Just as NFTs try to reinvent an artwork’s aura, the audio app thrives in its promise of exclusivity

The appeal of audio media is obvious: when work or some other activity takes away your eyes but leaves your ears (and the space between them) relatively unoccupied, audio helps pass the time until you can pay full attention to what you want to again. As long as the audio content is available on demand, it can be deployed to fill the empty, distracted moments of perpetual COVID-19 lockdowns. Podcasts have come to exemplify this. While their informational density may vary widely, they all tend to convey a parasocial vibe of leisurely hanging out. You get the unpressured ambience of humans enjoying one another’s company (plus ads).

It may seem as though Clubhouse – the new platform that organizes and streams live conversations to your phone, beloved by the Silicon Valley elite and artworld VIPs alike – would do something similar, quieting the voice in your preoccupied head with the engaging sound of other voices. But audio doesn’t need to be live to perform that function. Why then has Clubhouse thrived by turning podcasts back into broadcast radio?

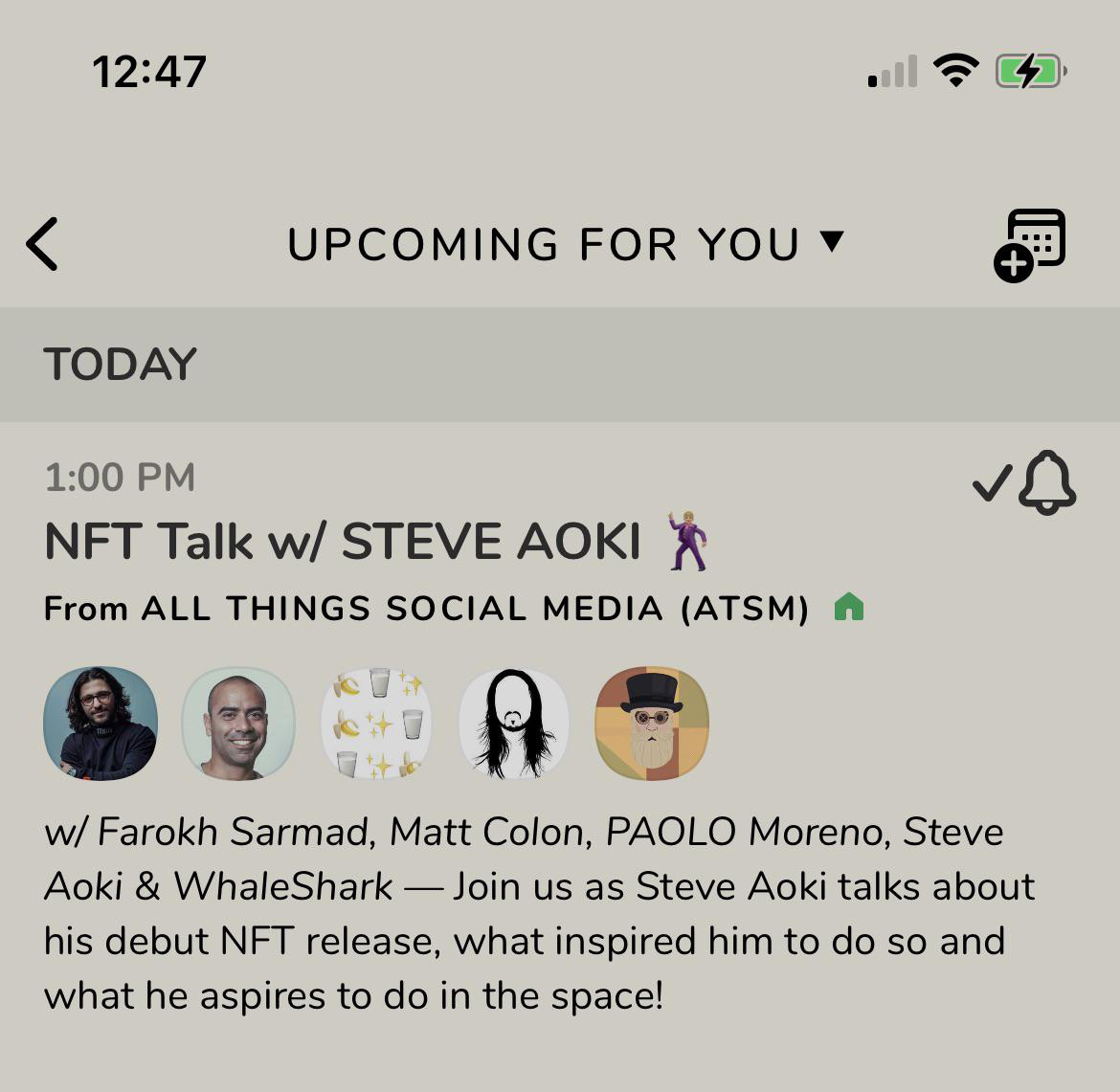

For the short term, at least, part of what Clubhouse offers – as its name suggests – is the promise of exclusivity: new users currently must be invited by current users, and who invited you becomes a permanent aspect of your profile on the (iOS-only) app, a letter of reference of sorts that suggests broader accountability (who let this creep in here?) while also announcing a user’s clout. Limiting access has also been a well-tested means of creating hype around a tech product, reinforcing the ersatz prestige that’s supposed to come with being an early adopter. Clubhouse has been conspicuously populated with ‘thought-leader’ types – from Elon Musk and Kanye West through to endless artworld roundtables on NFTs – eager to espouse visionary thoughts without fear of critical scrutiny. (The platform prohibits users from recording or transcribing conversations without permission.)

But early adoption is also important to another phenomenon that seems highly Clubhouse-adjacent: pyramid schemes. In a recent essay about Clubhouse for the New Yorker, Anna Weiner notes that ‘while there are people using the app in imaginative, social, and subversive ways, something about its overall tone seems predetermined – a natural outgrowth of the ‘creator economy’ […] It is hard to shake the feeling that everyone on Clubhouse is selling something: a company, a workshop, a show, a book, a brand.’ Financial Times editor Izabella Kaminska pointed out on Twitter that one ‘obvious use case for ClubHouse is propagation of MLM [multilevel marketing] schemes. In the 80s we used to be invited into rented rooms in shabby 4 star hotels to hear our ‘business opportunities’. Now it’s NFTs in CH.’ The same exclusivity that makes venture capitalists and tech executives comfortable speaking out also makes Clubhouse an ideal spot to isolate prospective marks and pressure them out of any sense of due diligence. Perhaps a more accurate name for the app would be Timeshare.

The real-time nature of Clubhouse is well-suited to creating the ‘act now’ urgency of the hard sell. The idea that one is getting the information live – as when one obsessively consumes financial news – is crucial to the fantasy that you can know something that maybe someone else doesn’t, that you can fall into a singular opportunity by being at the right place at the right time, by having special access. What Clubhouse promises is not just information or distraction but that sense of timeliness: moments that can’t be duplicated without creating some distance from the original, ‘real’ moment, just as NFTs try to reinvent an exclusive aura for works that are intrinsically duplicable.

In relation to the promiscuous dissemination of words and images, to the endless feeds and recurrences in digital culture, Clubhouse wants to ground value in cloistered conversations rendered artificially unrepeatable. But these are not valuable in themselves, in how they supposedly sanctify an ephemeral moment of true presence or put you ‘in the moment.’ The value of presence is only realised by being fused to sales pitches, as though what is genuine can only be what is marketable. Anything that can be understood as ‘authentic’ must already be memorabilia. For moments to feel real, they must close a deal. Clubhouse takes the metaphysics of presence that Jacques Derrida critiqued – the idea that writing is derivative and speech is more authentic – and builds a business model out of it. If you’re reading this, you’re too late. The NFT auction has already taken off.