Over the past 50 years the artist has built up a body of work at once disarming and tender; one that, above all else, makes us think about how we see the world and our place within it

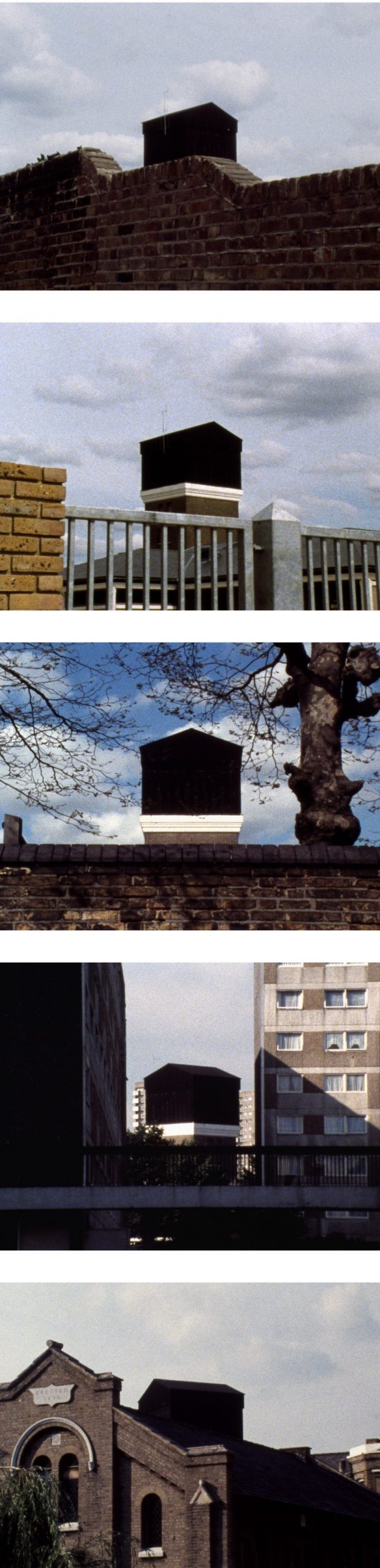

Between 1985 and 1987, John Smith shot the 16mm, 24-minute film The Black Tower, a work whose inventiveness, economy and myriad wrongfooting aspects now stand as a microcosm of the British artist/filmmaker’s continually self-renewing, half-century career. The narrator of The Black Tower – Smith himself, who both scripts and voices virtually all his films – recounts a modern-day gothic horror narrative over fixed-position images, mostly shot outdoors in London. One day he notices the titular edifice, something like a big dark potting shed on top of a tall brick building, looming over a terrace near his home. From then on – spoilers ahead – it follows him wherever he goes: to visit a friend in prison; to the Shropshire countryside for respite from this ominous, pursuant enigma; to hospital after his mental breakdown following a period living indoors and subsisting on ice cream; to the cemetery after he finally, half-involuntarily enters the building and dies, where the story does not, quite, end.

The Black Tower is, in one regard, a postmodernist update on the weird and eerie tales of Victorian-era writers like M.R. James and Arthur Machen. But, typically for Smith, it’s also a whole bunch of other things at once, artfully angled together. It’s a structuralist film: Smith uses all the different viewpoints that the real tower, thanks to its height, could be seen and filmed from – including a pseudo-rustic view through trees, soundtracked by loud birdsong – to suggest it lurks in numerous places, and the specifics of those places drive the twists of the narrative. Bursts of block colour, which initially recall the disjunctive techniques of Jean-Luc Godard, are later revealed as tight closeups of the narrator’s everyday stuff (a mug, a teasmade, a blanket). When Smith’s narrator dreams that he’s inside the tower, and the screen makes one of its periodic cuts to black, he hazards that the room he’s in is both painted black and brightly lit. In a sequence shot through the sequestered narrator’s/Smith’s window, observing the changing foliage on a prominent tree, cars sometimes drive past its trunk and don’t emerge the other side, as if vanishing into an occult abyss. At the film’s midpoint, the narrator says he’s spending most of his time indoors ‘writing this script’, which he describes as ‘dramatic fiction’.

But then, all this play has a political-aesthetic point – that appearances can be deceptive. The Black Tower was filmed, notably, in the midst of Margaret Thatcher’s reign, when the UK’s Conservative government was hiding its cruelties under suggestions that the country was getting back to some kind of sylvan, Brideshead Revisited-type golden age (assisted by a popular 1981 TV remake of the novel). As you watch Smith’s film, you keep reassessing its aims and scope, a hallmark of the artist, and maybe if you see it repeatedly at intervals of years, it changes again for you. I first watched The Black Tower nearly 20 years ago; viewing it again recently, somewhat older – it’s currently part of a three-film presentation at Vienna’s Secession – made me think about what the inescapable tower actually is (if not just a harbinger of someone losing their mind). Depression, à la Winston Churchill’s ‘black dog’? The inevitability of death? As with the gothic tales that precede it, this film gains from its unexplained aspects, but equally functions as primo deconstruction that jumps the fences of formalism; it’s also mordantly funny. This is the kind of thing that Smith is nonpareil at doing, and it’s how he makes his implicit sociological points so palatable.

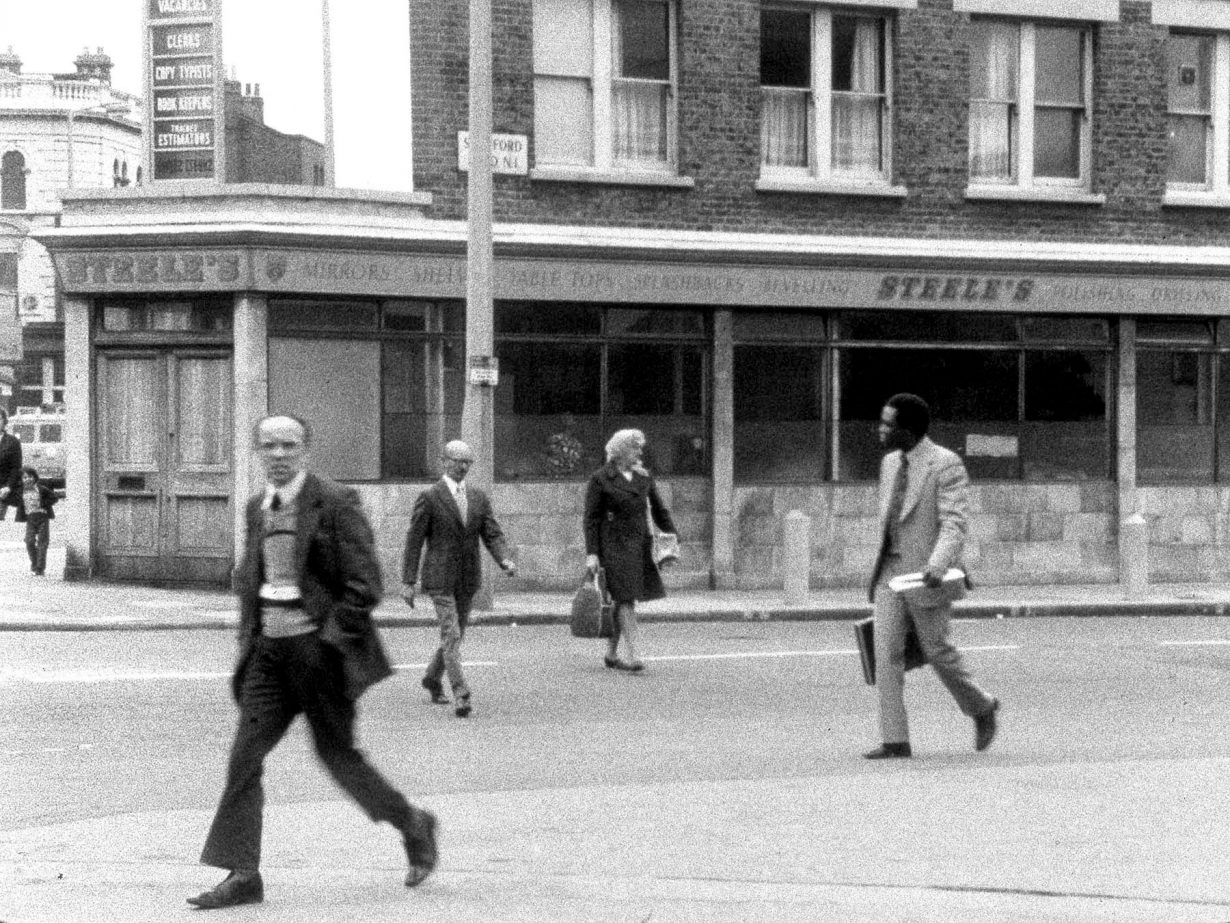

Such was evident as far back as 1976, when, at age twenty-four, while still a student at the Royal College of Art, he made the now-classic black-and-white film The Girl Chewing Gum. For this, Smith filmed the goings-on at a street corner in then down-at-heel Dalston, East London: pedestrians, pigeons, passing cars. He then recorded an omnipotent voiceover in which he appeared to be directing this chancy action (“Now I want the old man with white hair and glasses to cross the road. Come on, quickly!” – cue old man). But then, gag established and viewer sucked in, he begins discussing the demographic makeup of the area, immigrant labour and inequality; and, finally, pulls apart the film’s illusions a couple more times – ‘revealing’, for instance, that he is recording his voiceover from a field miles away, and then telling new stories about the people in Dalston, as if to establish that when image and language are put together, narrative and truth become fluid. And yet, within this fluidity and urging that the viewer keep their eyes open, Smith finds truths about society and the deceptive power of media.

Over the last half-century, he’s managed this balance in untold ways, from tracking how communities were being displaced by the wrecker’s balls and the imposition of new roads in East London in Blight (1994–96) to the seven-part Hotel Diaries (2001–07), wherein Smith ruminates, seemingly unscripted, on global strife in and around a series of hotel rooms. These works, which often involve a TV playing stage-managed footage of a current war, seem casual but are actually pointedly choreographed: in Museum Piece (2004), shot during US assaults on Falluja, Iraq, Smith, who’s been monologuing partly on Second World War history, finds an object made by Siemens, notes the company’s Nazi history, leaves his room and enters an elevator made by the Schindler company and thus, yes, “Schindler’s Lift”. The narrator, and the narration, are unreliable; the viewer is provoked into a useful suspiciousness.

Part of Smith’s achievement, though, is to trouble any given reading of his work as merely exploring how words and images can dangerously intersect. His art, in finding the wide potentialities within everyday objects and environments, can be surprisingly tender, if never quite sentimental, and it has ruminated ever more on time passing and mortality. See, for example, Dad’s Stick, commissioned for the Frieze Art Fair in 2012 (and also in the Secession show). This film, themed around two sticklike objects that Smith appears to have inherited from his accountant father, opens on a wavering, rainbow-coloured, initially incongruous painted landscape of stacked, hilly lines, while Smith talks about his dad, “a perfectionist with a steady hand”, who stands for a lost, seemingly more decent age: a man who had two jobs in his life, who kept a cylindrical ruler from his first job and converted it into a truncheon – cue still image of same – in case he ever became a have-a-go hero.

The initial landscape, we realise (or are told), is a cross-section of a stirring stick that Smith Sr used while painting the walls of their various abodes, and that he later cut down so he could see, all at once, his amateur-painter past and his changing colour preferences laid out in rings. This image/object is something like an agate that compresses a past of dependable employment, civic duty and responsible homemaking, if not a romanticised past (Smith’s father beat him sometimes, the son remembers, but not often and not with the truncheon). The closing credits establish that Smith’s father died in 2007. You assume the son is telling the truth here; but it’s Smith, so you can’t be entirely sure; you’re moved but watchful. All this – a suburban emotional rollercoaster, a story both personal and generational – is dispatched within five minutes.

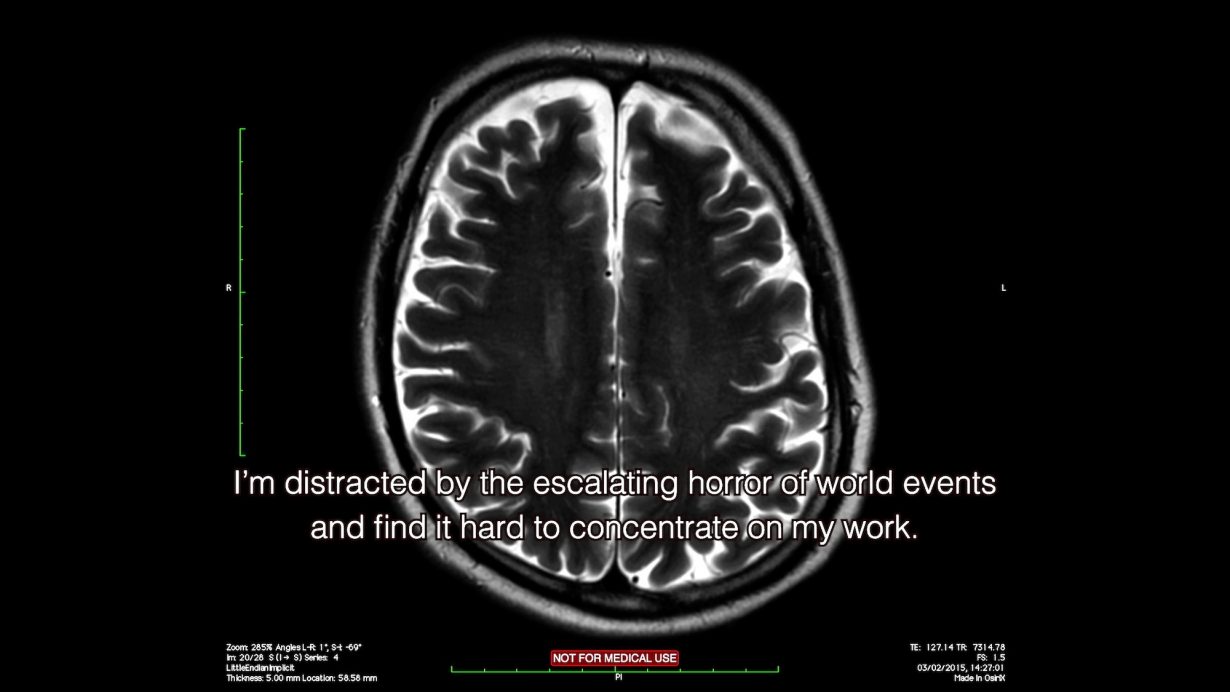

And yet in some ways this seems like a mere runup for the complexly autobiographical Being John Smith (2024), the third film in Smith’s Secession presentation. This 27-minute work, with voiceover by the artist as usual, begins as if it’s going to be an oddly conventional, autumnal trawl through Smith’s own life and how his colourless name has shaped it, mixing family photos, school reports, pictures of a long-haired Smith at college, etc. But a few minutes in, it shifts tone via captions, first talking about how Smith has grown more leftist as he’s gotten older (followed by ‘Stop the genocide. Ceasefire now’), then probing his own anxieties and opening up about health issues: the artist, we learn, is uncertain of his thinking processes following treatment for “head and neck cancer” three years earlier; this is his first work since. He’s also distracted by “the escalating horror of world events”, predicts that “the human race will soon be extinct”, wonders accordingly why artists are increasingly making archives for posterity since “cockroaches can’t read” and says he lacks confidence in making art now, doesn’t like hearing his voice.

Amid this, while pulling the film in two directions, he nevertheless continues narrating his own life and addresses how “being called John Smith still undermines my sense of individuality and self-worth”; he’s not even, he notes, the most famous and googleable John Smith involved in film – that’d be a character from Disney’s Pocahontas. (The wit is undimmed, though: Smith points out that an upside of his moniker is that when he has to fill out digital signatures online, his name is usually already there.) The film ends, comic-redemptively and via an anecdote about Smith having taught Jarvis Cocker at Saint Martin’s, with Smith in a VIP box (which reminds him of the Black Tower) at a Pulp concert, thousands of people singing “I wanna live with common people like you”, and the artist pointing out that there are currently 30,000 John Smiths in the UK. But it’s the one and only John Smith, filmmaker, making this film – which has been periodically, self-mockingly intercut with the sound of a wailing baby – so the last thing he notes is that he’s “not sure what I think about this ending”.

It’s an extraordinary work, further proof of Smith’s abilities to wring diverse feeling-tones – like whatever you’d call the combination of certitude and doubt – from the ‘ordinary’, illuminating the depths behind the ostensibly humdrum. The film plays games but is, simultaneously and wrenchingly, done with playing games; and it confirms once again that this man’s name is the only ordinary thing about him and the arc of his creative life. “I’ve come to accept”, says the then seventy-one-year-old Smith early in the film, “that I might have made my best work before I was seventy.” Being John Smith begs, in the strongest terms, to differ.

John Smith: Being John Smith is on view at Secession, Vienna, through 16 November

From the October 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.

Read next J.J. Charlesworth’s review of a John Smith ‘Solo Show’ in 2010