ARTREVIEW:

As one of ten shortlisted artists for Artes Mundi 6, you are presenting a project in a large exhibition, taking place across three venues (the National Museum Cardiff – the exhibition’s regular venue –and also at Chapter Arts Centre and ffotogallery), through 22 February 2015. Could you tell us a bit more about your project and what form it takes?

RENZO MARTENS:

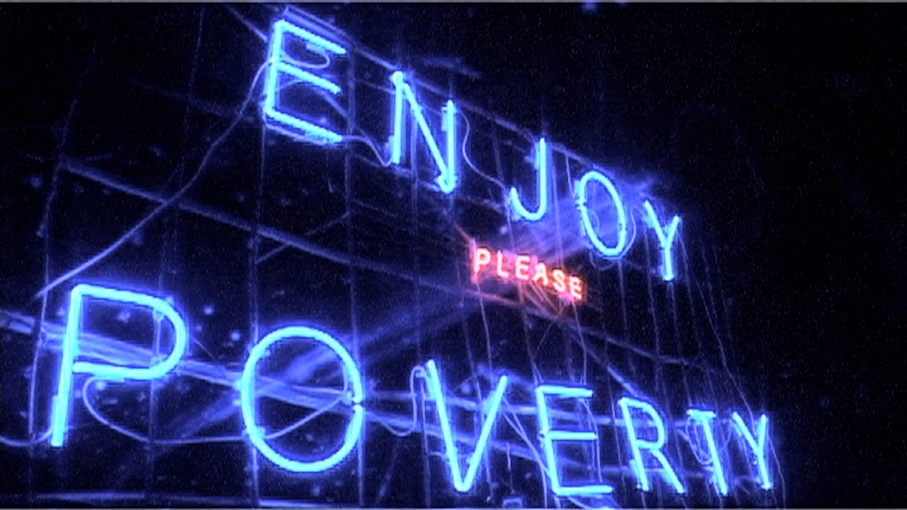

At the show, I’ve installed Episode 3, also known as ‘Enjoy Poverty’, which is the account of four years of work in Congo, starting in 2004. The piece deals with labour conditions in Congo, but especially with another issue; how the sheer poverty resulting from unpaid labour is a natural resource. Poverty can be filmed, photographed, and discussed. And from these activities the proceeds accumulate in the very same places as the proceeds of mining or plantation labour; London and New York. So the film tries to work its way through the inconsequentiality of the political claims of contemporary art, and formulate some insight into the status quo.

It should come as no surprise that the places where this film had an impact were New York, Berlin and London. So I decided that, instead of making critical films, I should build a settlement in the Congolese jungle (The Institute for Human Activities), where artists, as well as plantation workers, can start thinking through the status of art in the global economic systems we inhabit, and where institutional critique can have an economic spin-off for the people inhabiting the phenomena, and not, at least, not only, for cappuccino bar owners in the Lower East Side.

The second body of work installed consists of sculptures made by members of the Congolese Planation Workers Art League. This league was set up by plantation workers from two former Unilever plantations, and another, third plantation. Soon after, Unilever sold the plantations, the art centre I was setting up in the rainforest was destroyed by the new owner, Canadian Palm-oil plantation operator, Feronia.

It is important to stress that most of the members of the League have been working for Unilever all of their lives, and thus contributed to the funding of the influential Unilever Series at Tate Modern, featuring Bruce Nauman, Carsten Holler, Tino Seghal and others. Despite this, on the planation, few of the workers have access to clean water or electricity or any type of sanitation.

Feronia saw kids making drawings of their ideal futures as a threat, had the drawings confiscated and forced us to leave. We formed a new settlement, where plantation workers, some of them members of the league, have been making lots of self-portraits out of river clay. They’re amazing, deep and harrowing. The authors would never get a visa to come present their work in the UK, and even shipping the sculptures would be a nightmare. But we found the very cocoa that plantation workers like Nestor Mbau and Jeremy Magiela produce, located in cocoa warehouses in Amsterdam. We struck a funding deal with the cocoa operator, a company called Barry Callebaut, and we were able to reproduce the self-portraits in the very cocoa these people have been producing for global markets for the last century. Which to me makes sense, because for people like Nestor or Mbuku or Emery Muhanga, cocoa really is the only vehicle reserved for them to export and communicate with the rest of the world.

Of course, all profits go to the authors; we make critical engagement profitable for some of the people on the lowest rung of the global art production ladder.

AR: Artes Mundi aims to support ‘contemporary visual artists who engage with the human condition, social reality and lived experience’. How do you feel your work relates to that definition?

RM: I could make critical art in East London, Berlin or New York, but, in material terms, what it would do is fuel the gentrification of these areas, raising prices and pushing locals out of their homes. If I make the art centre on a Unilever plantation in Congo, and build a platform through which Congolese workers export their ideas globally, then together we create economic diversification and an alternative to badly-paid plantation labour. Soon these workers will gain a surplus income and gentrification will happen; plantation workers want cappuccino bars too, why shouldn’t they?

People get angry about what we’re doing at IHA, because they don’t recognise that, however critical they may be on a symbolic level, they exploit plantation labour all the time; their clothes, their food, their shampoo etc. I just draw attention to my art’s inevitable dependency on this labour and build a place where art can think through strategies to renegotiate this. And of course, this will spur the local economy, with plantation workers making serious profits.

So I guess this prize was made for us, for the plantation workers, and for Unilever, too – without their policies in Congo, there would be no need for the institute to engage. Certainly all art engages with society, but not all artists try to take ownership of the role their art plays on society. When Unilever started sponsoring the Unilever Series, Tate Modern became the most visited gallery in the world, branding London as one of the artworld capitals. Unilever – with its headquarters right across the River Thames, could not have made a better investment. My work embraces the inevitability of its own functioning in the world, and so if we start a gentrification programme in Congo maybe, against all odds, a bit of capital accumulation may happen on a Central African Unilever plantation, too.

AR: Making work which reflects society as it is today can involve some of its most difficult aspects. What role do you think art should or could play in better highlighting or understanding these issues?

RM: Art is the one domain where images, forms and ideas can think about themselves. Somehow, if images do that, if they try and understand the structural conditions of their very existence, this understanding also sheds a light on other industries – the division in labour and profit in the production of art is not more or less moral than in the production of cars or shampoo. So all art needs to do is thoroughly understand itself, and then, by extrapolation, it will shed light on the rest of the world, too. And that, of course is exactly what art can do: help the world understand itself.

AR: What has the experience been like to be in a group exhibition such as Artes Mundi? Do you feel particular connections with the other artist’s practices? And what do you think could emerge from this experience?

RM: Oh, it’s been great! Omer Fast and Theaster Gates tasted the chocolate self-portraits – really. The artists are all very strong. We hope we will see these self-portraits in Tate Modern’s museum shop soon, or even on the shelves of major supermarket chains; maybe Sainsbury’s?

AR: Artes Mundi is the largest monetary prize in the UK, offering £40,000 to the winner. Should you win, how do you plan on using the prize money? Do you have a particular project that you would like to use it to realise?

RM: Well, IHA was chased away, our art centre destroyed and drawings confiscated by this Canadian company, Feronia, so plantation workers had huge losses and we’re just trying to start up again. The prize would finance some bamboo studio spaces, with an Artes Mundi’s flag waving over them. And maybe we should hire a security guard, It seems we need one now.

Artes Mundi 6 will be awarded on 22nd January at a ceremony in Cardiff. The prize show is at National Museum Cardiff, Chapter Cardiff, and Ffotogallery, Penarth until 22 February.

22 January 2015.