Artworks are outnumbered by stylish photographs of starving artists in their natural habits in Bohemia: History of an Idea, in which romanticised squalor takes precedent over historical awareness

Spread across two floors, this exhibition blends art with documentary, fashion and archival photography to tell a story about ‘Bohemianism’. And though it includes one small subsection on Prague, the show’s LA-based curator, Russell Ferguson, isn’t referring to the citizens of the real Bohemia (ie the Czech people), but rather to an imaginary cosmopolitan, glitzily destitute community of postwar artists, writers, musicians and hangers-on living in various cities. Some of the scenes we see here (Paris, New York, London) are known to us; others (Tehran, Prague, Zagreb) much less so. This creates a split between Western, capitalist milieus publicly remembered for their indefinable air of ‘cool’ and those with less symbolic power or, effectively, cultural capital. This deficit of historical awareness cannot help but be reflected in how the exhibition is organised: aching chic (the basement) separated from what happens decades later in peripheral places (the first floor).

The basement gives us plenty of images of things we intuitively feel we know something about already: there’s chain-smoking ennui in 1950s Paris, with photographs of doe-eyed young lovers from Ed van der Elsken’s series Een Liefdesgeschiedenis in Saint-Germain-des-Prés (Love on the Left Bank, 1950–54). There’s jive talking in early 1960s New York with images of Willem de Kooning by Rudy Burckhardt, and Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac by Fred W. McDarrah. There’s groovy free love in ‘Swinging London’ with David Bailey’s images of an angelically unwrinkled Mick Jagger (1964), the moody threat of gangsters Reggie and Ronnie Kray (1965) and the level gaze of Penelope Tree (1967) during a party.

We see all this end in two images titled Altamont (1969) by Bill Owens, the rock festival that notoriously concluded in multiple deaths, and be reborn in the almost apocalyptic conditions of New York City a decade later: the battered, crumbling Crosby Street, Soho, New York 1978 (1978) by Thomas Struth, the glowering tenement buildings against a darkening flame-licked sky in Martin Wong’s painting Sweet Oblivion (1983) and the bedsit debris, sad lovers, gaunt starers and dreamy smoking trash-punk princess in Trixie on the Cot, New York City (1979) from Nan Goldin’s slideshow The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1979–). It is, however, the fragments from 1980s Tehran, Prague and Zagreb elsewhere on the first floor that compel; even if there’s not enough of this, it opens the possibility that more will be said about these places in the future.

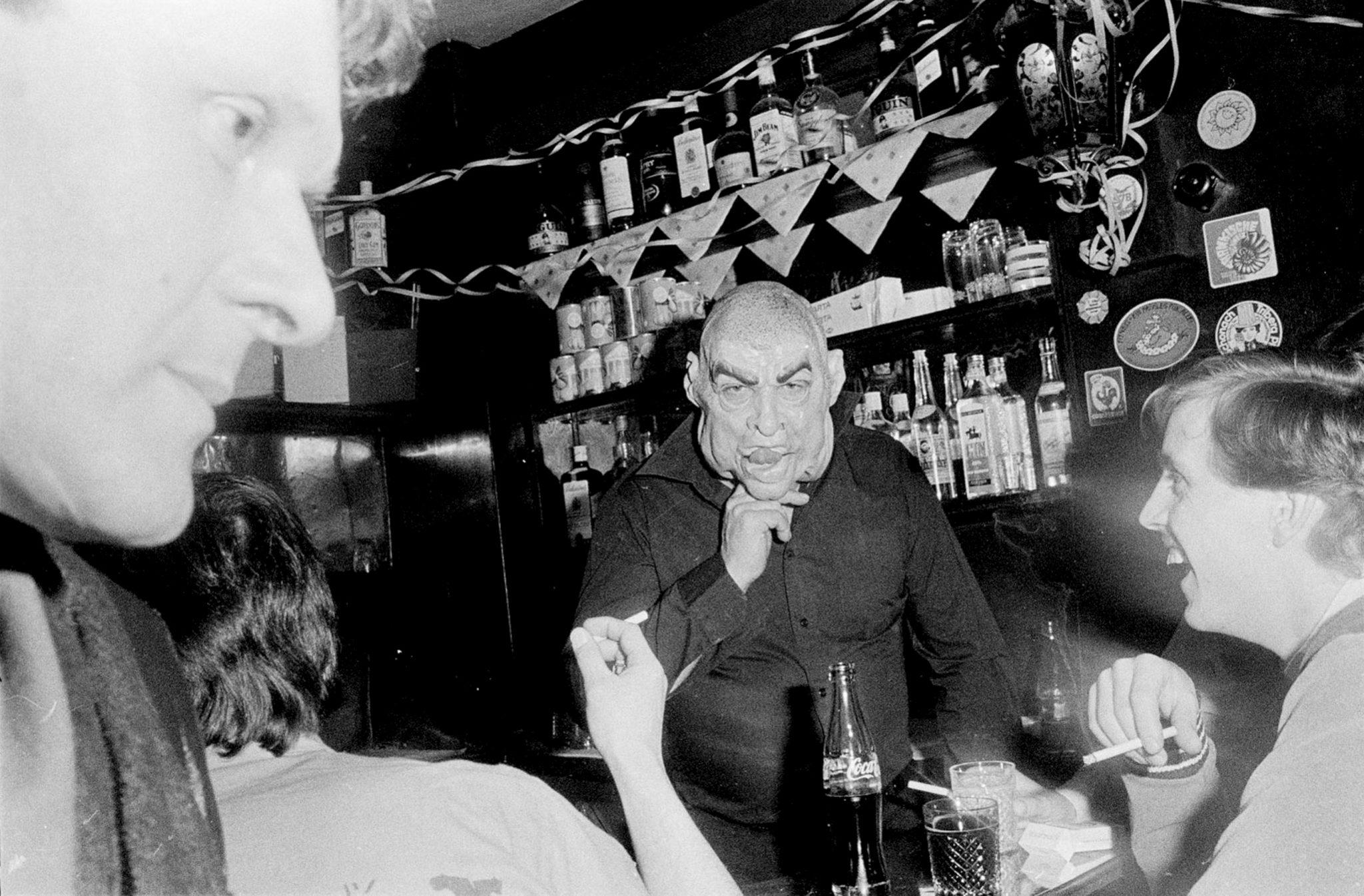

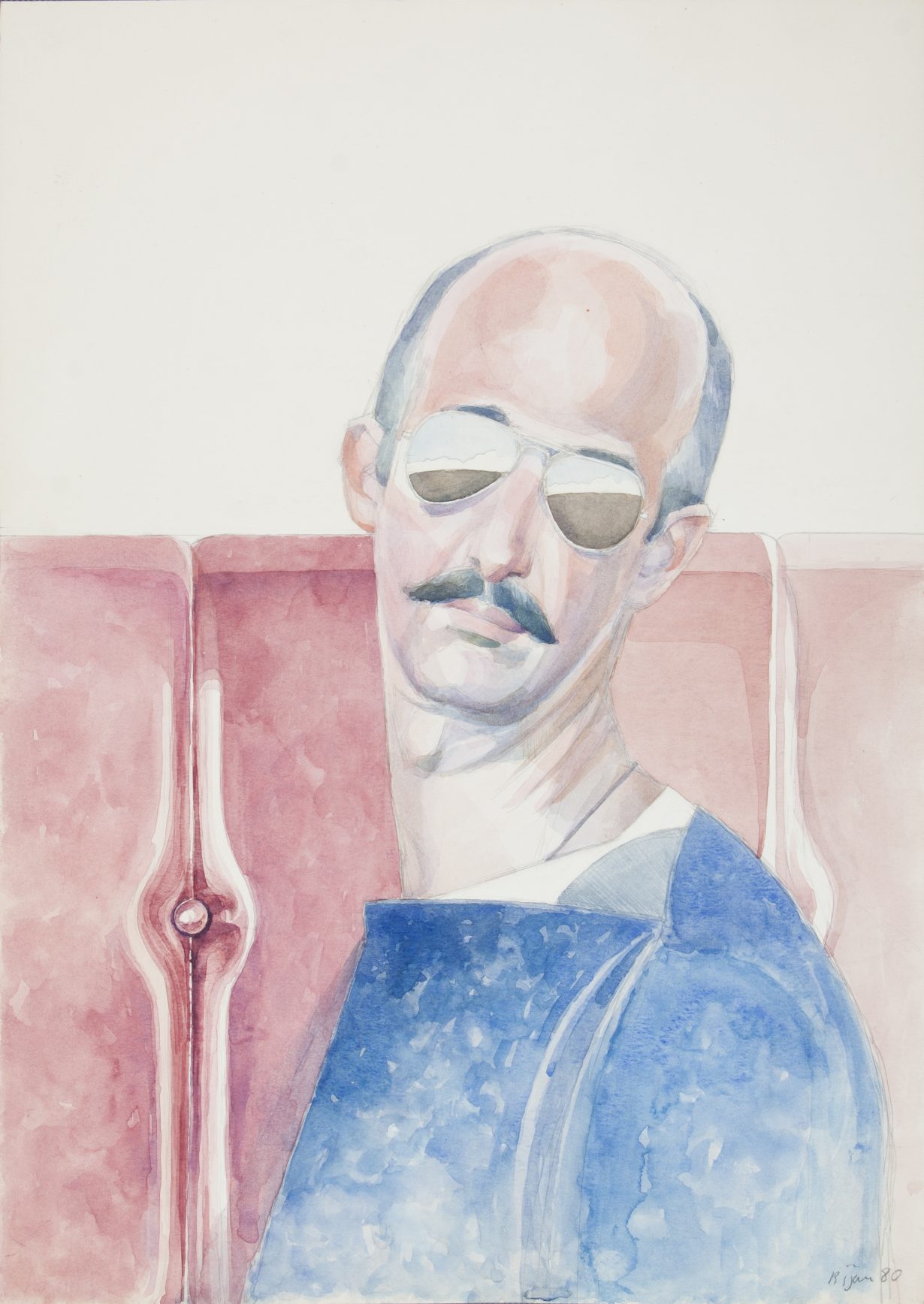

Three drawings by Bijan Saffari – the moustached artist gazing aloof in aviator shades in Untitled (Self-Portrait) (1980), a shirtless man in Untitled (Davood) (1982), a serene sitter in Untitled (Majid Mozaffari) (1976) – offer a window on the secret history of gay life in Tehran just before and after the Iranian Revolution (1979). Meanwhile, six black-and-white photographs from Libuše Jarcovjáková’s 1980s T-Club series document the raucous fun of Prague’s underground lesbian dive bars, and naked bodies in squalid apartments, during a particularly grim and sexless period of communism after the 1968 Soviet invasion and the ensuing repressive period of ‘normalisation’.

There’s more nudity, meanwhile, in four photographic stills from provocateur Tomislav Gotovac’s performance Zagreb, volim te! (Zagreb, I love you!, 1981), in which the artist himself – a huge, bald physical presence – storms down the streets with arms aloft, kisses the tarmac, and tries to catch a tram before being arrested by a stern-faced cop. Creeping dawn sheds light on the aftermath of a wild party (bottles, cups, mess, dangling fairy lights) in Wolfgang Tillmans’s photo wake (2001), suggesting Bohemia’s dancing days are done. Perhaps the good times can still roll on, but the wretched influence of gentrification and online commodification means we can’t help but be sceptical that we can find these conditions (big spaces, cheap rent) again.

Bohemia: History of an Idea nevertheless faces two problems: one is that the stylish photographs of bohemians in their natural habitat, which greatly outnumber works of art here, give us a better sense of contemporary art’s prehistory and preconditions than many of the ‘actual’ works. The other concerns the texture of bohemian life: while Ferguson’s expanded bohemia begins to widen our sense of which scenes are worth looking at or understanding, and how geopolitics plays a role in this, those values are only really legible to people who already have an idea of what bohemian life is like, forever on the fringes of romanticised squalor.

Bohemia: History of an Idea, 1950–2000 at Kunsthalle Praha, Prague, through 16 October