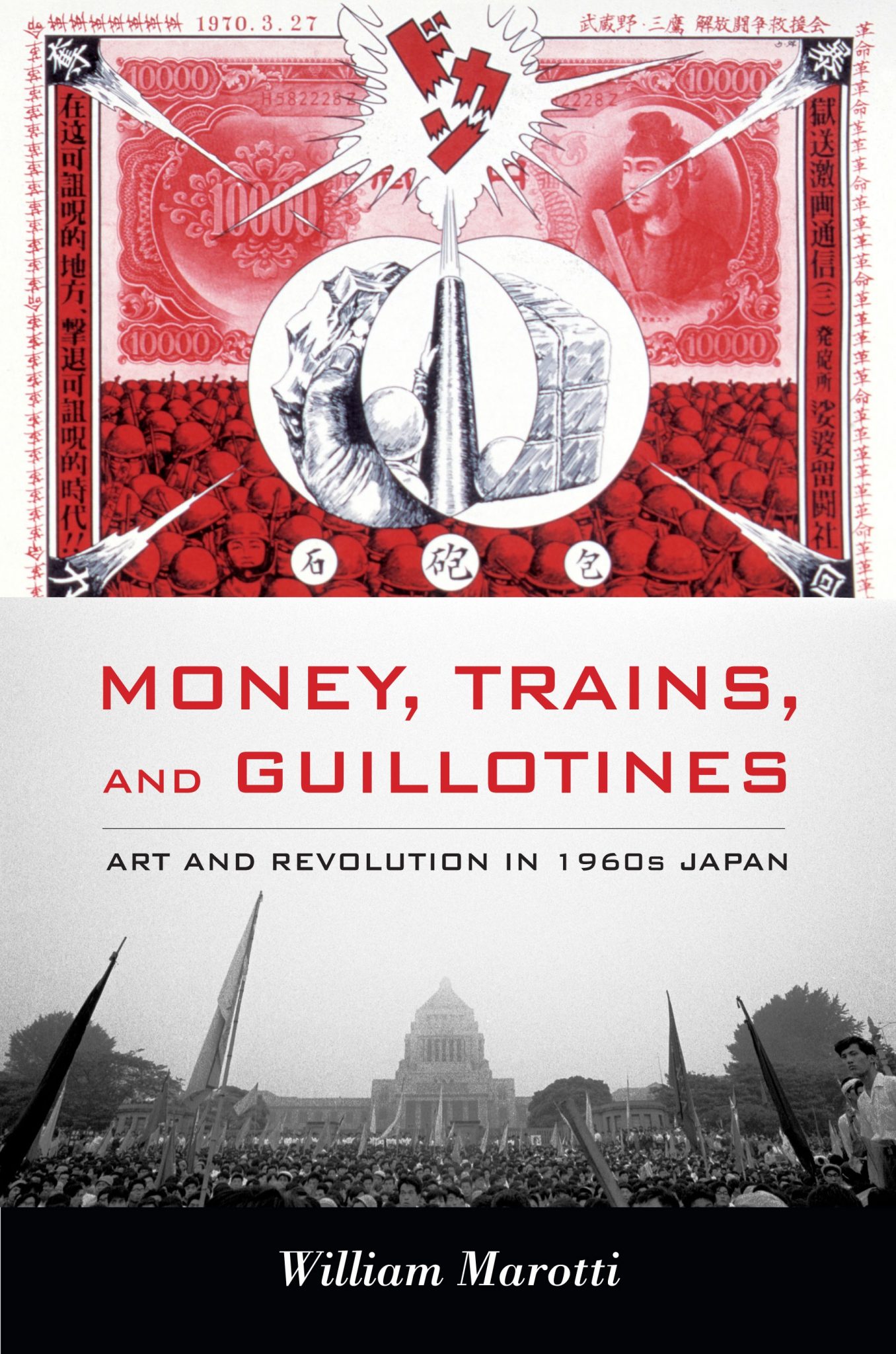

In 1963, the Japanese artist Akasegawa Genpei ordered 300 lifesize prints of the ¥1,000 note, which he then mailed by registered post in envelopes normally used to send cash. On the reverse of each print was an invitation to his one- person show. It was a tease meant to elicit and then disappoint recipients and thus to reveal money as an instrument of assigned and artificial value.

However, this action attracted the attention of the police. Akasegawa was indicted in 1965 and convicted two years later of ‘imitating money’ – a lesser offence than counterfeiting. His appeal to the Supreme Court was rejected in 1971. It is this episode that provides one part of the trinity of objects in the title of William Marotti’s book. The trains reference a neo-dada action staged on a commuter line by associates of Akasegawa; the guillotine a plan to install one near the Imperial Palace in Tokyo.

The 1,000-Yen Note Incident, as it became known, took place at a time of political and artistic crisis in Japan. In 1960, despite mass protests, the government signed the US-Japan Mutual Cooperation and Security Treaty (known as ANPO), reinforcing the impression that the country was an American client state. Four years later, the Yomiuri Indépendant, an open-call exhibition that was the crucial venue for socially critical art at the time, ceased operation because it had become a free-for-all of work its sponsors found aesthetically and socially transgressive. Throughout the period the government attempted to assuage dissent by foregrounding high economic growth and the increasing availability of consumer goods – policies that shaped the comfortable, socially conformist and politically sclerotic nation that is Japan today.

Obsessively tracing and documenting the legal, political and artistic contexts of Akasegawa’s work, Marotti attempts a synthetic analysis of the artist’s thought and of a ‘wider politics of culture in Japan after the Second World War’. He further proposes his study as a demonstration of the kind of thematically based analysis that weaves multiple strands of information into expanding networks of interpretation, in contrast to the reductivist, chronological approach taken in most historical texts.

Marotti convincingly demonstrates how, during the ANPO protests, a small group of artists attracted by the emerging practices of neo-dada and antiart, in which detritus was used as material, became convinced that art must engage with society through direct destabilising acts rather than by remaining a reflection of Japanese consumerism mounted within the context of exhibitions like the Yomiuri Indépendant. Akasegawa’s solution was the ¥1,000 note, which he intended not as a representation of money but as a model of its function. His print was a ‘fake’ simply because it was not assigned a value by government; by mimicking money, he strove to reveal it as a fiction, nothing more than a store of socially mandated value.

From the legal side, this work challenged ‘the state’s duty to interpret – and correct “commonly held social ideas”… in the interest of social hygiene’, an understanding the author bases on the theories of the French philosopher Jacques Rancière. But Marotti never makes clear who the state was or why its agents decided to prosecute Akasegawa: the police officers who first questioned him about the prints showed no interest in pursuing the matter. Nor does Marotti explain how far artists like Akasegawa intended their actions to go. Nakanishi Natsuyuki, who participated in a neo-dada action on a commuter train, bolted in panic during the performance. Rather, Marotti engages in Talmud-like exegeses on, among other things, the possible significance to Nakanishi of the station from which he fled, the medieval prince depicted on the ¥1,000 note, and the role of the emperor in the prewar and postwar constitutions, stringing associations together in dizzying and confusing strands linked by phrases like ‘might be read as’ or ‘could suggest that’. His efforts at parsing his subjects become an attempt to dot every ‘i’ and cross every ‘t’. Ironically, given his argument that Akasegawa resisted categories like ‘art’ and ‘counterfeit’, terms used – according to Rancière – by the state to police social and political norms, Marotti tries to determine the possible meaning of seemingly everything tangentially associated with the artist’s work, returning it to precisely the state that Akasegawa intended to subvert.

This article was first published in the May 2013 issue.