As the opening day of Billie Zangewa’s show drew to a close, few would have anticipated the circumstances that would soon engulf it, nor the new resonances her work would find in light of them. While visitors trickled out of Galerie Templon, Emmanuel Macron announced new measures to combat COVID-19. In the days that followed, the country went into lockdown: the gallery closed its doors; daily life changed for everyone.

Born in Malawi and based in Johannesburg, Zangewa creates embroidered silk works that celebrate those aspects of the day-to-day that pass unnoticed until they are gone: a school run, a swimming lesson, a birthday party with friends. The importance of the everyday is embedded in the choice of her medium. In interviews she has described how the appeal of textile lies in how it constitutes a universal, sensory experience that punctuates all our daily lives. In a show that focuses on love, touch is also the point of contact between the individual and the external world, the physical encounter between self and other. This is nowhere more apparent than in Soldier of Love (2020), which depicts the artist walking her young son to school, his hand in hers. Her body leans towards his, the viewer can almost feel his weight pulling on her. The work’s title evokes the show’s central theme: the duality of love and struggle that underpins existence. It would be easy to dismiss as a cliché, but sometimes the most well-worn phrases contain the greatest truths.

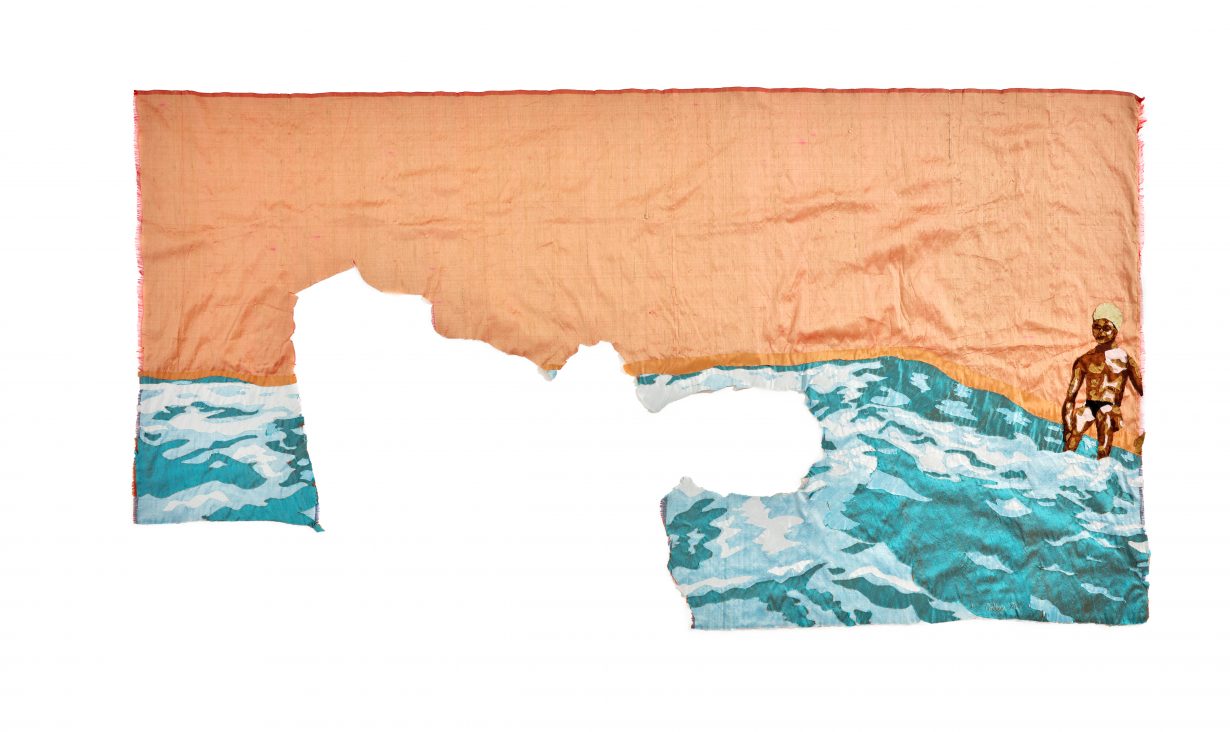

Zangewa is the protagonist in all but three of the ten tapestries exhibited, where identity is conveyed as multiple, contradictory and above all constructed through its everyday expression. The serene domestic scenes of Sunday Morning Pursuits (2020) – browsing the newspaper – or Cold Shower (2019) contrast with the more anguished self-portrait Am I Enough? (2020). In this simple composition, stripped of background noise, the artist confronts the viewer, naked. The title’s question reverberates in the hesitancy of her pose, at once defiant as she presents her body to the viewer, but also uncomfortable, as she looks away, refusing to meet that gaze. The artist uses her medium to full advantage: her body is sewn from fragments of silk that reflect the way the light hits her skin, but also evoke a self in construction, assembled and reassembled. The torn sections in the tapestry are a frequent feature of Zangewa’s work, and speak, as the artist has described, to the darker, more traumatic aspects of experience, present but never fully revealed to the viewer. This practice reappears in The Swimming Lesson (2020), the largest and perhaps most emotionally charged work in the exhibition. Here, the artist’s son sits alone on the side of a swimming pool; vast swathes of cloth missing from the foreground indicate the absence of figures from the original scene – the swimming instructor and Zangewa herself. The work captures the simultaneous distress of a parent forced to relinquish control, and the joy of seeing that child grow into an autonomous adult.

One of the exhibition’s most striking works is Birthday Party (2020), a bright, busy composition where friends and family gather around a table. Unlike the other works on show, the characters are depicted without facial features, the traits of individuality suppressed to accentuate the collective energy of the scene and to mark the passage from the particular to the universal. Zangewa’s works don’t need a pandemic to be appreciated, but perhaps now more than ever we understand why it is the minutiae of the everyday, and the relationships that play out within it, that we should all be celebrating.

Billie Zangewa: Soldier of Love, Galerie Templon, Paris, 14 March – 6 June