The late artist’s riffs on Renaissance and Baroque works are vividly alive

In 1961 a twenty-four-year-old Bob Thompson left New York and the beatnik circles in which he moved for the museums of Europe, seeking out the Old Masters who were already inspiring his own paintings. Five years later, Thompson died of an overdose, leaving behind roughly a thousand paintings and drawings. Six paintings made between 1960 and 1964 comprise Bob Thompson: Measure of My Song, three of which rework historic sources. No dry academic studies, these – his riffs on Renaissance and Baroque works are vividly alive, painted fast and with great feeling. Figures flatten into silhouettes with few features, colour humming where detail once was.

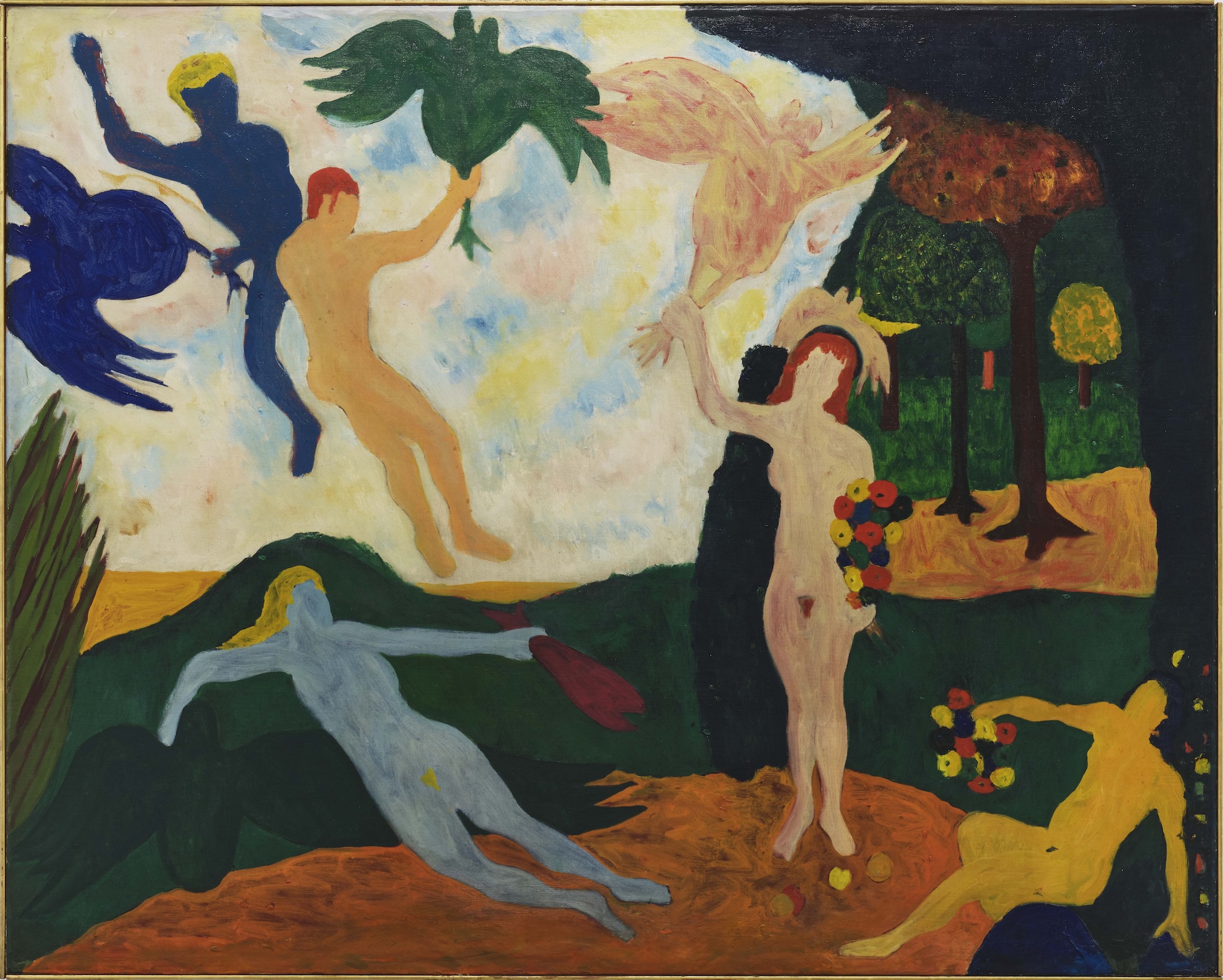

Two large paintings from 1964 anchor the exhibition: Abundance of the Four Elements (titled after a 1606 painting by Hendrik de Clerck and Bruegel the Elder) and Perseus and Andromeda, after Titian’s 1554–56 painting of the same name, which Thompson likely saw at the Wallace Collection in London. In Abundance Thompson replaces the putti flying over Ceres, goddess of fertility and agriculture, with the gnomic turkeylike creatures that appear throughout his work. The goddess wields one bird by the feet, as do the allegorical figures of Air and Fire. The original’s brimming sense of plenty remains, however, in the flowers simplified to donutlike rings of colour. In Perseus and Andromeda, Titian’s erotic spectacle is more dramatically rescored: Perseus’s drapery has gone, replaced by a matter-of-fact phallus; Andromeda’s chains have vanished, her pose more that of a dancer than a prisoner. The hero’s sword has morphed into something like a turkey with spread wings – a symbol of masculinity comically inverted, and a canonical image transformed into an allegory for the gender politics of the artist’s own time.

Thompson’s style is that of a man in a tearing hurry. In Untitled (Triptych) (c. 1960), three hinged wooden panels presented on a plinth, dried lumps of paint caught in the wet, speak of speed over care. Each panel shows solid-black couples having sex in a candy-coloured landscape, their undifferentiated outlines forming strange composites. Its mood is feverish, uneasy. This blacking-out invokes censorship; as a Black man from Kentucky, which still had anti-miscegenation laws, married to a white woman, sex here perhaps reflects the weight of racial tensions – even in a psychedelic Arcadia.

The Casting of the Spell (1960), also painted on scrap wood, uses a narrow plank for a friezelike composition filled with figures. From the outstretched arm of the largest shoots a swipe of white paint that cuts across the scene; a fat daub on another suggests impact. Is this a spell being cast, or a shooting? With all detail traded for flat colour – figures in blue, ochre, grey, black against a rapeseed-yellow landscape – its forms are ambiguous, its meaning elusive. Nearby, Turkey Catch (1963) turns his recurring bird motifs into symbols of unruly vitality. Female figures seize them by the feet and a Smurf-blue woman wrings one by the neck, yet her pose recalls that of a Madonna and Child. The final work, Inferno (1963), is perhaps the least successful, veering towards headshop psychedelia despite drawing on El Greco’s elongated figures and Goya’s Los Caprichos (1797–98): Goya’s satirical donkey becomes an ambiguous pale-faced creature, his swarming bats a Bosch-like humanoid.

This could easily become a spot-the-reference game, yet Thompson’s freewheeling exuberance keeps it from feeling so literal. Friend of Ornette Coleman and Nina Simone, Thompson was also a drummer, playing obsessively between painting sessions. It’s not hard to see the logic of jazz here: improvisation, repetition, variation – familiar motifs and compositions used as raw material. As artists such as Kerry James Marshall, Kehinde Wiley, Mickalene Thomas and others recast Western art history with a Black American lens, Thompson’s continuing relevance is clear – yet his work shines in its sheer singularity.

Measure of My Song at Maximillian William, London, through 13 December

Read next How Kerry James Marshall restored Black figures to the western canon