Boom Boom Bang at K.L. Ilham Gallery, Kuala Lumpur celebrates a time in which an extremely fertile urban counterculture movement was born

Few words can characterise Malaysia’s roaring 1990s better than the onomatopoeic ‘boom’ and ‘bang’. It was a decade of moneymaking, of investing and expanding. The nation’s capital housed the tallest buildings in the world, the Petronas Towers, and Malaysia was swiftly transformed into an industrialised country. But such enthusiasm, along with the spending spree, was halted in its tracks by the 1997 Asian financial crisis, which started a chain of events that led to the establishment of the opposition Reformasi political movement (which demanded the resignation of the then prime minister, as well as for more general social equality and justice). It was a time in which an extremely fertile urban counterculture movement was born.

This group exhibition, on show in Kuala Lumpur’s central business district, features 20 artists and collectives who were working at the time, and includes sculptures, installations, textile works, paintings, prints, videos and archival materials such as music tapes and zines from the decade. A 1998 documentary about artists and writers living in Kuala Lumpur during the late 1990s, by Berlin-based filmmakers Zakiah Omar and Hanno Baethe, from which Boom Boom Bang takes its name, plays in a screening room within the exhibition. The film features performing artists and writers who reflect candidly about the money-first approach of the era (“What if we don’t care about becoming rich?” asks one of the interviewees). The film, rarely viewable, is reason enough to visit the exhibition, but there is plenty on display that brings us back to what the country was going through during those fast-paced years, and highlights the irony and inventiveness of those who begged to differ from a government narrative that promoted industrialisation above everything else.

The exhibition opens with a red-carpeted corridor where one is greeted by the installation Pasti Boleh / Sure Can One (1997), by Liew Kung Yu, which pokes fun at governmental ambitions to become one of the ‘Asian Tigers’ (as the ‘miracle economies’ of Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan were described from the 1960s to the 90s). Five encased sculptures collage together photography and bright plastics to create gaudy, angular maquettes that superimpose elements of some of the most iconic development projects of the time, from the Petronas Towers and golf courses to the Kuala Lumpur Tower (completed in 1994), which the artist decomposes to the point of near abstraction. The plexiglass boxes, wrapped up in fancy ribbons like improbably kitsch presents, line both sides of a red carpet leading to a larger sculpture. This flattened figure looks like a mechanical monster in high heels, holding a replica of the Petronas Towers in its right hand. Its body is a collage of countless small parts of plastic scraps, toys and pictures of national and international logos and symbols of consumer culture, from McDonald’s to Mickey Mouse, all ringed in garish multicoloured lights – pointing to the cultural displacement felt as the country was flooded with globalised commodities and corporate signs.

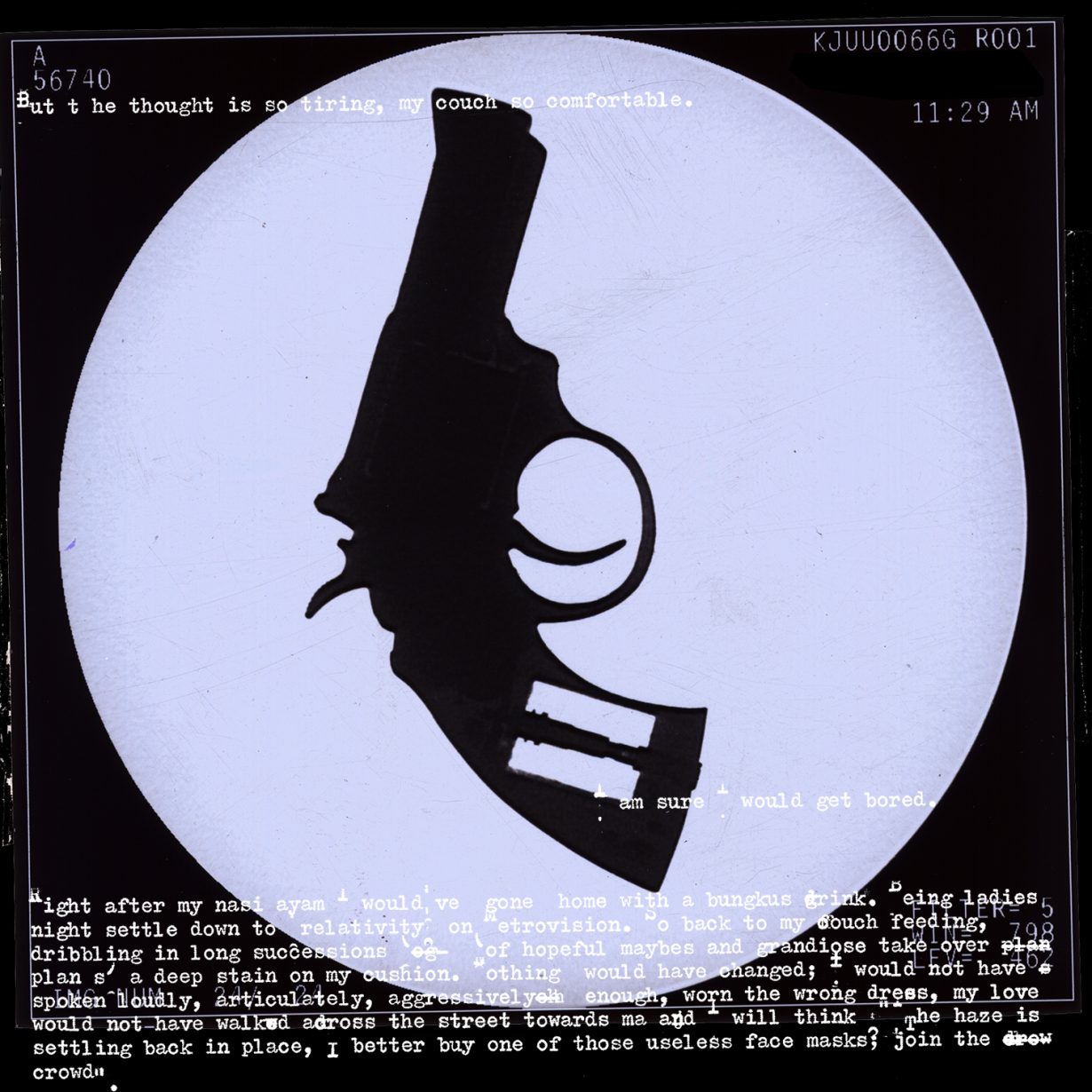

Also on show are some remarkable early printworks by Yee I-Lann, from her series Apathy (1997). Having returned to Malaysia after studying in Australia and Europe, she was learning to navigate Kuala Lumpur just as it was undergoing dramatic political upheavals. These four large varnish-coated paper prints are superimpositions of disjointed words and images that transmit a sense of disillusionment and doubt. ‘If somehow someone managed t o clear the sm g, I may possibly be booted (as a first born, a dusty thinker, a v ictim of hire purchase and telemarketing) into a motivated sense of responsibility and get off my couch,’ reads Boot, the letters appearing over a transparency of an enlarged combat boot.

As the exhibition’s subtitle implies, play and parody were useful modes of response for many artists working in Malaysia during this decade, epitomised by a number of hilarious videos made by the performance ensemble Instant Café Theatre Company. Those that feature actor, director, writer and activist Jo Kukathas, known for her theatrical impersonations, remain very powerful to this day, thanks to her sharp comedic abilities. There are videos of her character the imaginary Judge Mental Singh Gall: a fierce satire of the trial of then deputy prime minister Anwar Ibrahim, who had been accused by the prime minister of sodomy (outlawed in the country) and taken to prison. In YBeeee (2013), Kukathas plays a fictional government figure who is at the same time the minister of misinformation and the minister of breaking records.

The comparison with today is not always flattering; although Malaysia allows peaceful demonstrations, human-rights groups regularly denounce the ways in which the officials treat organisers and allow details relating to their identity to be shared. Throughout the time of the Reformasi movement, activists and artists were emboldened by the wide popular support they enjoyed, which ushered in a period of relatively open artistic expression. What the exhibition makes clear is that work with such sharp mocking of those in power might not be possible to produce, or be so direct, now. Among the most interesting artefacts on show are a collection of zines that were produced during the movement, photos and recordings from underground concerts, and printed documents from the Artis Pro Activ group, whose acronym plays on the Malay word apa, which means ‘what’. Their symbol, a black question mark on a yellow circle surrounded by a black frame, is still occasionally seen at pro-democracy demonstrations.

Boom Boom Bang: Play & Parody in 1990s K.L. at Ilham Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, 13 October – 9 March

From the Spring 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy