The 2022-23 edition, Chaos: Calm, hopes to reflect ‘the zeitgeist of the confusing world we live in’ – and so there’s Google Earth, shattered chandeliers and Guns N’ Roses lyrics

Yee I-Lann’s single-channel video Pangkis (2021) features echoing screams, chants and seven dancing barechested men wearing woven hats conjoined by a series of branchlike tubes. Needless to say, they dance in sync. Indeed, given that they’re also barefoot and wearing black jeans, you might easily mistake them for a boy band. Except for that hat (a sculpture in its own right, titled 7-headed Lalandau Hat, 2020), which is based on the traditional ceremonial headdresses worn by men of the Murut ethnic group (mainly found in the artist’s home state of Sabah, in Borneo). And the fact that the men are performing a take on a traditional warriors’ dance. It’s a clash of tradition and modernity, and the particular and the general, that’s echoed by the two works hung either side of the long white mat in front of the video on which the audience is invited to sit – one (hello from the outside, 2019) a woven bamboo mat bearing the full lyrics to Guns N’ Roses’s Sweet Child O’ Mine (1988), the other a mat with the lyrics to a popular Thai song (rendered in Thai): น้ำก็นองเต็มตลิ่ง (Water floods the riverbank, 2022). The weavers of such mats are primarily female and they present a different aspect of community – simultaneously quiet and loud – to accompany that offered by the prancing, shouting men who have been physically ‘tied’ together. Located in the Sermon Hall of Wat Prayoon, a nineteenth-century temple complex in the Kudeejeen district of Bangkok that is, appropriately, another form of community centre, the work functions as a world inside a world, carefully choreographed and subtly immersive. The nearby stupa houses the Buddha’s relics; and for all the screams, Yee’s display as a whole also offers a kind of serene calm. A kind of sacred karaoke hall.

For the most part, however, the third edition of the Bangkok Art Biennale is more a reflection of chaos than calm, spread across 11 venues (and one virtual space) and featuring the input of a five-strong curatorial team (founding director Apinan Poshyananda and curators Nigel Hurst, Loredana Pazzini-Paracciani, Jirat Ratthawongjirakul and Chomwan Weeraworawit) and the works of 73 artists, which often collide with each other rather than conversing side by side. Though a generous person might say this is a true reflection of our times. Or as the exhibition text puts it, a reflection of ‘the zeitgeist of the confusing world we live in’. Which isn’t, let’s face it, much to go on.

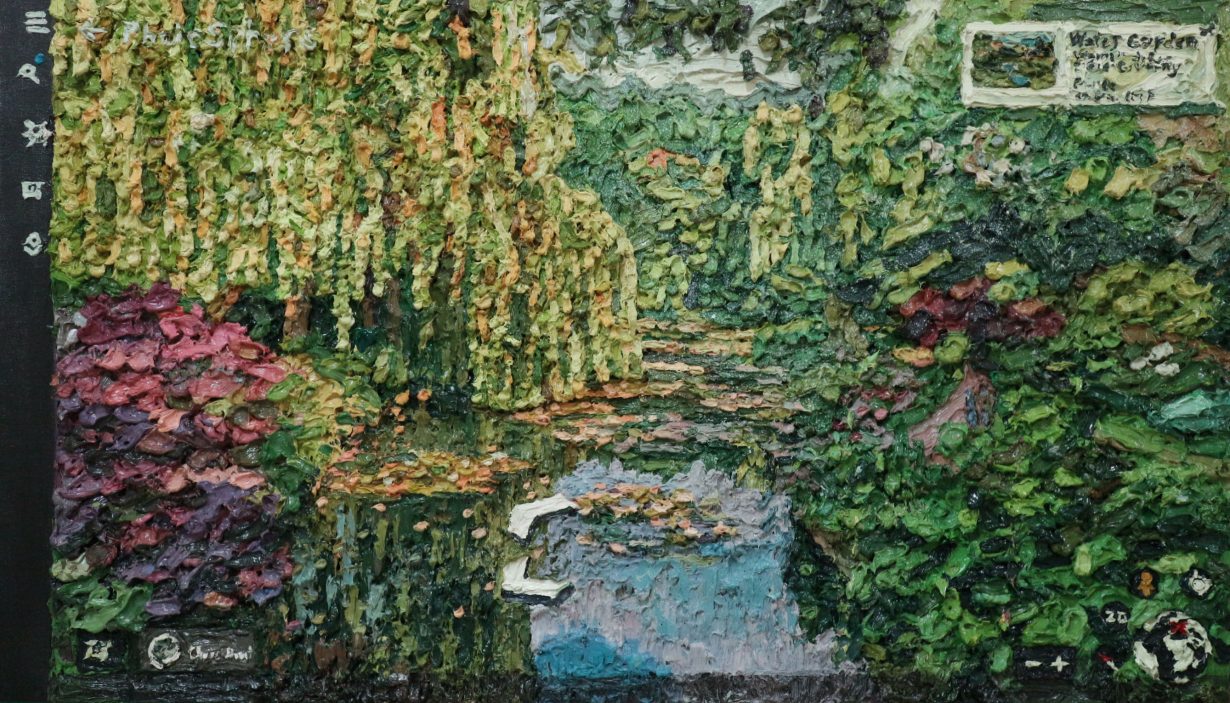

Epitomising this is the overstuffed presentation at the JWD Artspace, where Ukrainian Zhanna Kadyrova’s Shots (2014–15), ceramic paving slabs featuring the impact of bullets that create a weblike abstraction, and Palianytsia (2022), a documentary video and sculptures made of found river stones that look like bread (the Ukrainian word for which – a word Russians struggle to pronounce – gives the title), awkwardly sandwich Nengi Omuku’s hanging paintings on Nigerian Sanyan fabric (traditionally moth silk woven with cotton) of moments of crisis and chaos in her homeland. While Omuku’s work chimes with some of the themes proposed by Yee, here her’s and Kadyrova’s overlap to the extent that they confusingly and chaotically almost blend into one. That’s followed by painter Jarasporn Chumsri’s live open studio, in which she paints the locales of the artists that she has been influenced by, using Google Earth as a kind of magic carpet in order to get to her source material (which includes lots of views of Notre-Dame, Paris). Why the painting is necessary, other than for reasons of nostalgia, given the digital tools used to access the imagery, is anyone’s guess. All of which distracts somewhat from Cian Dayrit’s crazed, humorous and dazzling mixed-media (wooden puppets, denim jackets, cloaks, walking sticks, military patches and embroidered prayers) commentaries on militarism, repression and colonialism in his native Philippines. While there are some obvious connecting threads, the ways in which those threads are spread tends more towards a tangled yarn. Or the metaphor provided at the end of the room, in the form of Jompet Kuswidananto’s shattered chandeliers (Terang Boelan, 2022). Given the geography travelled in this one clutterbox of a room, you’re left feeling unsure as to whether the curators are suggesting that all the world’s problems are somehow the same, or that the biennial format simply requires the covering of a lot of ground. Whichever is the case, the experience here is like that of entering a hoarder’s attic.

That’s not to say that the biennale as a whole doesn’t have space to truly present work that’s intriguing, powerful and moving, and to make some clear connections between them. Over at its main venue, the Bangkok Art & Culture Centre (BACC), Arthur Jafa’s seven-minute epic video Love is the Message, The Message is Death (2016), chronicling the triumphs and the brutality of the Black American experience through found footage and a Kanye West soundtrack, chimes eloquently with Sophia Al Maria’s single-channel video Beast Type Song (2019), a metafictional meditation on scripting, rescripting, erasure, revision and the enduring legacies of colonialism, performed through the movements of a string of performers. The retelling, erasing and reclamation resonates, in a different, more straightforward way with the largescale paintings of the APY Art Centre Collective, comprising ten art centres in South Australia, owned and run by the people of the Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands, and featuring the collective practice of up to 500 First Nation artists (not all of whose work is on show here), most of it telling stories related to the land. The collective simultaneously generates income for its generally deprived communities, and offers the Aṉangu the opportunity to tell their stories in a public space. Along the spiral ramp that runs through the BACC, Vasan Sitthiket’s painted shadow puppets of figures who have shaped modernity (from Karl Marx to Donald Trump) adds a more straightforwardly political critique to proceedings. But, in a darker way, all of these connect with Collective Absentia’s (a necessarily mysterious artist research group currently focused on the effects of political violence in Myanmar) disturbing and powerful performance Again and Again (2022). It consists of a barefoot man, dressed in black, wearing a black hood, sitting silently on a chair in a brightly lit but easy-to-miss alcove on the top floor of the exhibition space. As the performer sits there, without food or drink, for the duration of the exhibition’s opening hours, unmoving – no drama, no action – you’re unsure as to whether or not this is chaos or calm. Proof, perhaps, that sometimes the best art comprises the simplest of gestures, because, amidst the general havoc, it feels the most real.

Bangkok Art Biennale: Chaos: Calm, Various venues, Bangkok, through 23 February