The artist’s memoir reconciles his experiences with an examination of alternate definitions of ‘home’

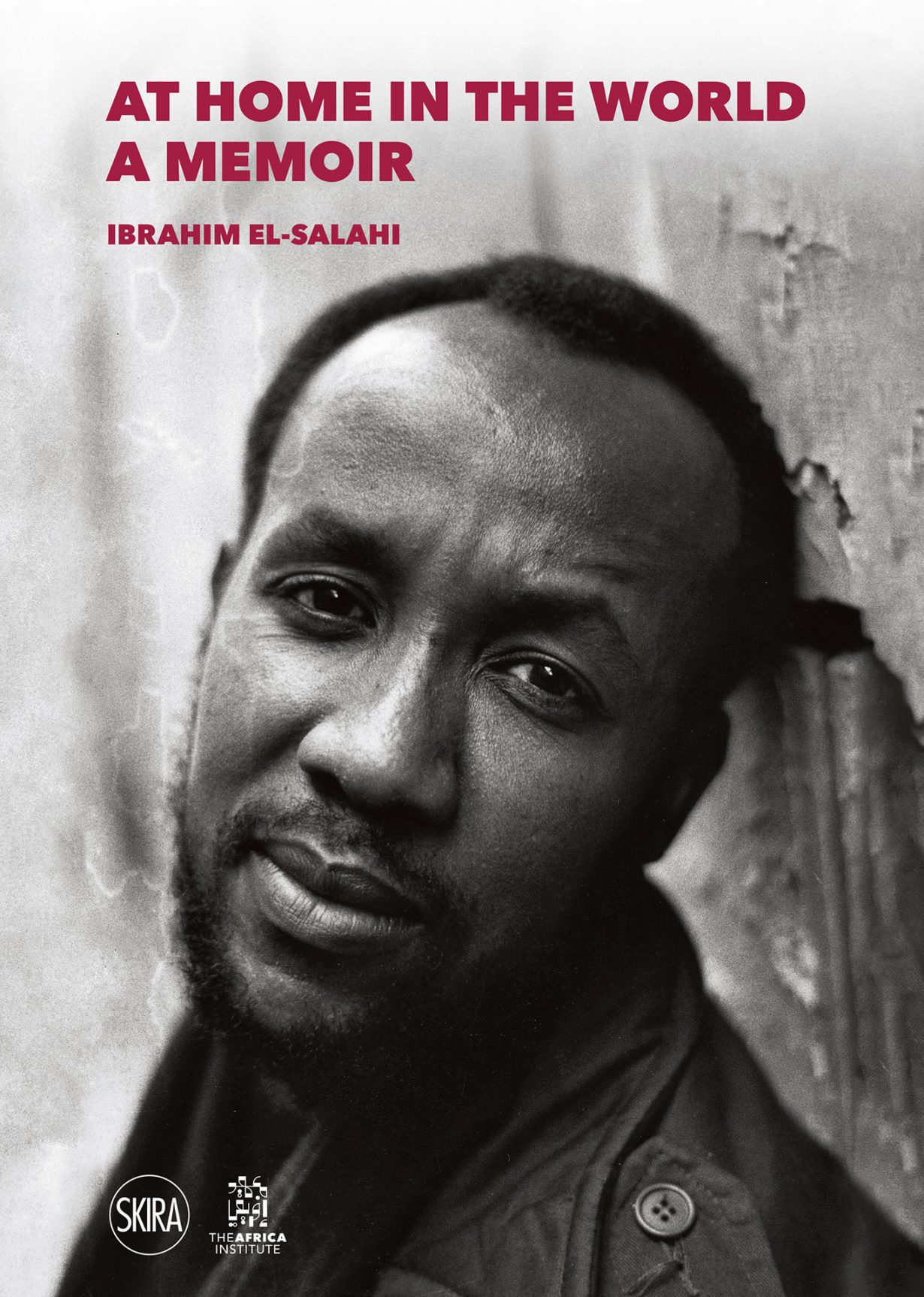

Before he was widely celebrated as one of the pioneers of African Modernism, Ibrahim El-Salahi lived a life that featured unemployment, imprisonment, various instances of straightforward racism, lengthy periods of not really showing his work and a long exile from his native Sudan. So you’d be forgiven for feeling that the now-nonagenarian painter has a rather curious idea of what being ‘at home’ means. And all the more so given that his artistic influences – and the philosophies he developed out of them – blend Arabic, African, European and North and South American traditions in a way that doesn’t find a home, in terms of standard art-historical mapping, in any of them. Naturally, then, this memoir is one that turns on the examination of alternate definitions of ‘home’.

It begins with a detailed description of the author’s (extant) childhood home in Omdurman, one of three towns that make up Khartoum. From there El-Salahi traces his education, both religious (his father ran a Qu’ranic school) and secular; his rebellions against the unjustly wielded authority of his teachers (hurling a stone at the forehead of a schoolmaster who was preparing to whip him); and the more general impact of a colonial education. This last meant lessons exclusively in English during secondary school, where ‘every effort was taken to make us feel that we were distinctly different from the rest of our folks… the future effendis of a new Sudan under British rule’. As El-Salahi proceeds to tell it, the patterns established in his youth would go on to repeat through the rest of his life.

For now the future effendi turned to studying art, first in Khartoum, then moving to London to study at the Slade on a government scholarship between 1954 and 1957. During that time Sudan became independent and the artist married his first wife, an Englishwoman, and fathered his first child.

Despite his encountering England’s endemic racist attitudes, El-Salahi’s time in London is productive. In addition to his artistic endeavours he becomes involved in student organisation, being elected secretary of the Sudanese Students’ Union. In that capacity he organises a visit to the Third International Youth Festival in Warsaw, in 1955 – despite attempts by the Sudanese government to discourage him – after which, having left behind the work he took to show there, he boards the wrong train and ends up in East Berlin, where he spends his first, albeit brief, period of incarceration.

And yet despite his evident enjoyment (prison aside) of this exposure to an international artworld, the artist struggles to reconcile his experiences abroad with the realities of home when he returns to Sudan (to teach art). Much of El-Salahi’s early study had involved trips to heritage sites in his homeland and in Egypt – learning about the land in addition to his formal education. Now he becomes acutely aware that the easel painting in which he has trained is not part of the artistic traditions of the Nile Valley. And is consequently something that might not resonate with the people of a newly independent postcolonial nation. ‘I personally felt that a bridge had to be built to close the gap between the two parties,’ he declares. And then sets out to travel around Sudan to find out what people actually hang on their walls.

What he discovers are two elements that were familiar from his own childhood home: Arabic calligraphy, and African motifs and decoration. All of which leads him to think about art as a triangular relationship: ‘me’ (the message of the artist and the satisfaction of the creative process), ‘others’ (the society and culture from which one has borrowed) and ‘all’ (humanity and society at large). While this research directs El-Salahi, on the one hand, to experiment with calligraphic and decorative motifs – and to his part in the founding of what became known as the School of Khartoum – on the other it becomes a formula by which he lives his artistic life.

On UNESCO-funded research trips to the US, he is just as interested in the opinions of ordinary people (taxi drivers, soldiers about to enlist to fight in Vietnam) as he is in the aesthetic development of fellow artists (African-American modernists such as Jacob Lawrence), religious and civil rights leaders (such as the Nation of Islam’s Elijah Muhammad, whom he visits at home in Chicago), and sports stars such as Muhammad Ali (while impressed by his embrace of Islam, El-Salahi struggles to get over the boxer’s ‘enormous’ fists). When he meets sculptor Richard Hunt in Chicago – just after having reported that, during the mid-1960s, the city shrugged its shoulders and went back to normal after the 10,000 people summoned by Martin Luther King during his Freedom Campaign marched to City Hall – they discuss ‘how people in Africa felt about African Americans who wanted to belong and to revive their African roots, going to the extent of wearing robes, imagining that they were African in origin in contrast to the others who wanted to be recognized as Americans’. At the same time, El-Salahi makes efforts to experience how indigenous arts are preserved, visiting, for example, the Museum of Navajo Ceremonial Arts in New Mexico, where an encounter with Navajo sand paintings coincides with his ideas for the preservation of dying crafts in Sudan.

Indeed, his curiosity about and engagement with cross-continental dialogue is relentless: there are further research trips to China, São Paulo and Mexico, all seeking insights that might inform the development of modern art in Sudan and create alliances and solidarities on a global level, many of them dedicated to fights against tyranny in whatever form it takes. That being said, in this narrative El-Salahi steps back from any overt analysis of the political messages inherent in his own work.

Back in Sudan, El-Salahi graduates from teaching art to increasingly bureaucratic governmental work: after a spell as a cultural attaché back in London, he is eventually appointed Undersecretary in the Ministry of Culture and Information in 1975. Soon after this, he is suddenly – and without trial – imprisoned for allegedly participating in an antigovernment coup. His incarceration lasts six months and eight days, during which time he isn’t allowed to write or draw. Nevertheless, he finds a way, drawing on fragments of food bags that he buries daily in the prison yard (never to be retrieved). Upon his release, this generates in turn a new way of working, by creating wholes from fragments. Having been reinstated in his former job as though nothing had happened, he nevertheless goes into self-exile in 1978 to work for the government of Qatar, until his activities there are curtailed by a sudden regime change. He now lives in Oxford, fully focused on his art. Yet on the basis of this engaging, acute and at times almost incredible account, it might be more accurate to say that little bits of him live everywhere, or that little bits of everywhere live in him.

At Home in the World: A Memoir by Ibrahim El-Salahi Skira Editore, £35 (hardcover)