At Luxembourg & Co, London, Balthus’s objectifying voyeurism reminds us of the dubious, sometimes obscene power of images

The eccentric Swiss painter Balthus (1908–2001) has long generated controversy, mostly for his paintings of young girls and women found in disconcerting, dreamlike interiors, awkwardly posed, often reclining, seemingly asleep, bare legs exposed below suggestively short skirts. In recent years, museum exhibitions of his works have occasioned protests and petitions against their charged and vaguely suspect eroticism, embodied by his perhaps best-known canvas Thérèse Dreaming (1938).

That contemporary notoriety inevitably sticks to this show of nine paintings and five drawings, all but one of which are of female subjects. Making sense of what produces the disquiet in these paintings isn’t so straightforward. Two pencil-on-paper studies of naked young women (Étude pour ‘Le Lever’, 1974, and Nu debout, 1969–70) are unambiguous in focusing on their subjects’ genitals. They’re mounted – coyly, as if to prevent any possible offense – on the reverse of wall-mounted rotatable picture-frames, the fronts of which present two other innocuous, even tritely sentimental, pencil portraits of young women sleeping (Nu endormi, 1969–70, and Katia Endormie, 1969–70).

However, the repeating fixation on dreaming women, partly unclothed but never revealing anything, only properly comes together in Balthus’s paintings, testaments to a kind of paralysed and frigid voyeurism. The show is dominated by three large canvases, each rehearsing differing compositions of three young women arranged around a central sofa. In each, the central girl has one leg hitched up on the sofa, looking imperiously out of the canvas, while in one (Étude pour ‘Le Salon’, 1941) her companion crawls on the floor, or in another (Les trois soeurs (Sylvia, Marie-Pierre et Beatrice Colle), 1954–55) is hunched on the ground like a monkey, scowling at the viewer while gnawing at an apple, while a third sister, sat bare-shouldered in a bandeau dress, quietly ignores the scene as she reads a book in her lap.

These toylike figures are echoed by the stick-thin woman in tiny pointed shoes who stands like a porcelain doll in Portrait de Madame Pierre Loeb (1934). Passivity and inertia weigh on these paintings, which hints at what organises Balthus’s psychological universe – the turning of everything alive and sensuous into a kind of dead object. Even the neoclassical landscape of Paysage de Champrovent (1941–45), with its lush valley and rolling green mountains, has its own ambiguous voyeur built in – a woman reclines on the grassy foreground, head propped on an elbow, her short dress clinging thinly to her hips. The logic of the image is genuinely perverse: she’s both a displaced repetition of the landscape she admires, and a willing subordinate to it. As viewers we’re then implicated in this bizarre tryst, between a passive ‘feminine’ symbol and her all surrounding geological suitor, standing in for the artist, hiding in plain sight.

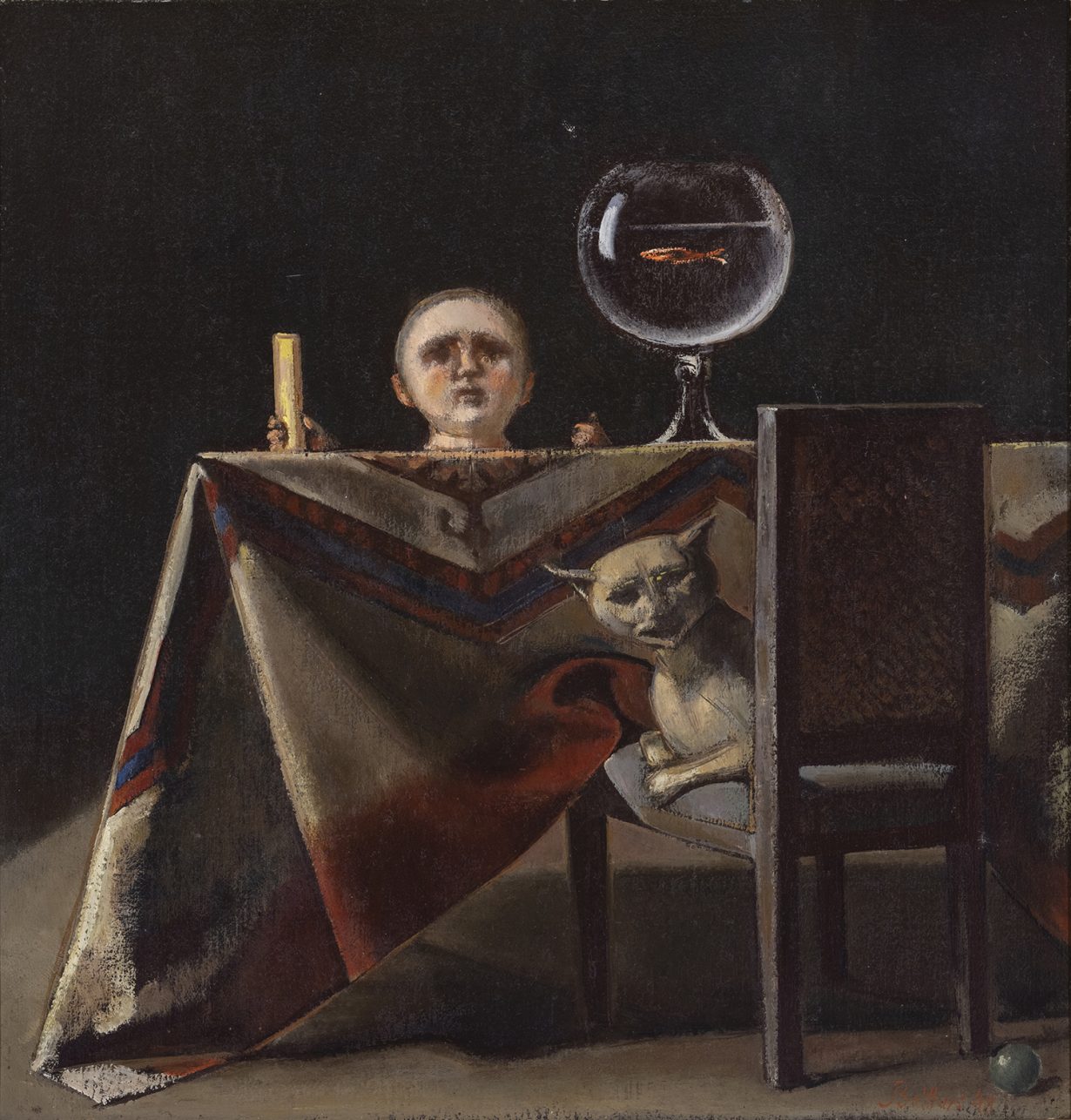

Balthus’s depressive, prurient weirdness casts everything as passive and de-energised, even to the point of suggesting the perspective of a viewer in a state of psychological disintegration. The most disturbing image here isn’t of an idealised female, but of a child. Le poisson rouge (1948) has the titular goldfish in a bowl on a draped table, starkly lit against a black background. Above the line of the table is the round head of a child, a hand to one side of him holding a candle. But the drapery is hitched up to reveal that there are no feet or legs to support this boy, so that his head now looks like an effigy, placed on the table. In front of this is a chair from which a devilish catlike animal grins malevolently back at us. Objectification is a state Balthus seems to revel in, and it’s never really clear whether these paintings ever transcend this pathological sense of a narcissistic sensibility willing itself into lifelessness. Nevertheless, that these paintings succeed in letting us in on this lonely, arrested worldview makes them worth seeing, as a reminder of the dubious, sometimes obscene power of images.

Under the Surface at Luxembourg & Co, London through 4 June