, in the words of Pope. L during a 2023 exhibition video, “You come and you fill the holes with your experience’’.

AR What would you like visitors to experience after spending time with your work?

Of course, I have ideas about language and power that I want to share. However, I am most excited about what happens beyond my expectations. This is where I find the most joy in being an artist: someone else seeing something that I could not have planned for or imagined.

AR Your installations respond closely to the buildings they inhabit, spilling text and images across these interior architectures. How do the spaces at Glynn Vivian and National Museum Cardiff shape the way you’re thinking about language and its gaps or ‘fugitive meanings’?

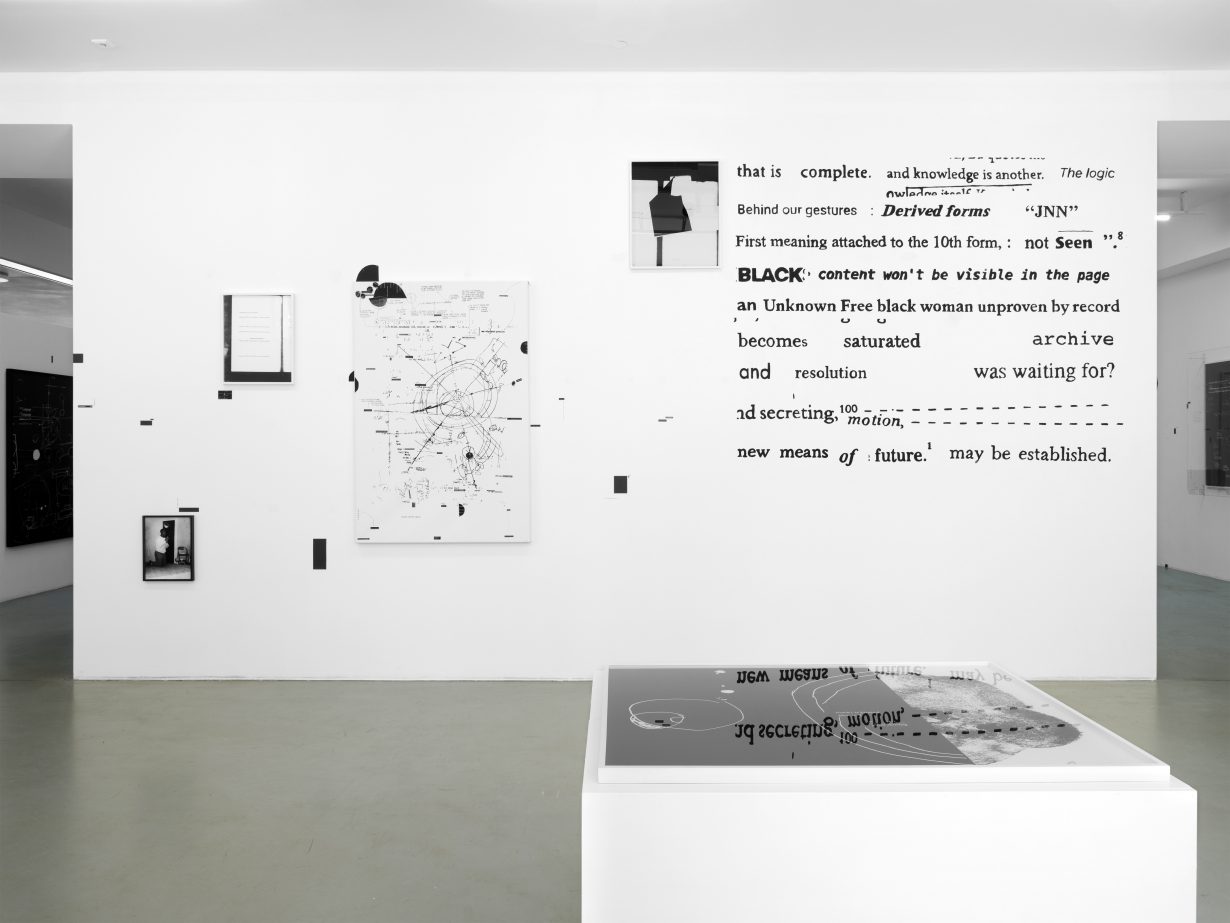

Language and architecture are both fussy containers: a sentence attempts to hold words together, while architecture tries to corral bodies and property (which are often interchangeable). Each container has its possibilities and limitations. This is what interests me most: when a container disobeys by holding more than it should or outright refuses its ‘duty’. Testing a system’s limits is speculative work: I seek edges not to confine myself, but to strategise how to escape the predictability of an increasingly predictable society. If a sentence is meant to have a logical flow, what happens when it does not? Or if an architectural site releases more than it can contain? What’s a wayward sentence or an intentionally misused site but rehearsals or studies (see Fred Moten) for future acts of collective disobedience?

I am especially drawn to architectural features like alcoves, corners and pocket spaces because they can serve as sites of compression, containment, concealment and cocooning. Linguistically, this is like writing that’s restrained, tucked away or veiled. Because of these qualities, such spaces are ideal for exploring gestures of expansion, escape and emergence. Sometimes, this appears as an absurd phrase jutting from a wall corner. Other times, it treats a corner as a lasso, pulling the viewer closer to the wall. Often, it’s language escaping its semantic and architectural container: words spilling out of the frame, dispersing through space; a banner transforming into a pool of insights; or footnotes and indices scattered throughout. Another analogy is ‘escape velocity’ – the minimum speed and direction required for a body to break free from a gravitational pull. None of this is liberation. Art objects are not substitutes for material change. Still, I believe art offers new protocols and methodologies to experiment with, until these years no longer rhyme with the others. Or as my earlier print stated, ‘Black people/want irony.’

Any installation is shaped by the affordances of the space. What is impossible is just as important as what is possible. In this way, the architecture becomes a score for the artist, curator, technicians and visitors. Even when given the opportunity to construct new walls, I do not. I find deep pleasure in demanding spaces: uneven walls, textured floors inherited from the previous factory use, non-continuous walls, low ceilings and tight corners. The demand that I develop a certain intimacy with the environment; the surface becomes a skin, to, in the words of Roland Barthes, ‘rub my language against the other.’ This intimacy is nurtured by close-reads or studies of the space: examining floor plans by redrawing them repeatedly, watching videos of people navigating the space, sitting in the interior to observe shifts in lighting and humidity, standing at different locations to identify oblique, framed, layered and blocked sightlines, and learning more about the space’s physical history. By the time the installation process ends, I have touched every surface: I know where the wall bows. I have found the seams connecting drywall panels. I figured out which corners are not square. The space I was allotted at the National Museum of Cardiff includes a large wall with painted text that crawls across the corner. I also had the opportunity to explore a space in the centre of the gallery that features eight pillars, allowing for layered sightlines. At Glynn Vivian in Swansea, my work lives in a long hall where three large banners hang from the mezzanine and spill onto the floor. The alcove features discrete works that are collaged directly onto the architecture.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed is showing work at Glynn Vivian, Swansea, and National Museum, Cardiff, through 1 March 2026