For the better part of 50 years, the American artist has itemised social injustices plaguing the modern world in episodic paintings

Even at one’s most vigilant, is it possible to acknowledge every iniquity, to trace every filament of systemic racism? The work of Ben Sakoguchi attempts to do just that. For the better part of 50 years, he has itemised social injustices plaguing the modern world in episodic paintings like the ongoing series Orange Crate Labels (c. 1975–), 27 of which appear in his exhibition at Bel Ami, Los Angeles. The Orange Crate paintings are one of those rare artistic projects that can span a life without losing vigour, thanks to the artist’s knack for compositional variation and a strict adherence to parameters – not to mention his limitless, bitter muse: human cruelty. Its rules are as follows: the painting must include a title; the words ‘brand’, ‘California’ and ‘oranges’; the name of a California city or other location; and what Sakoguchi calls a ‘visual orange’, ie an image of the fruit itself. All other content must respond to these elements and do so within the bounds of a 25-by-28 cm swatch of canvas. The dimensions, the tags and the visual orange all pay tribute to the artist’s early study of labels on the orange crates delivered to his family’s San Bernardino grocery store – a business the parents operated after their release from the Poston Internment Camp in Arizona, where they, Ben (born in 1938) and Ben’s three siblings had spent the Second World War, alongside more than 17,000 other incarcerated Japanese and Japanese-American people.

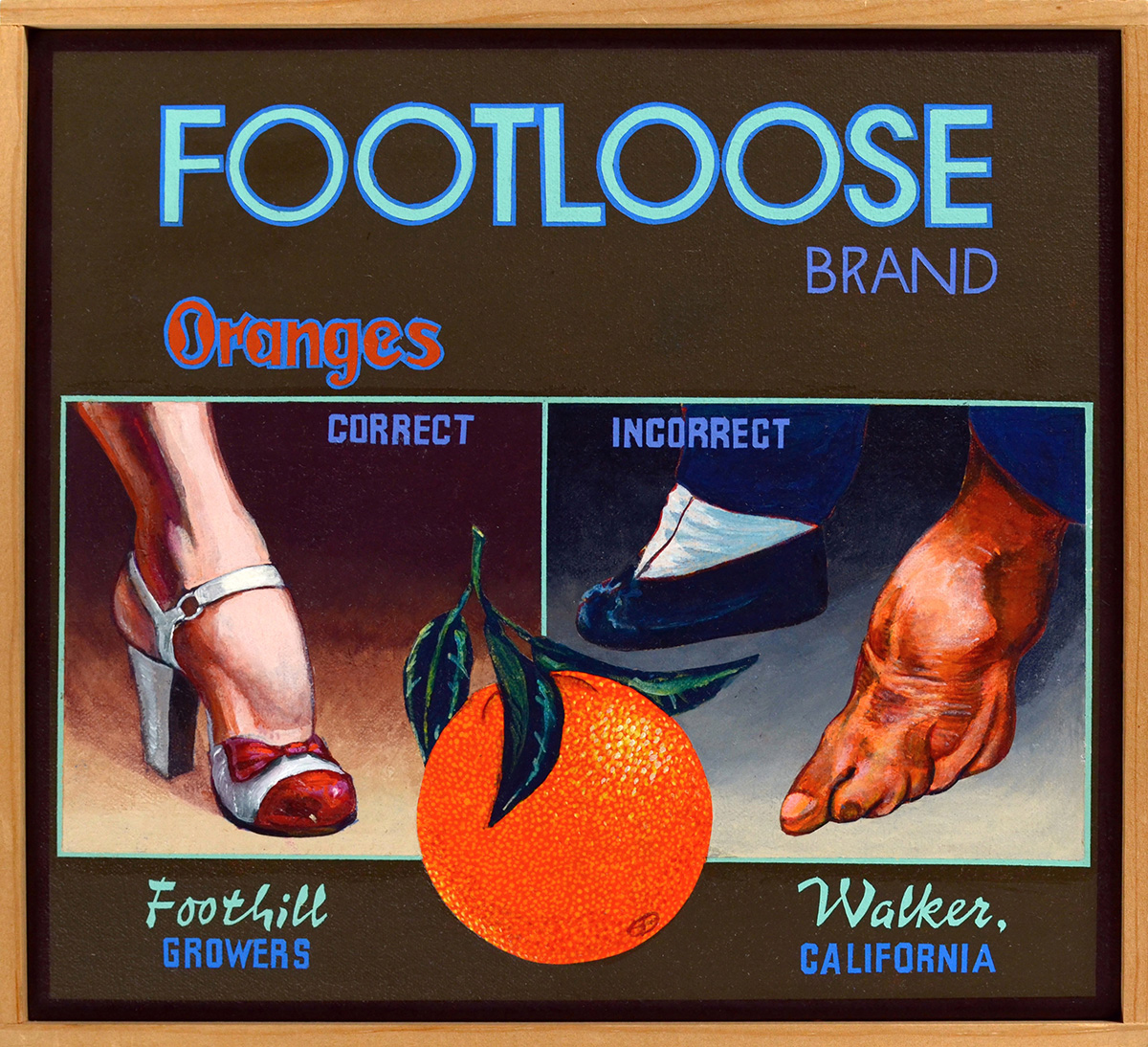

Rage is often described as the emotional undercurrent streaming through Sakoguchi’s work. The fountainhead, one might surmise, lies in the Poston experience. Two Orange Crate paintings at Bel Ami present examples of the anti-Asian sentiment ingrained within the American psyche that contributed to such state-sanctioned xenophobia. In the first, Footloose Brand (1995), the feet of two women are depicted. On the left, a white woman’s foot, strapped into a high-heeled sandal, is planted firmly against a beige ground; on the right, a Chinese woman’s foot, altered by binding, settles against a blue ground. Above the former floats the word ‘correct’; above the latter, ‘incorrect’. The implications of this binary image are clear enough: though both Eastern and Western cultures impose extreme bodily discomfort on women in the name of beauty, the cultural practices of the East, exemplified by an ancient Chinese custom, are unfathomable to American perception. The painting exposes the unwillingness of America to gaze upon its own intractable hypocrisy or recognise the pain it inflicts upon its female population, and it lays bare, with greater vitriol, America’s view of Asia as a bizarre foreign land.

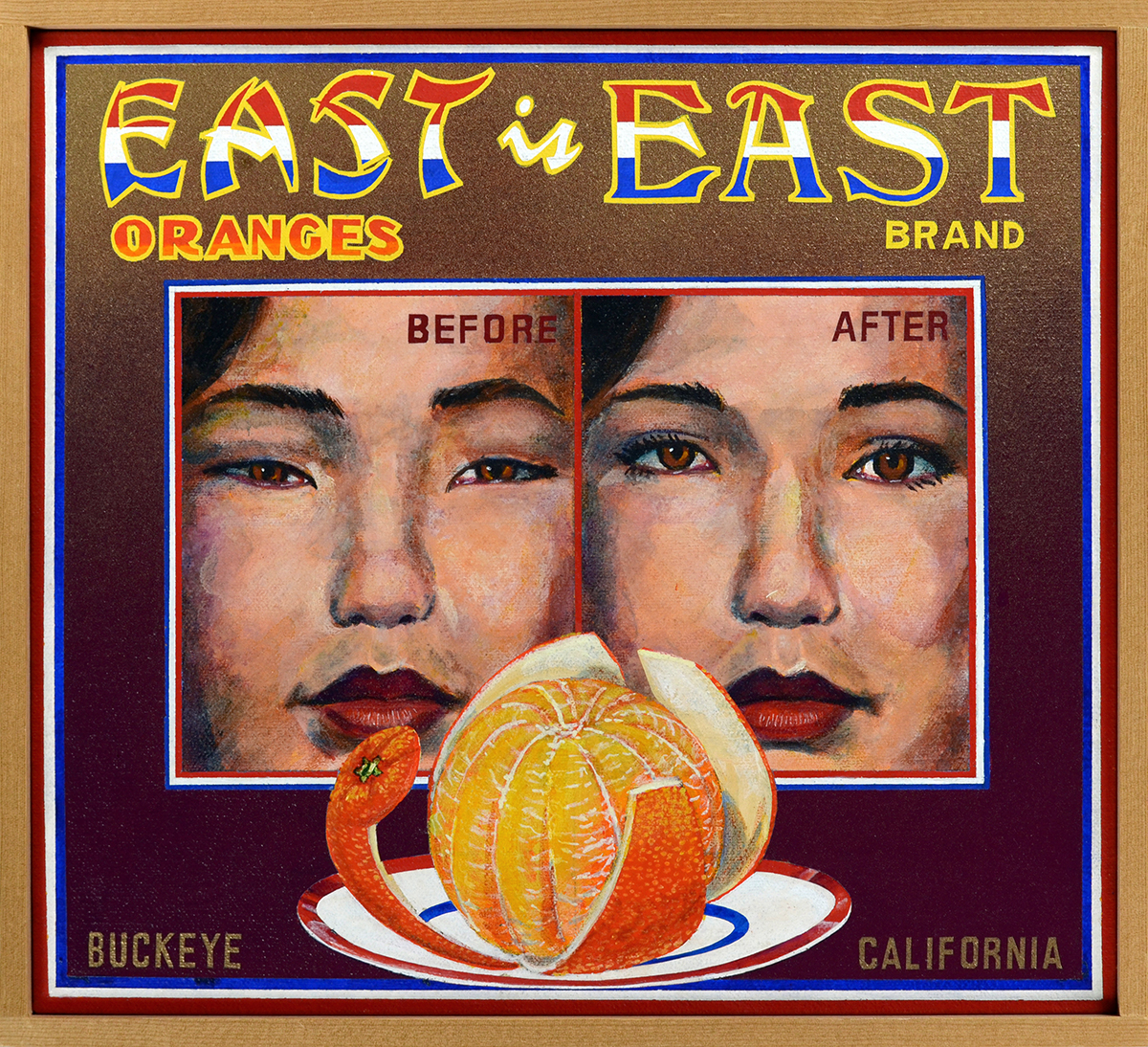

The examination of female beauty linked to race relations in the United States recurs in East is East Brand (2001). Again, the composition is organised in two halves, inviting a compare-contrast analysis. In both halves an Asian woman’s face fills the frame, but the eyelids of the woman on the left are narrower than those of the woman on the right. Informed by the words ‘before’ and ‘after’ captioning the left and right windows, respectively, viewers are meant to deduce that they see the same woman’s face before and after blepharoplasty. The words ‘EAST is EAST’ headline the painting, with pointed duality: the first EAST is rendered in a faux ‘bamboo brush’-style typeface; the second is rendered in a serif font with sweeping elements that imply concordance with the orientalised letterforms nearby. Both are banded with red, white and blue stripes, indicating absorption within an American idiom, albeit one that denies global diversity but prefers to imagine Asian culture as a monoculture and Asian-American culture as American-aspirant, an appalling prospect that is redoubled when one realises the same conditions apply to the woman’s portraits. The jump from typefaces to human faces is a reminder of how social constructs lock anyone considered ‘other’ into a social matrix wherein their identity is subsumed by negative stereotypes, no matter how radically they submit their identity to said matrix’s standards.

As in many Orange Crate paintings, an orange occupies the foreground of East is East Brand. In this instance, the skin has been sliced away from its endocarp with precision. The correlation between the surgical intervention on the woman’s face and the exacting removal of the orange’s peel begs the question of the fruit’s relationship to the imagery it chaperones. To what degree does it operate symbolically? To what extent does it recapitulate the painting’s thematic concerns? An elastic interpretation thinks the orange akin to an animated ball that leads singalongs in karaoke videos, but instead of bouncing from lyric to lyric, it bounces from frame to frame, multiplying and diversifying as it leads the viewer down a tour of Sakoguchi’s exhaustive and often caustic satirical registry.

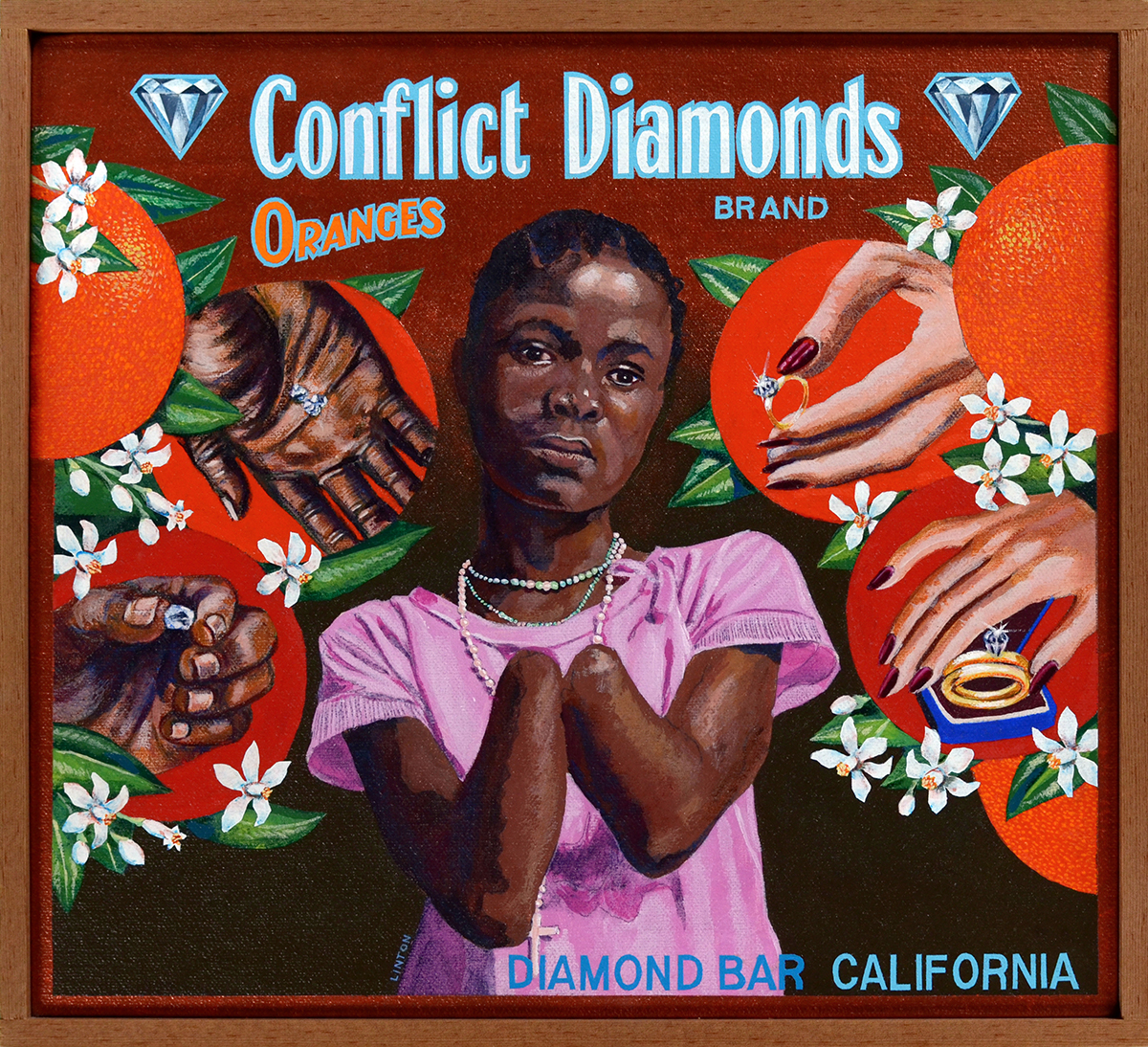

At times the orange’s state bears a sly connection to the topic on trial, offering meta-commentary about the subject matter, as in East is East Brand, and at other times it serves to enrich the painting’s narrative as a compositional device. In, say, Conflict Diamonds Brand (2002) orange-coloured disks circumscribe Black-skinned hands holding raw diamonds and white-skinned hands holding diamond jewellery. The vignettes flank a girl whose arms end at the wrists. Context clues and a cursory knowledge of the diamond industry’s blood-saturated complicity with, for example, the Revolutionary United Front – the rebel army that commandeered diamond mines to fund an insurgency and amputated the hands, arms and legs of untold thousands in acts of terrorism during Sierra Leone’s civil war (1991–2002) – lead one to conclude, with reasonable confidence, that the girl represents the war-wounded at their most innocent. The disembodied hands, those agents of corrupt merchantry, seem especially cruel in proximity to the maimed figure, who cannot hold a fork, wear a ring or peel any hesperidia.

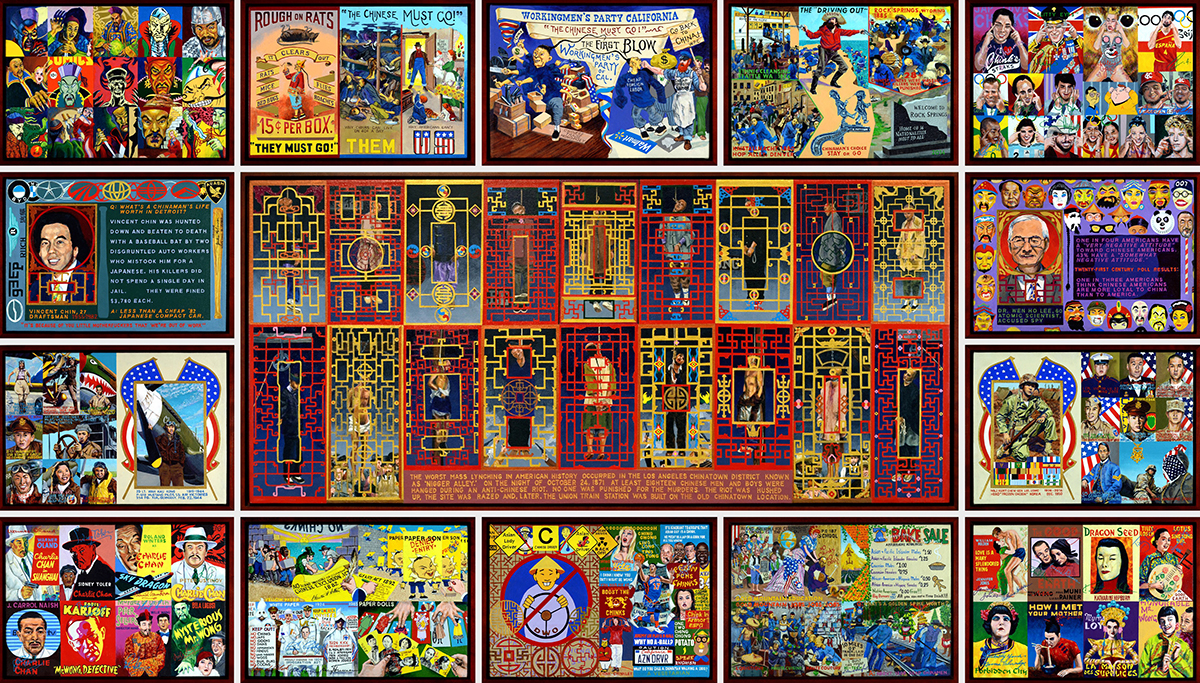

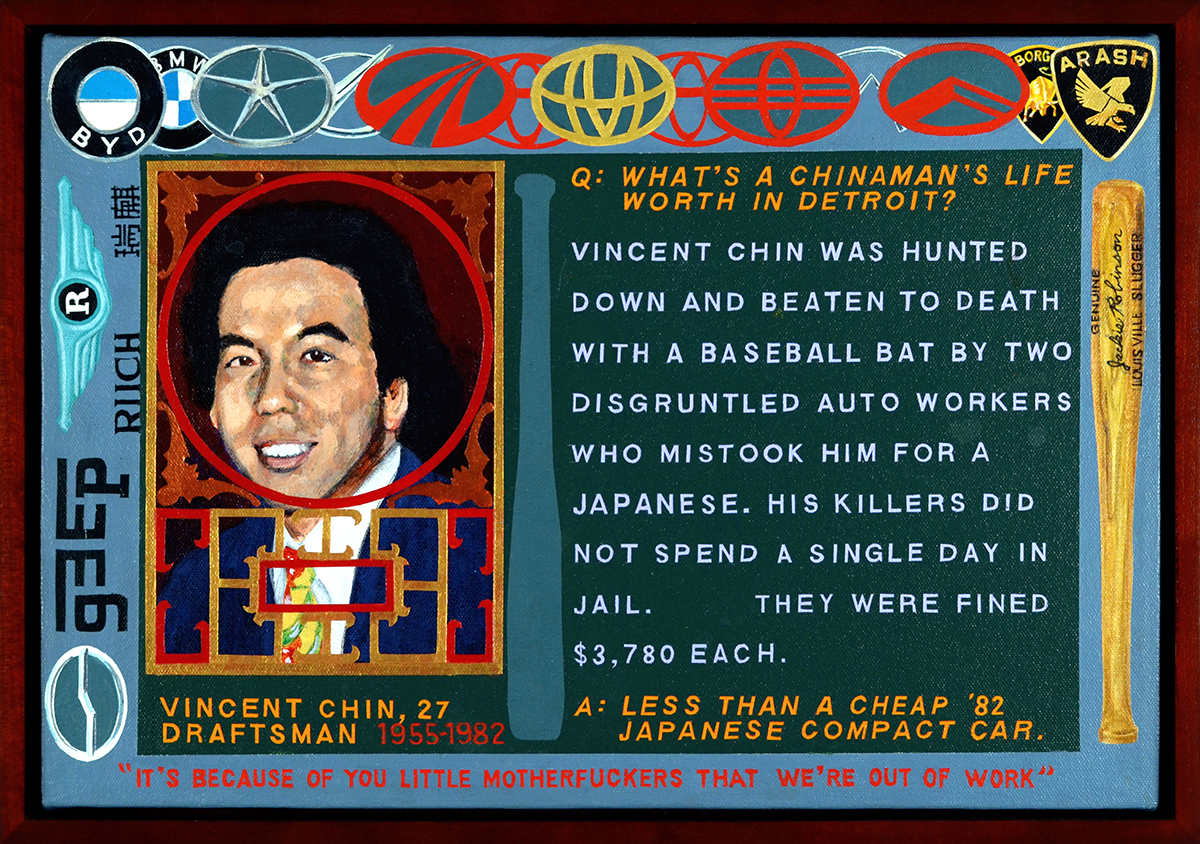

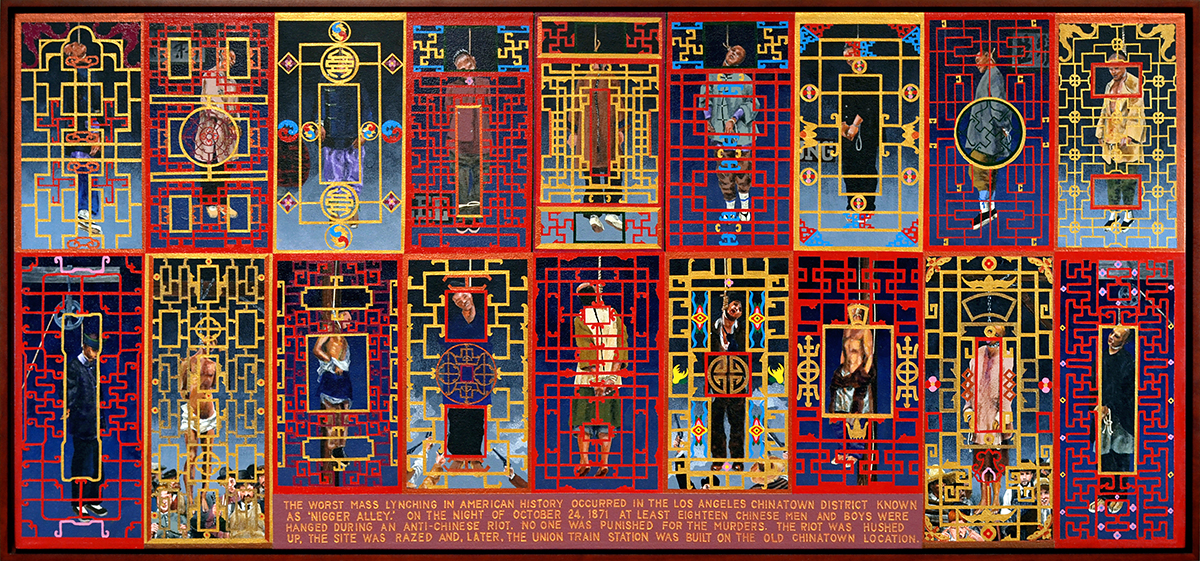

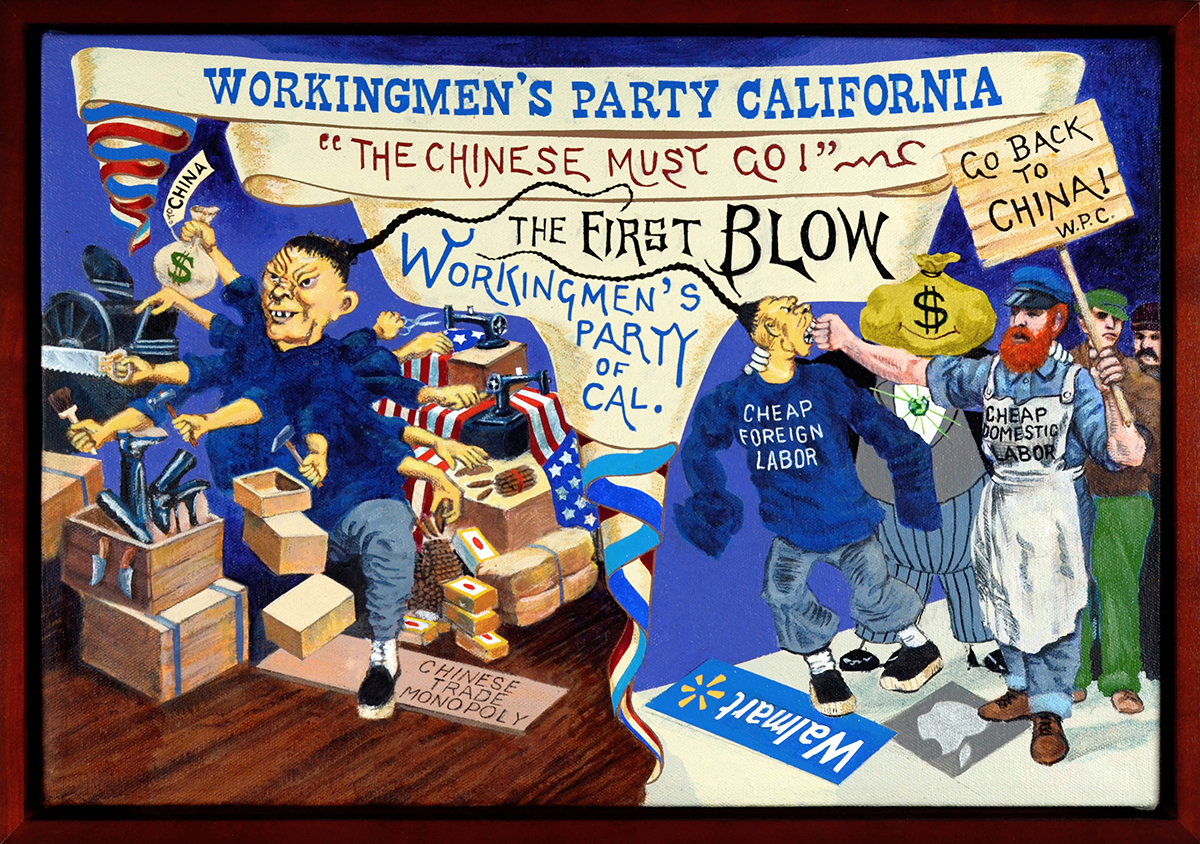

Although extensive, Orange Crate Labels constitutes but one strain of Sakoguchi’s practice, and there are zones within his work where the orange, a symbol of paradise even when rotten, dares not roll. The 15-panel painting Chinatown (2014), also displayed at Bel Ami (hence the show’s title), constitutes one such zone. The central and largest panel, around which the others form a border, memorialises the 18 Chinese men and boys who were killed by a mob in Los Angeles’s Old Chinatown during the Chinese Massacre of 1871. The incident – precipitated by homegrown bigotry coupled with rampant anti-Chinese resentment tied to labour disputes during California’s early statehood – is known as the largest mass lynching in American history. Sakoguchi spares no delicate sensibilities in his depiction of the event. The bodies hang, some stripped to the waist, all terribly bent; each is framed within his own latticed window. Two windows contain jeering crowds gathered below the corpses. In one, a woman pulls the corners of her eyes back with index fingers, mocking the face of the dead man. Her gesture punctuates, with sickening precision, the gross disregard for human life that permitted the massacre to unfold, an atrocity Sakoguchi beseeches his viewers to reckon with both in its own right and as an event with lasting ramifications.

The surrounding panels of the Chinatown painting enumerate some of these ramifications. In the top right canvas, a roster of contemporary popular culture icons repeat the mocking gesture described above, while canvases in the other three corners cite the many instances of ‘yellowface’ in American film, television and comics. Laterally and longitudinally, further negative stereotypes about the morality and general aptitude of East Asians abound, all of which demand, as an ethical imperative, greater critical dissection than is possible here. What is possible to comprehend at the superficial level, however, is the cultural trauma incurred by the Massacre of 1871 and like atrocities, which perpetuates by degree, if not in kind, the dehumanisation of a people by the mainstream forces of a white nation. Los Angeles’s Union Station now stands where Old Chinatown used to be, where those men and boys were hanged on a fearsome night in 1871. New Chinatown lies just north of the site, built by a displaced community; it is home to Bel Ami. That the gallery mounted Sakoguchi’s exhibition is no coincidence, given its location. The programme represents, at the level of local politics and within the larger debate on gentrification, an effort by a commercial gallery to engage the neighbourhood where it operates in a self-reflexive and compensatory manner. Although no one deserves a trophy for decent behaviour, Bel Ami’s effort is commendable and unfortunately all too rare among the gallery circuit. And while Bel Ami has certainly not co-opted another’s pain – the gallery make no claims of ownership or privilege over Sakoguchi’s voice – it has given it prominence to great effect. Would that others with similar resources do the same.

Ben Sakoguchi: Chinatown at Bel Ami, Los Angeles, 6 March – 15 May