Painters who communed with the paranormal were often pushed to the fringes – but in recent times, from #witchtok to lockdown hauntings, mainstream culture has taken a decidedly spooky turn

Lately, paranormal researcher John E.L. Tenney has found himself in high demand. Speaking to the New York Times, he reported that twice as many frightened people had contacted him, convinced that an uninvited guest had joined them in lockdown. Their complaints catalogued a full haunted house of ghostly events, from unexplained footsteps, knocks and rattles, to eerie whispers through television sets and text messages from long-dead relatives. The spirit world, we are led to believe, is more active than usual.

What causes these flare-ups of supernatural happenings? The late American artist Susan Hiller thought deeply about this question and spent much of her life making art about esoteric beliefs, from alien abductions to fairy rings and automatic writing. While Hiller was a sceptic – ‘I’m not a believer’, she once definitively confirmed – she insisted that unexplained events should not be dismissed. ‘I’m interested in things that are outside or beneath recognition… I see this as an archaeological investigation, uncovering something to make a different kind of sense of it.’

At London’s Drawing Room, the exhibition Not Without My Ghosts performs the sort of investigation that Hiller might have endorsed. And it begins to reveal why we so often return to the paranormal realm. Squeezed into two and a half rooms are more than 200 years of art by almost 30 artists (including Hiller); the show is an excavation of sorts, uncovering the stories of these artists, many of whom, in their own eras, were pushed to the fringes of the artworld for their esoteric beliefs and practices.

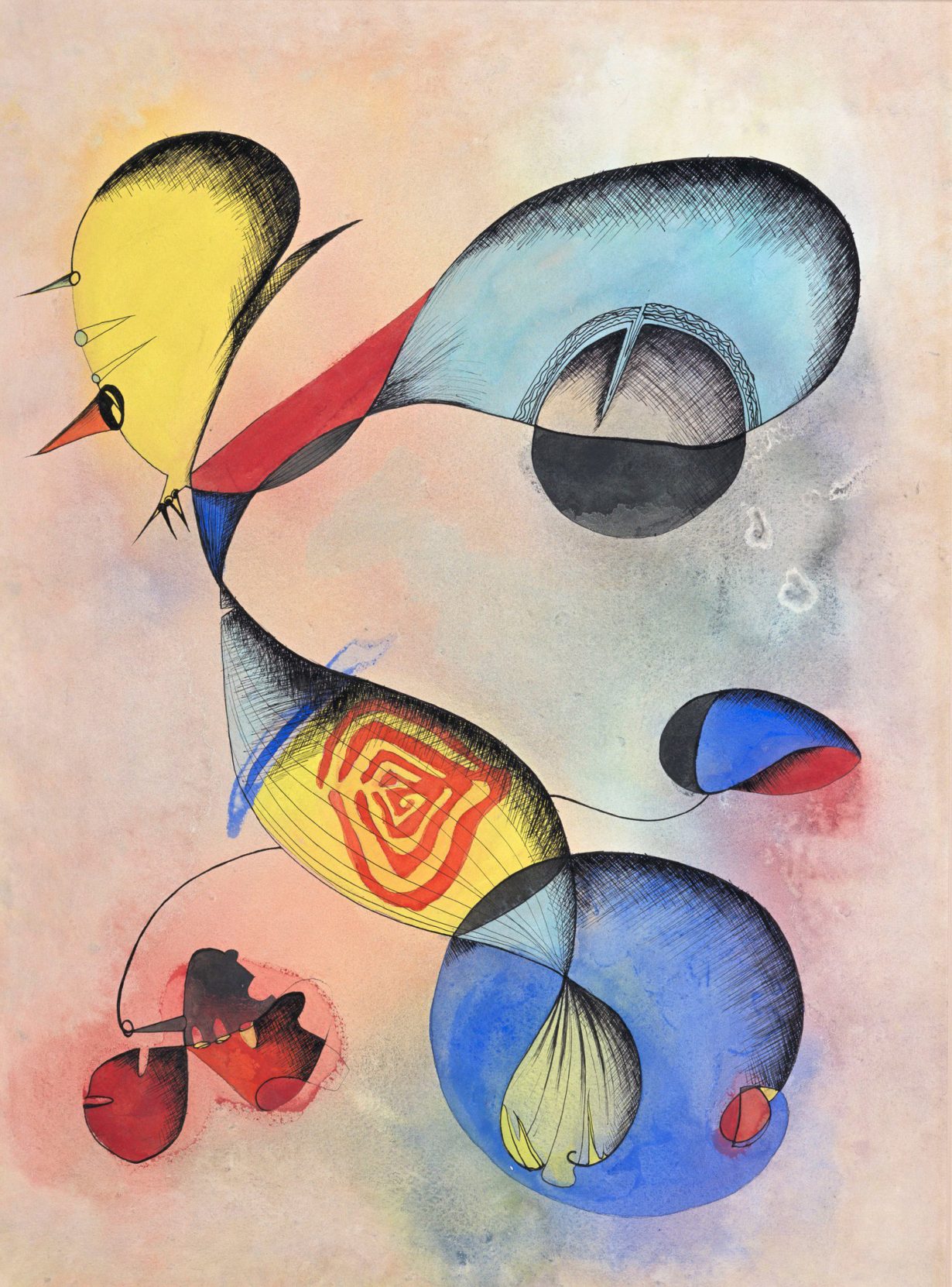

There’s a crisp, primary coloured watercolour by Ithell Colquhoun, for instance, whose refusal to renounce her involvement in various magical societies led to her expulsion from the British Surrealist Group in 1940. Or consider the work of Victorian Spiritualist and Pre-Raphaelite painter Anna Mary Howitt, whose name fell into obscurity after she destroyed her entire oeuvre (her breakdown has been linked to criticism of her work by family friend John Ruskin) and took up spirit art. Both artists were living through eras when the conventional systems of ordering the world were collapsing around them: Howitt’s life saw the publication of Darwin’s theory of evolution and the subsequent crisis of religion; Colquhoun lived through the devastation of two world wars.

Elsewhere on display, there are mediumistic works by William Blake and Victor Hugo, who were both profoundly influenced by their revolutionary eras, as well as visionary watercolours by Marjorie Cameron, who was involved in the countercultural movements of mid-twentieth-century Los Angeles. It is not controversial to suggest that, for these artists, their turn to the paranormal might be understood as a response to the mass social upheavals of their time.

And now, alongside the increase in paranormal activities, the artworld has once again renewed its interest in the occult. In 2018 the Guggenheim’s exhibition of Swedish mystic Hilma Af Klint broke attendance records and Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum brought magical objects together for Spellbound; the following year the Serpentine staged the Swiss healer Emma Kunz’s first UK solo show and Tate acquired Ithell Colquhoun’s archive.

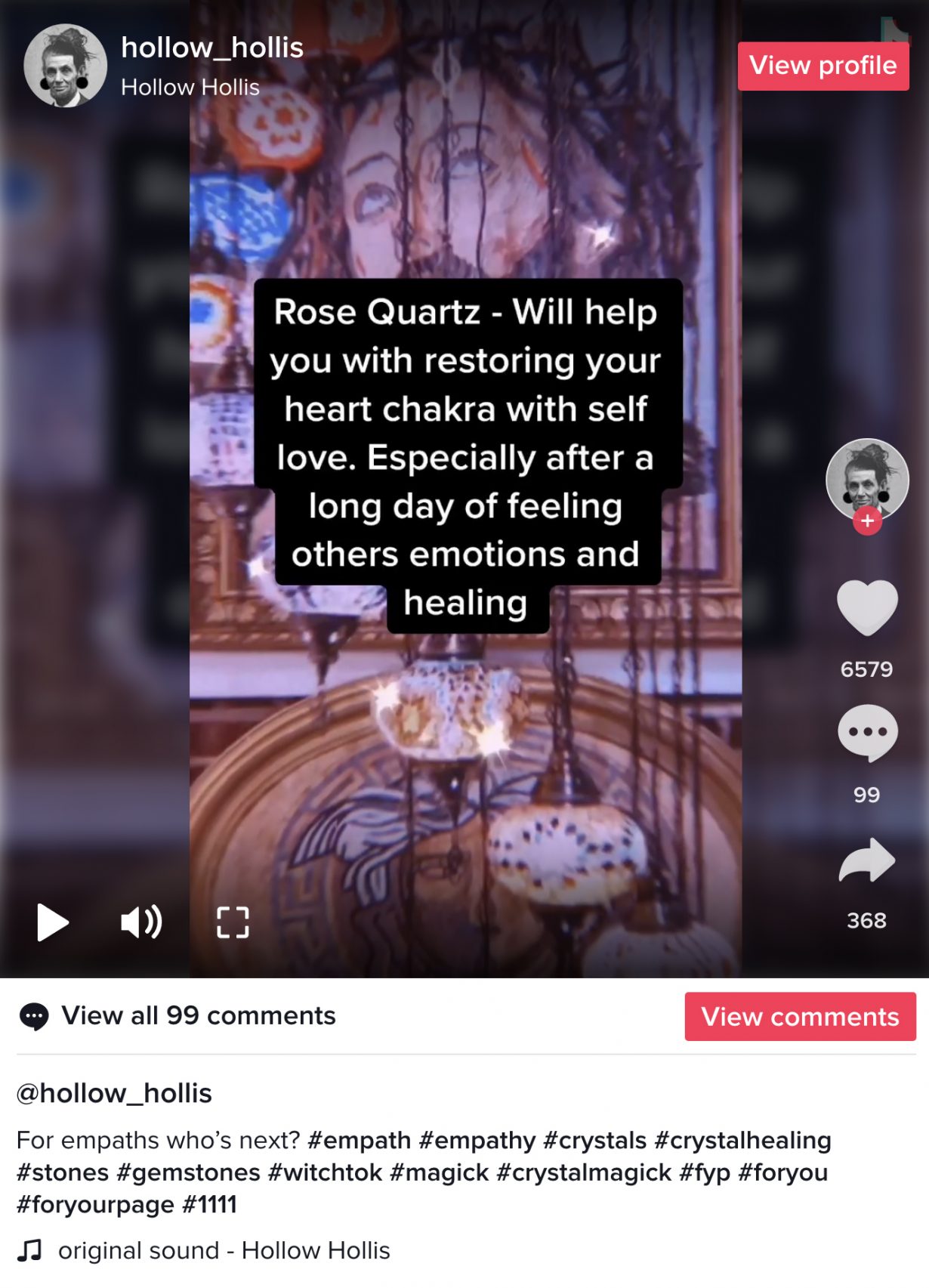

All of these exhibitions sit within the mainstream’s spooky pop-cultural turn. A quick search on TikTok shows that 5 billion people have watched #witchtok videos, and the platform has become the home of a growing Gen-Z coven where self-described witches share telepathy how-tos, informative guides to astral projection and homespun recipes for love potions. In one, a ‘protection spell jar’ tutorial by a Wiccan with 80,000 followers, TikTokers are instructed to fill a glass bottle with sharp objects, sea salt, red string and holy water, before sealing the bottle with candle wax and burying it outside the house. It was inevitable that a generation, burnt by the in-real-life world failing them, would seek to combine self-care with spiritualism. While millennials engaged in (and bought into) mindfulness meditation as a coping strategy, Gen-Z turned to witchcraft.

But it’s important to remember that communing with the beyond means more than self-help; artists have always channelled magic’s radical properties. One of my favourites is poet CAConrad’s project ‘Flying Killer Robots: The Renaming Practice’ (2014), which undoes a spell cast onto our bodies by the US military. After realising the tonal similarities between the sacred sound of ‘OM’ and the term ‘drone’, Conrad invited strangers on the street to chant ‘drone, drone, drone’, feeling ‘the ancient tone quiet [them]’. The word, they realised, has power. ‘Calling them by the name the United States military wants us to use only lulls us into believing they are a viable, safe alternative in warfare,’ Conrad says, and instead invites us to call drones by their ‘right name’: flying killer robots.

In 2020, we have seen our world order melt before us; artists and writers have continued to look to the spiritual to attempt to shape the world in a fairer image. Recent projects have found a surprising guide in the figure of twelfth-century polymath Hildegard von Bingen and her mystical ‘Lingua Ignota’. Artist Adam Chodzko’s Camden Arts Centre digital commission O, you happy roots, branch and mediatrix (2020) interprets the code as a message to the future, developing an algorithm that tracks Hildegard’s constructed language through the natural world. And in Huw Lemmey’s new work of speculative mysticism, the novel Unknown Language (2020) interprets the code as a message to the future, when fragments of Hildegard’s codex wash up on the cracked amethyst planet of Avaaz. In this indecipherable language, perhaps there are the signs of a better future.