From healing through CGI touch to the anniversary of Partition – our editors on shows to see

Priyageetha Dia: Forget Me, Forget Me Not

Yeo Workshop, Singapore, through 16 July

Migrant Indian workers powered many rubber plantations in British Malaya in the early twentieth century. Dia, whose practice often centres on brown identities, histories and bodies, turns to representations of labouring bodies in this show, which contains prints of stock images of Malayan plantations as well as a hammock made out of a latex sheet. The show does not say much about exploitation and trauma, but implies their presence and unknowability. The highlight is a CGI video in which a gilded female protagonist (we.remain.in.multiple.motions_Malaya, 2022) immerses herself among lush trees and blue waters. The many scenes of her silver arm touching stuff – stroking a tiger skin, dipping into waves and caressing the slash marks on rubber-tree trunks – are hypnotic, sensual and oddly healing. Adeline Chia

Nam June Paik: Art in Process

Part one: Gagosian,

555 West 24th Street, New York, through 22 July

Part two: Gagosian,

Park Avenue & 75th Street, New York, 19 July – 26 August

This double-bill survey of Nam June Paik’s four-decade career highlights the Korean-born artist’s enduring interest in changing modes of representation. One of the last works the artist made before his death in 2006 was Lion, a typically absurd sculptural assemblage in which a found wooden Indian sculpture of the big cat stands in front of an arching altar of monitors, each playing looped footage from wildlife documentaries. The filmed animals offer a better likeness to the natural world than the sculpture, and yet Paik plays with that hierarchy by pushing the antiquated cat to the forefront. Oliver Basciano

Jiu-Jiu-Jiu-Yi-Ci”-meaning-Drinking-Once-in-a-Long-Time-1230x820.jpg)

Unaccounted Travelogue

Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei, through 31 July

The literal translation of the Chinese title of this exhibition, feiyuji, is ‘anti-travelogue’, and it is an unflinching yet life-affirming look at marginalised groups in Taiwan and Thailand who basically do not travel for leisure. The show is divided into two sections. ‘Not Here For Fun’ centres on Thai migrant labourers who work in Taiwan, and features their writings and artworks, and information about their cultural and reading spaces. The second part, ‘True Love Can Wait Forever’, draws connections between molam, a folk music genre in the Isaan region in northeast Thailand, and linban, songs sung by indigenous forest workers in Taiwan. Adeline Chia

Samira Rathod: Dismantling Building – A Kit of Parts

Chemould Prescott Road, Delhi, through 2 August

If I tell you that one of architect Samira Rathod’s latest projects is called ‘the House of Concrete Experiments’ and that it’s a sculptural dwelling whose walls incorporate waste (large and small) gathered from the site, whose ceilings incorporate B-shaped lightwells, whose entrances feature cantilevered concrete slabs for shade and whose structure is fragmented in order to avoid removing any of the mango trees onsite, you’ll begin to understand why it makes sense to show her work in an art gallery. Although it also helps that the architect and furniture designer’s firm, Samira Rathod Design Atelier (SRDA), recently renovated the ancestral home of Chemould Prescott Road’s artistic director. It’s a new series of furniture that’s on show, largely made of local wood (teak, rosewood, AIN, jackfruit and Kendal) with the help of local karigars, the resultant desks and tables look in part like architectural plans or models, in part, thanks to the deployment of piston-like forms, like steampunk assemblages, while nevertheless retaining the material trace of the geographic context from which they come. Apparently you can use them too. But they seem altogether too distracting to allow you to focus on anything else. Nirmala Devi

Catherine Opie: To Your Shore From My Shore And Back Again

Lehmann Maupin, Seoul, through 20 August

In 2009 Catherine Opie boarded a cargo ship that set sail from Seoul to the artist’s native USA. Best known for her portraits of queer friends and performers, the veteran photographer had very few people around her for these ten days: just the crew, plus stacks of shipping containers. It was beyond the boat that she trained her lens however, making a series of meditative, melancholy images of the sea’s horizon at sunrise and sunset. While her better-known work blurred gender and identity boundaries, here it is time and national borders caught in flux. Oliver Basciano

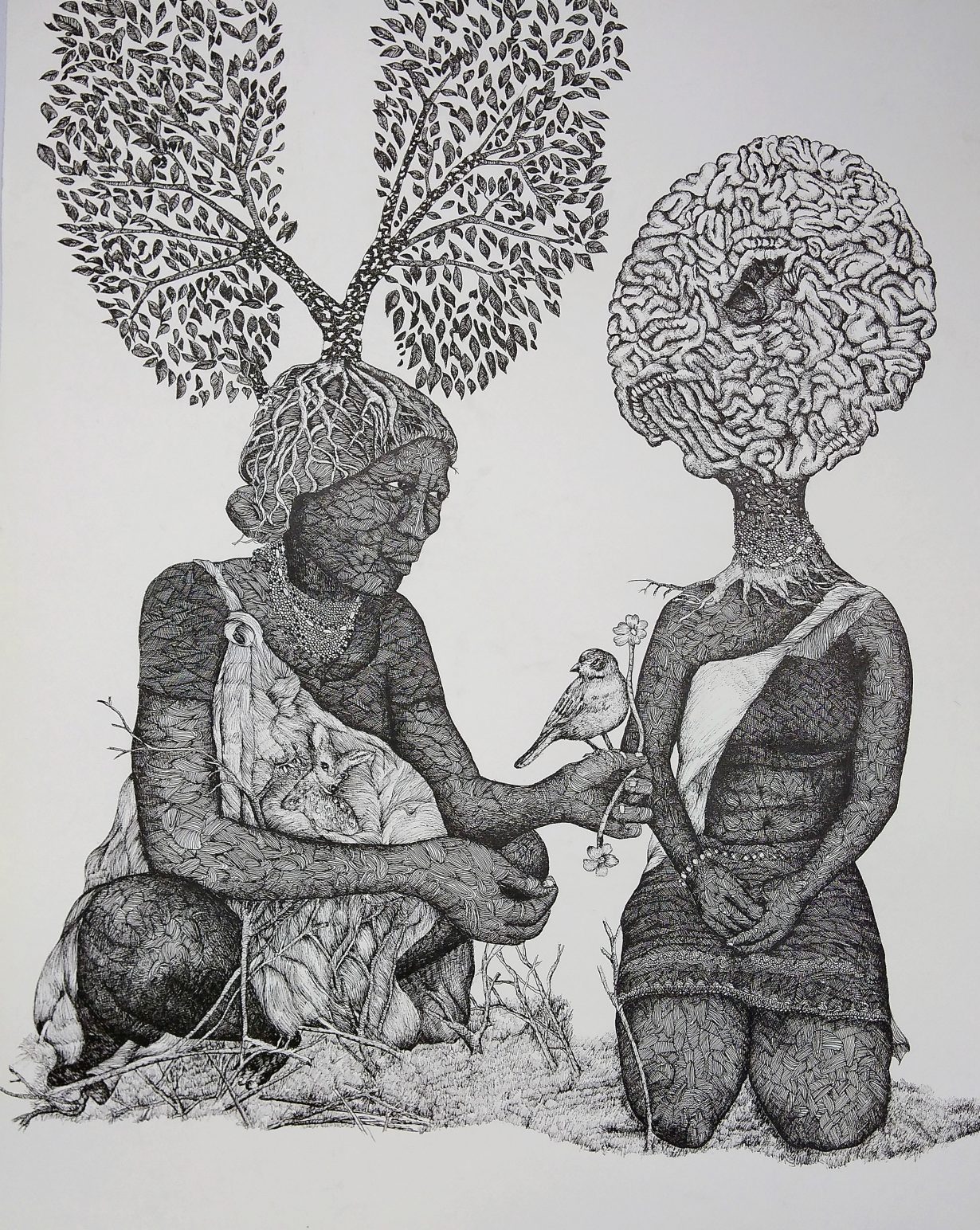

Joydeb Roaja: Roots

Jhaveri Contemporary, Mumbai, 14 July – 20 August

An indigenous artist from the Chittagong hill tract area of Bangladesh, Joydeb Roaja works primarily in performance, installation and drawing, often finding inspiration and materials among the area’s tribal cultures and natural hilly landscape. This exhibition of intricately drawn ink-on-paper works revolves around the entangled relationships between nature and Joydeb Roaja’s indigenous community. Human bodies blend seamlessly into branches, leaves and roots to create visions of interconnectedness and resilience. Adeline Chia

The Immeasurable and World’s End

JWD Art Space, Bangkok, through 28 August

One of a handful of Thai artists already confirmed for the upcoming Bangkok Art Biennale, Chitti Kasemkitvatana was, for a spell during the late 1990s, on a similar career trajectory as Rirkrit Tiravanija, with whom he co-edited the short-lived VER magazine (the precursor to Bangkok’s Gallery VER). That is, until he withdrew by becoming a Buddhist monk for most of the 2000s. Since 2011, however, he has sporadically returned to art and – as is the case with The Immeasurable and World’s End at JWD Art Space – curating. Grounded in his interest in the subjectivity of time and memory, and how different spacetime concepts influence social structures, this exhibition of works by 14 artists from Australia, India, Lithuania, South Korea and Thailand is cut from the same minimal and conceptual cloth that marked out his early curatorial forays at Bangkok’s seminal About Café. Through a smorgasbord of practices – from Varsha Nair’s diaristic memory maps drawn on palm leaves to Henry Tan and partners’ mycelium lab exploring lunar biology and terraforming – Kasemkitvatana offers us

a domain of encounter, a loosely networked free space as porous and fluid as his unusual biography. Max Crosbie-Jones

Pichet Klunchun Dance Company: Evolution

Noble Play, Bangkok, through 28 August

For over two decades now, Pichet Klunchun and his troupe have been contemporising classical Thai dance – especially khon, an angular and refined masked dance form traditionally performed at the royal court – through an approach that is at once reverent and impudent. Evolution at Bangkok’s Noble Play showroom is being punctuated by weekly performances of key works (including kinetic solo pieces Phya Chattan and I am a Demon), giving it the feel of a kaleidoscopic career retrospective; but its exhibition element is also breaking new ground by charting his wont for deconstructing and developing dance traditions through a cross-disciplinary series of installations. Among them is a display of black-and-white photos capturing the poses and movement of Nijinsky Siam, which is Klunchun’s choreographed response to the archival photographs of early-twentieth-century ballet legend Vaslav Nijinsky performing Michel Fokine’s Thai classical dance- inspired work, Danse Siamoise (1910). Also on display are pencil drawings of the 59 ‘Thepphanom’ moves that become, through rote-learning, second nature to classical Thai dancers, while both the immersive VR room and the industrial robot-arm carving new iterations of traditional khon masks gesture broadly towards the mutating and future-orientated dance language of one of Thailand’s foremost iconoclasts. Max Crosbie-Jones

Hito Steyerl: A Sea of Data

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, through 18 September

Bringing together 23 representative works from the influential Berlin-based artist-filmmaker-theorist, this survey exhibition is a good chance to sample the breadth of her practice. Featured works range from early pseudo-documentary projects such as Germany and Identity (1994) to her latest MMCA-commissioned installation, Animal Spirits (2022). The latter, a four-channel video-work, centres on a mockumentary about a reality TV show trying to infiltrate a small mountain village in Spain and morphs into a critique of the wild capitalist markets in bitcoin and NFTs. Adeline Chia

Checkpoint: Border Views from Korea

Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, through 18 September

Borders are always lines of political tension, in some places more than others. For the people of North and South Korea, the division of the Korean peninsula after the Second World War has meant, since 1953, the presence of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), a strip of land separating the two (technically still-at-war) countries, with the North an isolated and mysterious world, even if only kilometres away from the South. Checkpoint: Border Views from Korea presents work by 20 artists – including Lee Bul, Haegue Yang, Chan Sook Choi and Adrián Villar Rojas – exploring the fractured history and present of the two states, opposing products of the Cold War. Since North Korean artists are (inevitably) absent, the show offers multiple reflections on separation and the persistence of human connection and cultural ties, even as states stubbornly face off, over years and decades. J. J. Charlesworth

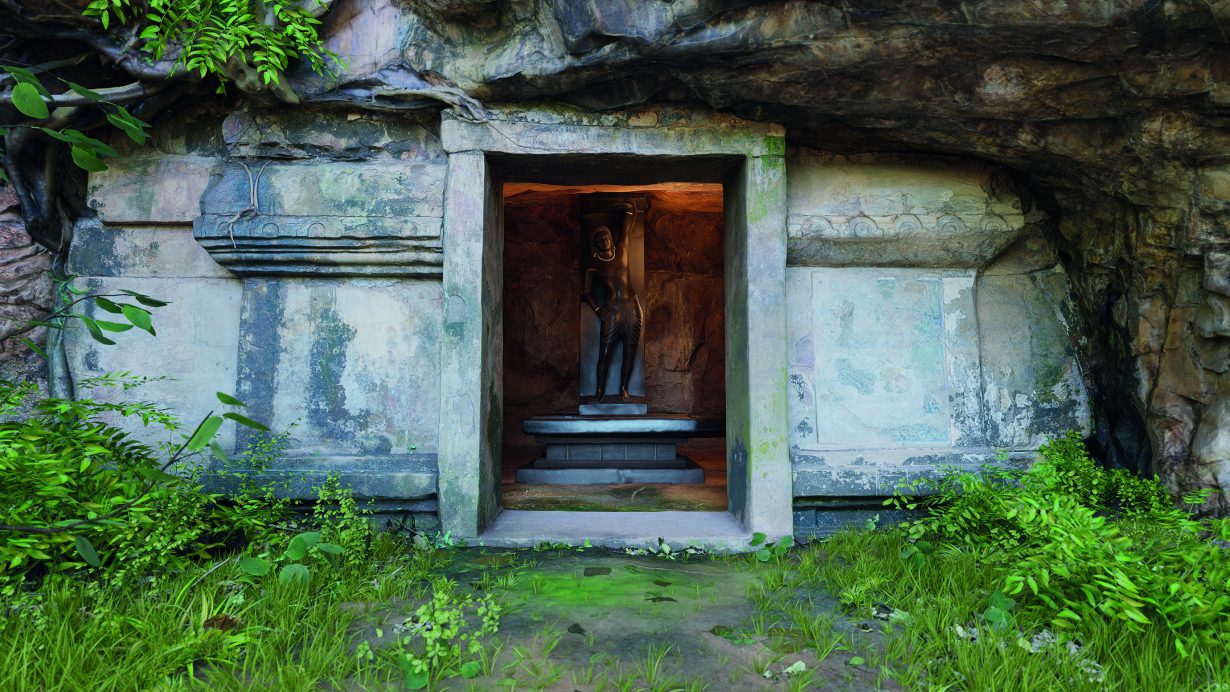

Revealing Krishna: Journey to Cambodia’s Sacred Mountain

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Washington, DC, through 18 September

According to Tess Davies – the cultural racketeering specialist behind key research into the illicit trade in Cambodian antiquities, including the late Douglas Latchford’s smuggling ring – Western museums should be viewing repatriation as an opportunity, not an obstacle. That sentiment clearly informs Revealing Krishna, which after debuting at Ohio’s Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) has now moved to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art. Featuring digital projections, augmented-reality headsets and a documentary, the exhibition is a collaboration with Cambodia’s National Museum centred around a larger-than-life statue of Hindu god Krishna holding up a mountain. Standing close to two metres tall, the one-ton Khmer sculpture – thought to have been removed from the manmade caves of Phnom Da, a mountain in southern Cambodia, in the early twentieth century – was restored during the late 1970s, shortly after the CMA acquired it. But the recent back-and-forth exchange of fragments with the National Museum in Phnom Penh, coupled with modern scanning techniques, has conclusively proven those changes incorrect. While the exhibition chronicles the life story of this newly restored masterpiece – including the mystery of its successfully reattached left hand and its dramatic (if only temporary) reunion with some of the other stone gods of Phnom Da – it also exemplifies the constructive relationships and new loans that can result when a major museum chooses to build bridges rather than defensive walls. Max Crosbie-Jones

Aichi Triennale: STILL ALIVE

Various venues, Aichi, through 10 October

Still Alive. That is the pandemic-apt theme of this year’s Aichi Triennale and a nod to Aichi-born On Kawara’s famous series of telegrams sent to acquaintances around the world announcing ‘I AM STILL ALIVE’. Curated by Mami Kataoka, the exhibition explores the meaning and obligations of survival to build a more equitable and sustainable world. The 82 participating artists include On, Kader Attia, Anne Imhof, Shiota Chiharu, Hsu Chia-Wei and Mit Jai Inn. There will also be a performance art programme featuring artist and filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul presenting his first VR work. Adeline Chia

Melati Suryodarmo: I am a Ghost in My Own House

Bonnefanten Museum, Maastricht, through 30 October

Suryodarmo’s physically demanding, apparently absurdist performance works address how human physical presence and action might be distilled into meaning for its audience. Drawing from Japanese Butoh as well as on the history of Western performance art (she studied for a time with Marina Abramović) Suryodarmo’s works have previously involved such fraught scenarios as firing 800 arrows into the walls of a gallery over four hours, or handling a large, awkward, heavy sheet of glass while repeating “I love you” for even longer. Suryodarmo’s work has won her this year’s €25,000 Bonnefanten Award for Contemporary Art, and this solo exhibition presents documents, artworks and video recordings from over two decades of this Indonesian artist’s minimal but intense oeuvre. J. J. Charlesworth

Pritika Chowdhry: Unbearable Memories, Unspeakable Histories

South Asia Institute, Chicago, through December 2022

India’s independence from British rule in 1947 brought with it the chaos and suffering of Partition into what would become modern-day India and Pakistan. Two million people died in political violence and over twenty million were displaced. With Partition’s 60th anniversary, in 2007, Chowdhry began her Partition Anti-Memorial Project, a series of sculptural and installation works that each bring attention the forgotten, often bitter and enduring consequences of Partition on Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi society. At South Asia Institute, Chowdhry’s 15-year project is revisited to mark Partition’s 75 years, asking the question, ‘When a memory is unbearable, how does one memorialize it?’ J. J. Charlesworth

Indigo Waves and Other Stories: Re-Navigating the Afrasian Sea and Notions of Diaspora

Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town, through 29 January 2023

In Sohrab Hura’s 17-minute film The Coast (2020) we see the locals of a beach-side village in southern India playing in the waves at night. Somewhere in the darkness, 2,000km across the water, is the easternmost tip of Africa; 5,000km in the other direction is Australia. The huge expanse of water between – variously known as the Indian Ocean, the Swahili Sea, Ziwa Kuu or Bahari Hindi – is the subject of this exhibition of 13 artists. Among those joining Hura are Taiwanese artist Cetus Chin-Yun Kuo, whose work deals with the social and political consequences of cartography; Australian Isha Ram Das, whose soundworks stem from ecological concern; and figurative painter Cinga Samson, a local to Cape Town. Oliver Basciano